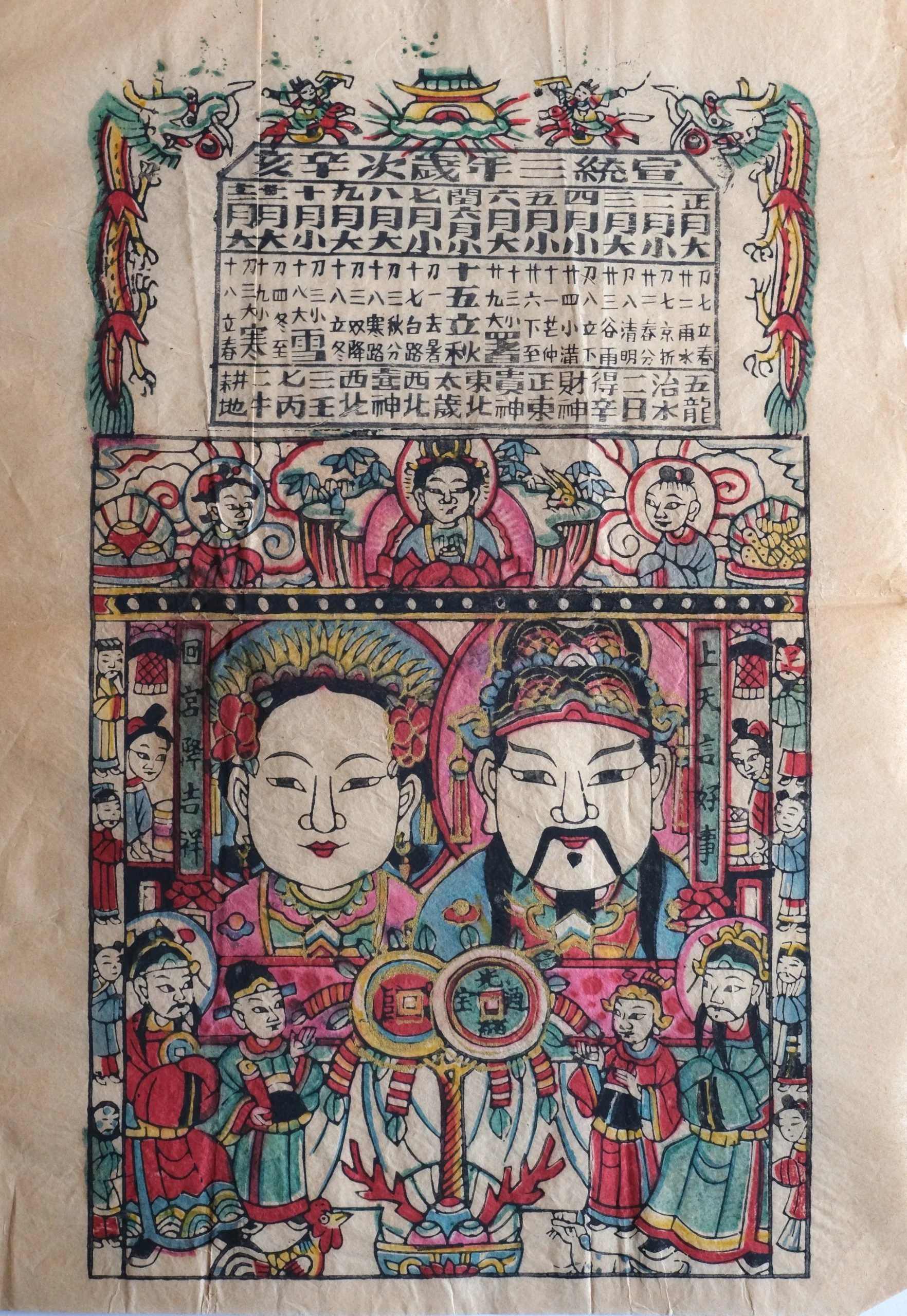

Kitchen God Print for the Xinhai Year 宣統三年歲次辛亥

Here’s a woodblock print of the kitchen god, Zaojun, and his wife. These follow a standard pattern and while a nice, colourful example, there’s nothing remarkable about the illustration.

The small uppermost panel shows Guanyin (note her parrot to the right, her vase to the left), attended by her child acolytes Longnü and Shancai. The gold ingots at the far right, and round boxes to the left side, suggest “wealth” and “harmony”.

Below in the main panel sits the kitchen god and his wife, flanked by couplets reading 上天言好事, 回宮降吉祥. This is a plea for Zaojun to say nice things about the family when he ascends to the Heavenly Palace to make his annual report on their behaviour, thereby bringing the household good fortune for the coming year. Vertical panels next to the couplets show housewives preparing jiaozi and baozi dumplings for a traditional New Year feast.

At the bottom are civil and military officials, lucky coins, a money tree and cornucopia adorned with red coral branches (all broad wishes for prosperity and rank), with a dog and rooster representing safety and security within a household. The Eight Immortals, four stacked vertically each side of the main panel, are protective folk gods.

Chinese woodblock prints are notoriously hard to date – the paper ages quickly and the same designs could be used for decades. Kitchen God prints are useful because they often include a calendar at the top.

And this calendar is is for a very momentous year. The top line reads 宣統三年歲次辛亥, “Xinhai, the Third Year of the Xuantong Reign”.

Xinhai is the forty-eighth year in the sixty-year Chinese calendrical cycle. The Xuantong emperor, better-known as Puyi, came to the throne – aged just two – in late 1908 after the death of his predecessor the Guangxu emperor. So this calendar dates to the third year of Puyi’s reign: 1911.

Puyi, the Xuantong emperor, in 1911

And as it turned out 1911 was the last under China’s 2200-year-old imperial system. On October 10, the innocuous-sounding “Literary Society and Progressive Association” at Wuhan, the huge city on the middle Yangzi now famous for its Covid connections, launched what became known as the Xinhai Revolution against Manchu rule. Within a day Wuhan’s government garrisons had been slaughtered and the city was in rebel hands.

As fighting spread across the country the Imperial court called on Yuan Shikai, head of the powerful Northern Army, to restore order. Yuan brokered Puyi’s abdication and the formation of a Republican government which was sworn in the following year.

Yuan Shikai

But soon Yuan had dismissed the Republican president and taken power for himself, hoping to establish a new Imperial dynasty. It was a bad move: Yuan’s own generals refused to accept him as emperor and on his death in 1916 civil war broke out, which lasted until Mao’s communists took control in 1950.

The Chinese calendar works on six “big” months of 30 days each (大), and six “small” months of 29 days (小) – adding up to 354 days in a year. To make up the shortfall, an extra month was added every three years or so. Calendar buffs might notice that, as shown here in the centre of this calendar, 1911 had a thirteenth, “small”, month.

Calendar with extra, small month vertically at centre of second row: 閏六月小

If there’s anything harder to decide than when a Chinese print was made, it’s where it was made. Although different regions developed very distinctive local styles, at times studios exchanged artists or even stole each other’s designs, so there’s huge overlap. My own feeling – based on style and the colours used – is that this comes from Wuqiang in Hebei. But it’s not in Feng Jicai’s exhaustive catalogue of Wuqiang prints, so either it simply slipped through the net, or it’s from elsewhere.