Magistrate Bao and the Bandwagon Pulps of Shanghai

In a country where corrupt officials were often the norm, Magistrate Bao (包公; 999–1062) stood out for his honest impartiality, condemning to death, beating or imprisoning all criminals, whatever their rank. Folktales and operas depicting his famous cases abounded, and he was later deified as one of the judges in the afterlife.

Episodes from “Three Heroes and Five Gallants”, Wuqiang, Hebei. Magistrate Bao appears twice in the right-hand panel, wearing a black robe trimmed in green

In nineteenth century Beijing, teahouse storyteller Shi Yukun became so renowned for his Magistrate Bao tales that vast crowds packed out venues where he performed; scholars even began attending and writing his versions down. A hugely successful collection of these was published in 1879 as Tales of Loyal Heroes and Righteous Gallants (忠烈俠義傳), reprinted in 1883 as Three Heroes and Five Gallants (三俠五義), then revised in 1889 and given a final literary gloss by a new editor as Seven Heroes and Five Gallants (七俠五義).

Publication of the 1879 version, Tales of Loyal Heroes, coincided with the introduction of metal type to China. Despite being such a conservative country, metal type’s printed clarity and ease of editing saw it immediately preferred over traditional woodblock-printed texts, which were frequently full of errors: many block cutters were illiterate and easily made mistakes with complex Chinese characters, which confusingly had to be cut in reverse so that they would print the right way round. In addition, as blocks wore down characters became illegible, and the woodblock printing process itself – carried out at high speed – often introduced random blots and smears.

Lithographic engravers at the Commercial Press, Shanghai. From “New China and the Printed Page”, National Geographic Magazine, June 1927

Lithography, introduced to China in 1876, offered further advantages: it was cheaper to set up than woodblock printing, and much faster when harnessed to a mechanical press. It also accurately reproduced an individual’s calligraphy, much admired in China as sign of education and moral character. In the 1890s lithographic presses began to hire skilled calligraphers to transcribe China’s vernacular classics for publication, beginning with an illustrated edition of the fourteenth-century Romance of the Three Kingdoms.

The popularity of this version of Three Kingdoms sparked a bookselling boom as publishing houses rushed to get their own editions of the classics out. The industry flourished particularly well in Shanghai, whose European enclave already used modern methods to publish China’s most influential foreign-language paper, the North China Herald, and where a foreign-backed publisher was behind Dianshizhai (1884–1898) China’s first lithographically-printed pictorial.

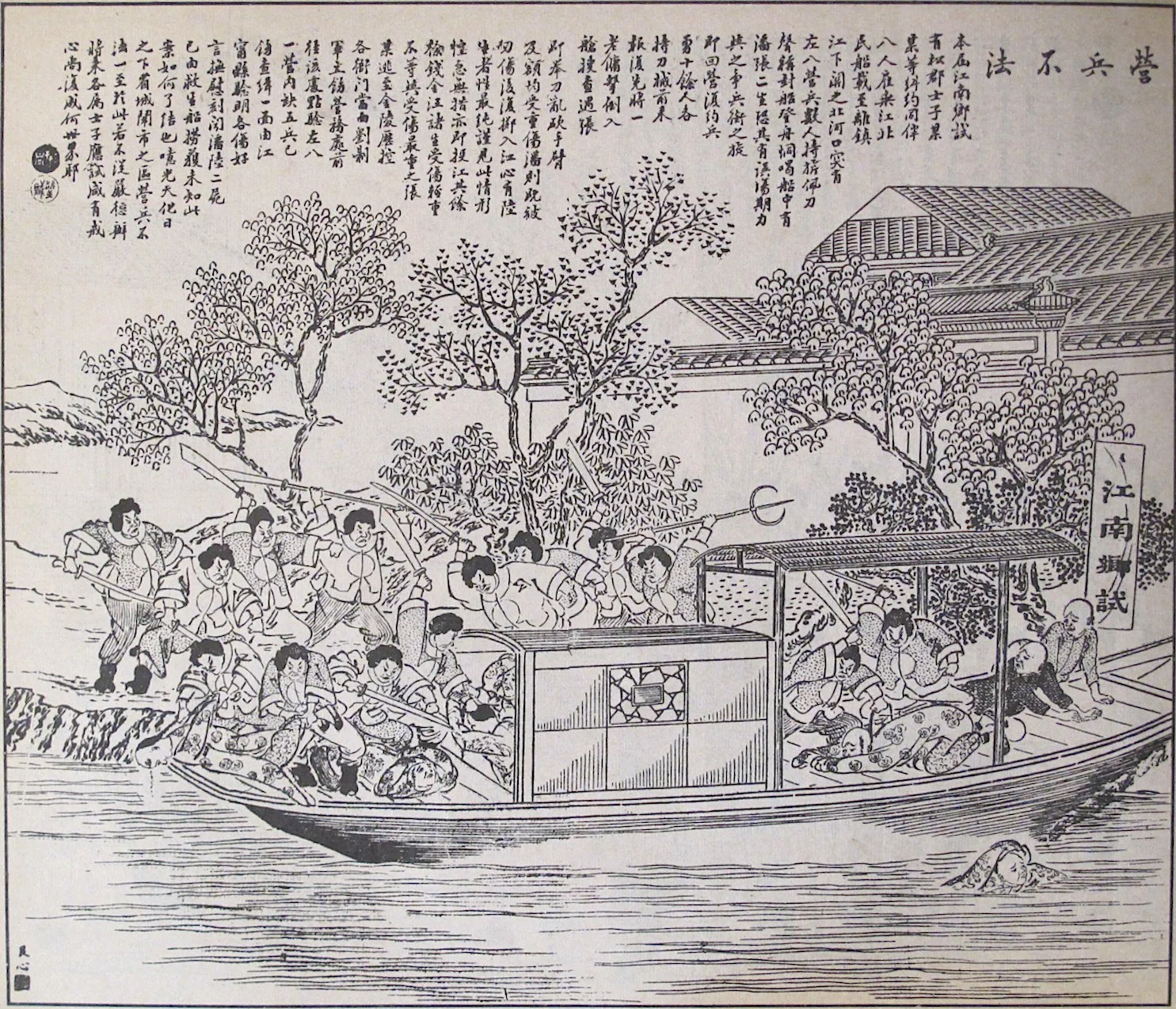

“Soldiers Breaking the Law”. News story from Dianshizhai, date unknown

Eventually though, the market became saturated and publishers ran out of classics. What to do? Well, as with the Marvel Universe, Star Wars and other film franchises, they began commissioning spin-offs, sequels and prequels. Unfortunately – also in line with the modern film industry – most of these new novels fell well short of the originals. As author and literary critic Lu Xun wrote in 1923:

“These stories are repetitious and often written in abominable language, and one character may change personality completely in the course of the book. This was because these works were written by many hands and the editing was carelessly done, resulting in numerous inconsistencies. ... we need not comment on them except to wonder how authors and readers can waste so much time on such trash.”

Two-colour box cover, “Five Swordsmen and Eighteen Gallants; in Big Chinese Characters”. Six volumes with a handwritten inscription inside the case, 購在台山城, 民家書局 1930; “Purchased at Minjia Bookstore, Taishan City, 1930”. First volume title page, “Beautifully Illustrated Prequel to Five Swordsmen and Eighteen Gallants”

And so to the point. I recently bought a set of one of these bandwagon pulps, called Five Swordsmen and Eighteen Gallants (五劍十八義) – a name which clearly hoped to capitalise on the original Magistrate Bao tales. It was brought out in the winter of 1925 by the Shanghai Dacheng Book Publishing Company (上海大成書局發行), who during the early Republican Period released a host of books along the lines of Ten Golden Pills: A Strange Book from the Song Dynasty (粒金丹宋史奇书), Biographies of the Immortals (列仙傳), Liu Yongfu Guards Taiwan (繪圖劉永福鎮守臺灣; based on real events) and a whole library on popular esoteric health practices.

Five Swordsmen comes in an attractive two-colour case; inside are six slim volumes but at 800 characters per page, and 60 pages per volume, that’s still a decent paperback-sized work. The text is pretty small too; the promised “Big Chinese Characters” of the cover means the equivalent of “capitals” rather than “large font”. The first few pages are given over to illustrations of the story’s major players, including His Excellency Xiang, The Iron Rooster, Shi Dakai (one of the leaders of the nineteenth century Taiping Uprising), Monk Puji (a famous real-life cleric from Wutai Shan), the Four-Eyed Dog (another known Taiping leader) and so on.

Opening text and a few of the cast: The “Iron Headed Monk”, Lei Yiming and Zhan Shiming

To be honest, I’m not even sure what this work is called. The name on the box cover is Five Swordsmen and Eighteen Gallants, but the title page of the first volume reads Beautifully Illustrated Prequel to “Five Swordsmen and Eighteen Gallants” (繍像五釼十八義前傳). Prequel or not, I can’t find any other surviving copies, so I guess it fitted into Lu Xun’s “trash” catagory.