Mesny’s Bronze Drum

In 1874, Mesny donated some ethnic artefacts to the Royal Asiatic Society North China Branch at Shanghai, who were talking about opening up a museum. Most of the items were spoils from six years spent fighting Miao and Muslim rebels in Guizhou province, and included a bronze drum:

“Guiyang 3 March 1874

To the President of the R.A.S.

I now send you a Brass Drum, such as the Miao use at their feasts. When I first came here (1868) they were plentiful, nearly every town we took had one or two, but for the last 2 years they have been very scarce, having all been bought up by the Antiquarians of Sichuan and Hunan, who prize them highly. These drums, it is said, were left here by the famous Kong Ming, who invaded Guizhou during the later Han Dynasty, and augmented the population by disbanding part of his “Victorious Army”, amongst whom he distributed the Drums. This one was given me by the gentleman whose card I inclose.”

These drums originated in the China–Vietnam borderlands during the bronze age, perhaps as early as 1000BC, and were cast locally right up to the nineteenth century. They are often called Dong Son drums after the place they were first discovered in the Red River Valley of northern Vietnam, and can be large – more than 60cm across and about the same height, with a narrow waist. There is almost always a picture of a many-pointed star (presumably the sun) in their centre; other typical decorations include long boats with rowers, geometric patterns, birds, and frog figurines around the rim – frogs were the daughters of the thunder god in local mythology.

According to a Ming-dynasty historian, the drums became a symbol of power: “Those who possess bronze drums are chieftains, and the masses obey them; those who have two or three drums can style themselves king.” Cultural exoduses over the last two thousand years has spread their use into Burma, Thailand, Indonesia and Borneo, and as far eastwards as New Guinea. Minority groups through these regions (including the Miao) have continued to use bronze drums into modern times.

Back to Mesny’s drum. In 1888 – fourteen years after his donation – Mesny was writing frustrated letters to the North China Herald complaining that the RAS museum still hadn’t put his artefacts on show. Perhaps he even took the drum back off them in protest; certainly there are no documents or photographs to prove that it was ever exhibited. Most of the RAS collection survived the twentieth century’s many upheavals and was later absorbed into the current Shanghai Museum. But I thought Mesny’s drum had been lost, until a friend pointed out this entry from 1895 in Mesny’s Chinese Miscellany (mostly copied from a Chinese ethnographic work, 百苗图, Descriptions of 100 Miao Tribes):

“1594: P’U-LUNG CH’UNG CHIA 普籠狆家: A tribe of Miao-tzu inhabiting parts of Anshun Fu prefecture, especially in the country of Pu-ting Hsien, in the neighbourhood of the prefectural city. They are also met with as settlers in parts of Ting-fan Zhou and Kuang-shun Chou. They are revengeful people, swift to anger. They are said to be exceptionally fond of shrimps and fish, and use them as sacrificial offerings. At their great feast on the 1st day of the 12th moon they rejoice and beat brass drums called T’ung-ku 铜鼓, one of which I presented to H.I.M. [His Imperial Majesty] the emperor of Austria some years ago, and another I still have.”

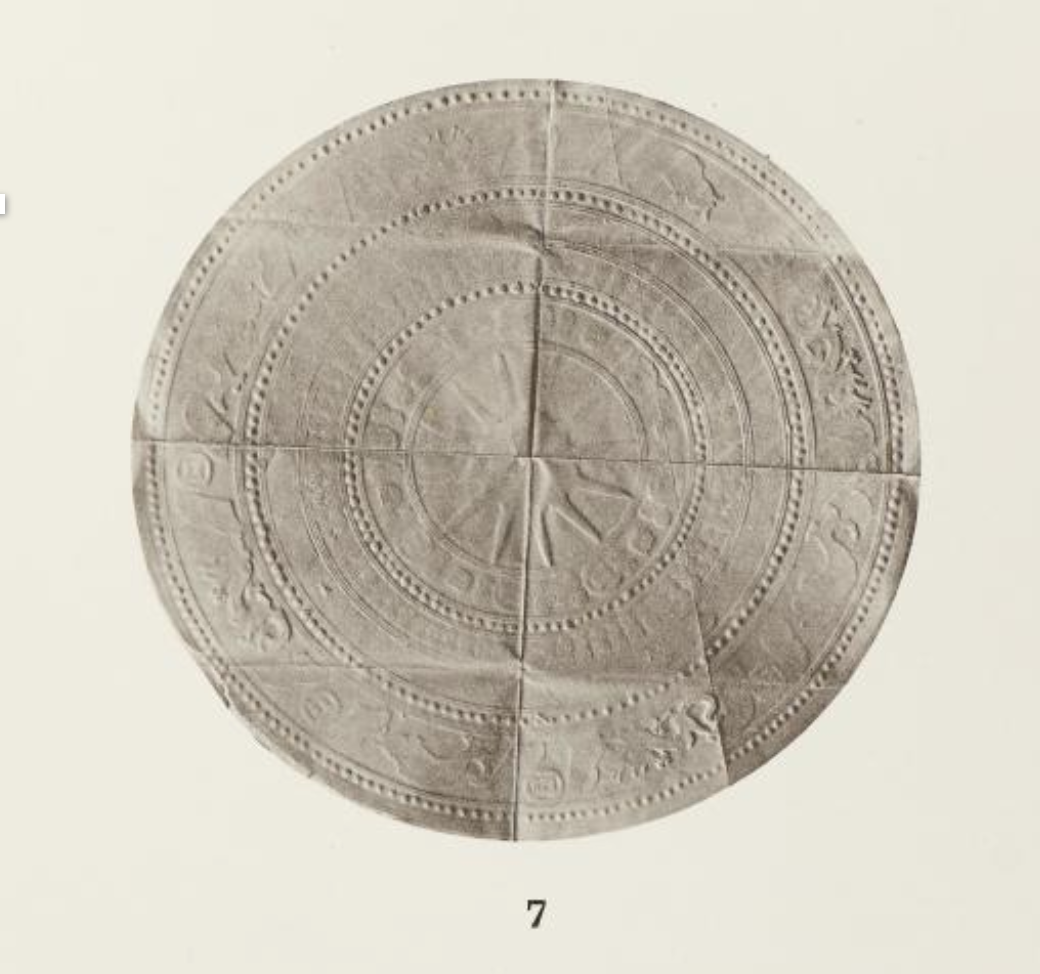

Mesny’s claim to have presented the drum to the emperor of Austria is a bit of a stretch: he either gave or sold it in 1885 to the Austrian Consul at Shanghai, Josef von Haas, who donated it to the Hofmuseum at Vienna. It was described in their catalogue as weighing 13.7kg and measuring 48cm across; a rubbing of the tympanum was also illustrated in the book Bronzepauken aus Südost-Asien (Bronze Drums of Southeast Asia, 1897) by Adolf Meyer and William Foy.

And, following a bit of a paper-chase, I finally traced Mesny’s actual drum to the storage vaults of Vienna’s Weltsmuseum, whose staff sent the top photo above.

Thanks to Dow Yu in Guizhou for pointing out the Austrian connection. In Vienna, many thanks to Ingrid Viehberger of the Naturhistorisches Museum, and Natascha Strassl and Dr Bettina Zorn of the Weltsmuseum.