Hallock’s Gods

It’s unusual to be able to date old Chinese woodblock prints – the same designs were often used for decades, and the cheap paper that they’re printed on ages badly. However, I know that the prints below all date to the around 1930, thanks to the Reverend Henry Galloway Comingo Hallock, whose Chinese name was He Xianli (赫显理).

Born on 31 March 1870 at Holidays Cove, West Virginia, he was educated at Princeton Theological Seminary (where he was known as “Happy Hallock”), and in 1896 joined the American Presbyterian Mission at Shanghai. Hallock was to remain in China for over fifty years, installed briefly as a professor and Dean of Theology at Shanghai’s prestigious St John’s University, pioneering Sunday Schools for underprivileged children, serving as pastor of the red-brick Endeavourer’s Church for Eurasians on the corner of Range and Chapoo roads, and publishing all manner of religious works in Chinese – including some 1,812,000 copies of his annual Hallock’s Chinese Almanac.

But none of this singled Hallock out from the hundreds of other Christian missionaries in China at the time, and he would have been forgotten if, in 1905, he hadn’t resigned from his mission. With no church body funding his causes anymore, he looked around for other ways to raise money and became a prolific writer of what today would be condemned as spam mail – enough to get him banned from any social media platform.

Hallock would buy woodblock prints of Chinese deities at the markets in Shanghai, write letters describing their folklore, and then send them to potential donors in the US. The letters always ended with an appeal for funds, claiming these prints were proof that the Chinese worshiped heathen gods and needed converting to Christianity. Hallock did this for decades, and many of the prints and letters survive, creased from being folded to fit inside the distinctively narrow envelopes that he used.

In May 1927 Hallock sent prints of the Daoist patriarch Zhang Daoling riding a plague-displelling tiger to at least four different people in the US, including two of his Princeton contemporaries. These prints were made for duanwu, the fifth of the fifth lunar month and notorious for being the hottest and unhealthiest time of the year, and served as folk remedies against “the five poisons” – the centipede, snake, spider, toad and lizard. The text names Shangqing temple at Longhu Mountain in Jiangxi province, centre of Zhang Daoling’s Tianshi sect; the prints probably weren’t actually made there, just issued under the temple’s seal.

The accompanying letter outlines the complicated relationship that the Chinese have with tigers: in the real world they are a danger to human life, but their strength and ferocity can be harnessed symbolically. Infants traditionally wore tiger hats to protect them from danger and illness, and Hallock wrote that “as one goes along the roads he sees paper tigers pasted over the door, that the evil spirits, seeing the tiger, will flee away to a tigerless house.”

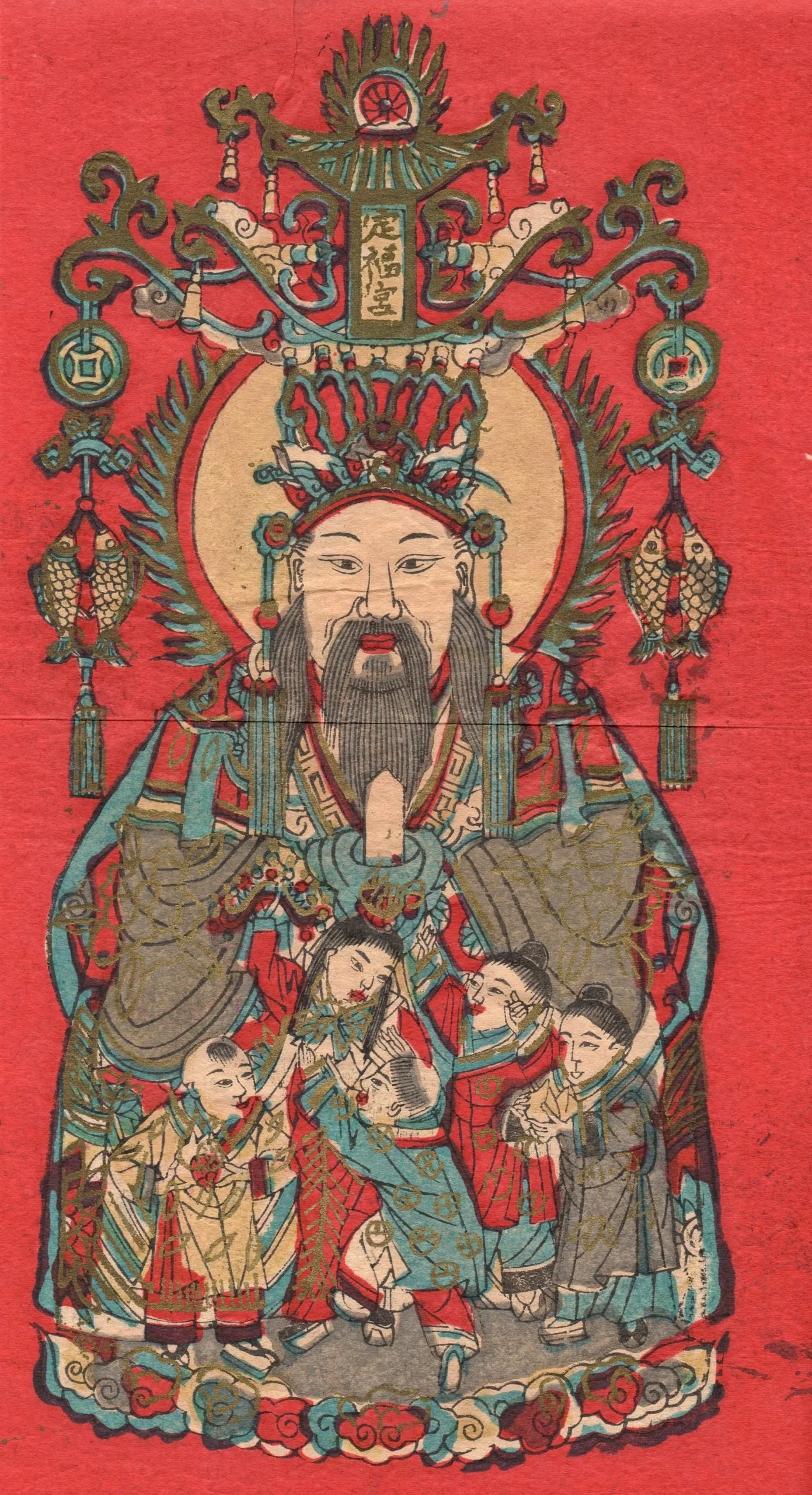

The above print has a well-used design of a central figure surrounded by children which served for many deities. But the tablet reading “Dingfu Palace” identifies this one as the Stove God, Zaojun, patron deity of the household. Pictures of him were pasted up in the kitchen so that Zaojun could watch over the family throughout the year, protecting them from harm. At New Year, he returned to heaven and reported to the Jade Emperor on how the household had behaved over the previous twelve months. The man of the house took down Zaojun’s picture, smeared his lips with honey (either to sweeten his words, or to seal his mouth), and set out water and grass for Zaojun’s horse. The print was then burned to send the god on his way, and a fresh image put up a week later.

Accompanied by a letter dated to September 1927, the third print depicts the red-faced deity of Martial Righteousness, Guan Yu. Guan was a historic general (he died in 220 AD), who together with his oath-brothers Liu Bei and Zhang Fei defended the state of Shu during the break-up of the Han dynasty. The figure behind is his armour-bearer Zhou Cang, a former bandit, holding Guan’s famous “Green Dragon Crescent” halberd – these weapons were later named guan dao, “guan halberds”, in his honour.

Guan Yu’s cult spread widely through China during the nineteenth century, with shrines in just about every temple. His associations with sworn brotherhood made him a patron of both police forces and secret societies, though he’s most widely worshipped today as a wealth deity, representing business profits – his statue often appears in Chinese stores and restaurants.

Pan Gu is central to one of China’s creation myths. Here’s what Hallock has to say about him:

“The male and femal principles, yang and yin, gave birth to Pan-Ku. He had two horns and was a short stubby fellow, but endowed with the ability to grow. He grew six feet every day, and as he lived 18,000 years you can see how big he got. He in some way got possession of an axe, and with that he managed to ‘t’ian di k’ai p’ih’ [天地開辟], hew out the universe. This was seemingly out of nothing or at least out of chaos. He was eighteen thousand years doing the work and to complete it all he had to die. His head is said to have become the mountains; his breath the winds and clouds; his voice the thunder; his limbs the four quarters of the world; his blood the rivers; his flesh the soil; his beard the constellations; his skin and hair the herbs and trees; his teeth, bones and marrow became metal, rocks and precious stones; his sweat the rain; and the insects crawling over his body became human beings.”

“The picture I send shows Pan-Ku and his apron of leaves and his axe. In his hands he holds the sun (red) and the moon. He failed to put them in their proper places and they went away into the sea and the people were left in darkness. A messenger was sent to ask them to go into the sky and give light. They refused. Pan-Ku was called, and at Buddha’s direction wrote the characters ‘ri’ sun, in one hand and ‘yuih’ moon, in the other, and going to the sea he stretched out his hands and called the sun and the moon, repeating a charm devoutly seven times, when they ascended into the sky and gave light day and night.”

“In the creation Pan-Ku made 51 [levels to the universe]. Of these 33 were for heaven and 18 for hell below the earth. The heavens were graded for good men and the floors below the earth were for bad men. If one is the very best of all he can go to the 33rd heaven and be worshipped as a god. If one is very bad he’ll go down to the 18th hell.”

“Even in 18,000 years the work of creation was not completed, but a cavity was left through which many fell to the bottom. After a long time a woman, Nu-Kwa, was born, and she took a stone and blocked up the hole and so finished the work of creation.”

This next print shows the Bodhisattva of Compassion, Guanyin in two simultaneous incarnations: the Bringer of Children, and riding the Aoyu, a fish-like sea monster.

Hallock’s accompanying letter is dated 19 February 1930; Chinese New Year – when the bulk of these woodblock prints were sold – was on 30 January that year. Alternatively, it might have been made for Guanyin’s Birthday on the 19th day of the second lunar month, which would have been mid-March in 1930.

Although the Aoyu aspect represents Guanyin subduing evil in general terms, at Shanghai and coastal eastern China this depiction was also considered to protect seafarers from harm, and replaced the equivalent southern maritime deity, Tian Hou/Mazu.

Guanyin is accompanied by her filial parrot and two child attendants, named Longnu and Shancai; also shown are her vase of water and willow twig sprinkler with which she calms concerns of the world. The “bringer of children” incarnation is emphasised by the locket Guanyin wears round her neck, of the kind widely given to Chinese infants to protect them from harm.

The Chinese text 普門大士 refers to the Universal Gate, the twenty-fifth chapter of the Buddhist Lotus Sutra, which describes the different ways that Guanyin can relieve followers of suffering and guide them towards enlightenment. The other red symbols are protective talismanic charms from popular Chinese religion.