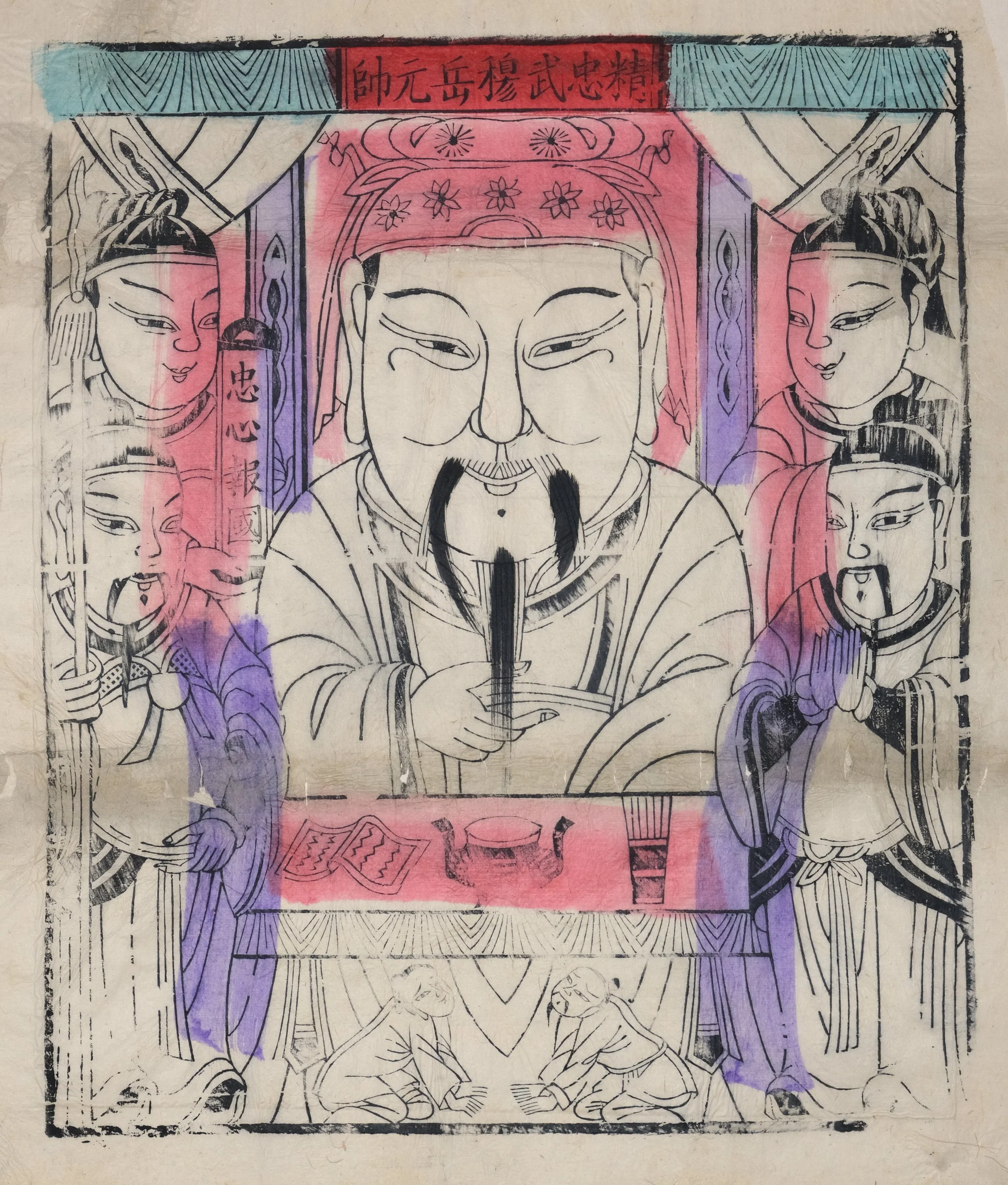

General Yue Fei 精忠武穆岳元帥

Here’s an early twentieth-century zhima devotional print from Beijing. The nameplate reads 精忠武穆岳元帥, “Sincere and Loyal Marshal Yue Fei, titled Wumu”.

Print of Yue Fei, Beijing, 19C

Yue Fei (1103–1142) lived at a time when China’s Song dynasty was battling determined invasions from the north by the “barbarian” Jin (Jurchen). Yue was born into a farming family from Tangyin county town, some way north of the original Song capital, Kaifeng. He joined the army in 1122 and took part in the failed defence of Kaifeng that ended in the humiliating Jingkang Incident of 1127: the Jin breached Kaifeng’s walls and sacked the city, capturing the entire Song court along with the Chinese emperor himself. His brother Gaozong fled south over the Yangzi, eventually re-establishing Song rule at Hangzhou as his armies fought for control of the plains between the Yangzi and Huai rivers.

In 1135 the Jin ruler died and his less bellicose successor approached the Song with a peace offer. This suited Gaozong, who needed time to consolidate his grasp on power (there had already been an attempted coup) – also aware that if his forces actually defeated the Jin, the former emperor might resume the throne. He appointed minister Qin Hui to negotiate.

History does not admire Qin Hui. A career civil servant under the Song, he had been captured when Kaifeng fell but was later mysteriously released and returned to court urging the famously irresolute Gaozong towards appeasement at any cost. Yue Fei, by now commander of the central Yangzi region, represented the opposing military view that Song forces should keep fighting until they had recaptured all of China’s lost territory.

But in 1141 the bureaucrats won: war ended with the Treaty of Shaoxing, the Song agreeing to pay tribute and ceding all lands north of the Huai. Gaozong recalled his military but Yue Fei, poised to retake Kaifeng, initially refused this direct Imperial order. On his eventual return he was imprisoned for treason and died the following year; sources differ as to whether he was assassinated or executed.

Kneeling iron figures of Qin Hui, his wife and cronies in front of the Yue Fei temple at Zhuxian Zhen, Henan

Yet over the following decades, as fighting resumed, Yue Fei became remembered as a symbol of fierce patriotism. Gaozong’s successor Xiaozong granted him a posthumous pardon and the honorary title Wu Mu (武穆), while subsequent emperors named him King of E (鄂王) and Zhongwu (忠武; Loyal Warrior). His fighting skills were passed down too, with both Eagle Claw and Xingyi systems claiming Yue Fei as their founder. Meanwhile, kneeling statues of Qin Hui and other ministers believed complicit in Yue Fei’s downfall were set up in front of his tomb at Hangzhou to be publicly spat at and urinated on by visitors.

The most reliable Yue Fei biography was written by his grandson Yue Ke (岳柯: 鄂國金佗稡編), but it was the later Complete Biography of Yue Fei by Qian Cai (錢彩: 説岳全傳) which everyone remembers. Cobbled together from folklore and the author’s imagination it tells how Yue Fei was rescued from a flood as an infant, how his mother had a loyalty oath tattooed across his back, how he studied martial arts under the foremost teachers of his day and won brilliant campaigns against the Jin, and how the scheming chancellor Qin Hui plotted his recall and had him strangled in prison.

Episodes from the life of Yue Fei by the Yixingcheng Print Studio, Wuqiang (武強義興成畫店)

So back to the devotional image up top. Often these deity prints are generic and only the nameplate can tell you who they represent, but this design is specific to Yue Fei. The rear left attendant holds a tablet with one version of his tattoo, 忠心報國, “Serve the Nation with Loyalty” (some sources say it read 盡忠報國, “Serve the Nation with the Utmost Loyalty”). On the table, an open book touches on Yue Fei’s reputation as a poet, while the two figures kneeling humbly below are the villains of the story, Qin Hui and his wife.

As a symbol of resistance against foreign invaders, Yue Fei fell out of favour during the Manchu-run Qing dynasty (1644–1911) – the Manchus were descendants of the Jin, and themselves had conquered China in 1644. Qian Cai’s Complete Biography was banned and Yue Fei’s cult discouraged in favour of Guan Yu, deity of Martial Righteousness. Guan was similarly noble and loyal (he also died for refusing to betray his state) but his story carried no anti-foreigner overtones.

Yue Fei winning over the ferocious bandit Yang Zaixing at Nine Dragons Mountain. Print from Zhuxian Zhen, Henan, where Yue Fei campaigned in 1140

During China’s early twentieth-century Republican era, Yue Fei’s status rose once again. His tomb complex was renovated, and according to Beiping Customs and Symbols by Li Jiarui (李家瑞; 北平風俗类征) there was a shrine to Yue Fei at Beijing’s Dongyue temple where worshippers prayed for swift retribution against anyone who had wronged them (with a statue of Qin Hui outside for people to abuse). Deity researcher Anne Goodrich reported supplicants would also burn incense in front of his image and ask Yue Fei to settle minor disputes between them. The devotional print above most likely served the same purposes.

Today there are a scattering of Yue Fei temples in Mainland China and Taiwan, sometimes combined with those of Guan Yu.

Many thanks to Laszlo Montgomery, Jimm Wong Pui Fatt, Jim McClanahan, Julian Dale and Christer von der Burg

Sources

China History Podcast Episode 95, General Yue Fei: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cLmxtWKMTZ0

Goodrich, Anne The God of the Eastern Peak (Routledge 2019)

Li Jiarui Beijing Customs and Symbols (北平風俗类征 1937); pdf downloaded from Wikimedia Commons

Lin Jinyuan A Big Picture Book of Taiwan’s Folk Deity Beliefs (台灣民間信仰神明大圖鑑, Jinyuan Book Company, 2005)

Qian Cai General Yue Fei (translation of 説岳全傳, Joint Publishing Hong Kong, 1995)