Two Door Gods from Fengxiang

Here are a pair of door gods from Fengxiang (鳳翔), a small grid of a town town about 150km west of Xi’an in Shaanxi province. This was once a major stop on the trunk road to Xinjiang, but the growth of Baoji city – an enormous sprawling modern industrial centre to the south – has seen it slip into semi-rural status. Fragments of the old city wall are incorporated into parks on the west and east sides of town, and there’s plenty of small-scale street life to soak up.

Pale-faced Qin Qiong aka Shubao (d.638 AD), and fiercely-bearded Yuchi Gong, aka Jingde (585-658 AD)

Catalogues name these two as the well-known pair Qin Qiong and Yuchi Gong, real-life generals who served the seventh-century Tang emperor Taizong and were later canonised. Oddly they are shown here wearing scholar’s robes instead of their usual parade armour, though each still carries their trademark sword-breakers.

What makes these two prints special is their size: these are reputedly the largest printed door gods in China at nearly a metre tall, approaching the technical limit for multi-coloured woodblock printing. A good deal of care and skill was also used to ensure that each colour block was registered precisely with the black outline, ensuring the colours ended up exactly where they should – something that Chinese craftsmen often paid little attention to.

Printing table with central slot, pink ink, and palm-fibre rubbing pads

In March 2025 I was in Fengxiang looking for more information, but couldn’t find any. So I wandered into an antique store and asked the owner about woodblock printers. "Hang on, I'll call my friend, he's one... OK, he's waiting to see you." He wrote directions on a scrap of paper. "Here, give this to a taxi and they'll take you there".

Twenty minutes later I was off in the countryside south of town at Nanxiaoli village (南小里), home to Tai Wei (邰伟), sixteenth-generation woodblock printer and inheritor of Fengxiang's last surviving studio, the Shixing Picture Bureau (世興画局). They produced these giant prints, part of a set of eight featuring pairs of civil and military officials.

Tai Wei holding the top half of the Qin Qiong print block. The ring bottom right is a sort of copyright mark

Mr Tai told me that there have been printing workshops at Fengxiang since the 1500s, with about one hundred pumping out millions of prints annually during the late nineteenth-century production peak – comparable with other similarly-sized centres elsewhere in China. By the 1970s, however, faster mechanical processes and political upheavals had closed most of Fengxiang’s studios.

Beginning in the late 1970s, Tai Wei’s grandfather Tai Yi (邰怡; 1921–1984) and his son Tai Liping (邰立平; born 1952) resurrected the local industry, making new designs and also recutting blocks for traditional prints which survived the turbulent 1960s. But sales today are just a few thousand a year, bringing in barely enough income to keep the workshop going.

The studio now consists pretty much of one small room lined with cupboards and shelving full of prints and printing blocks. There are just two printing tables, piled with trays of dried ink and palm-fibre rubbing pads. Mr Tai pulled out two blocks used for making the giant door gods, these ones freshly cut and unused.

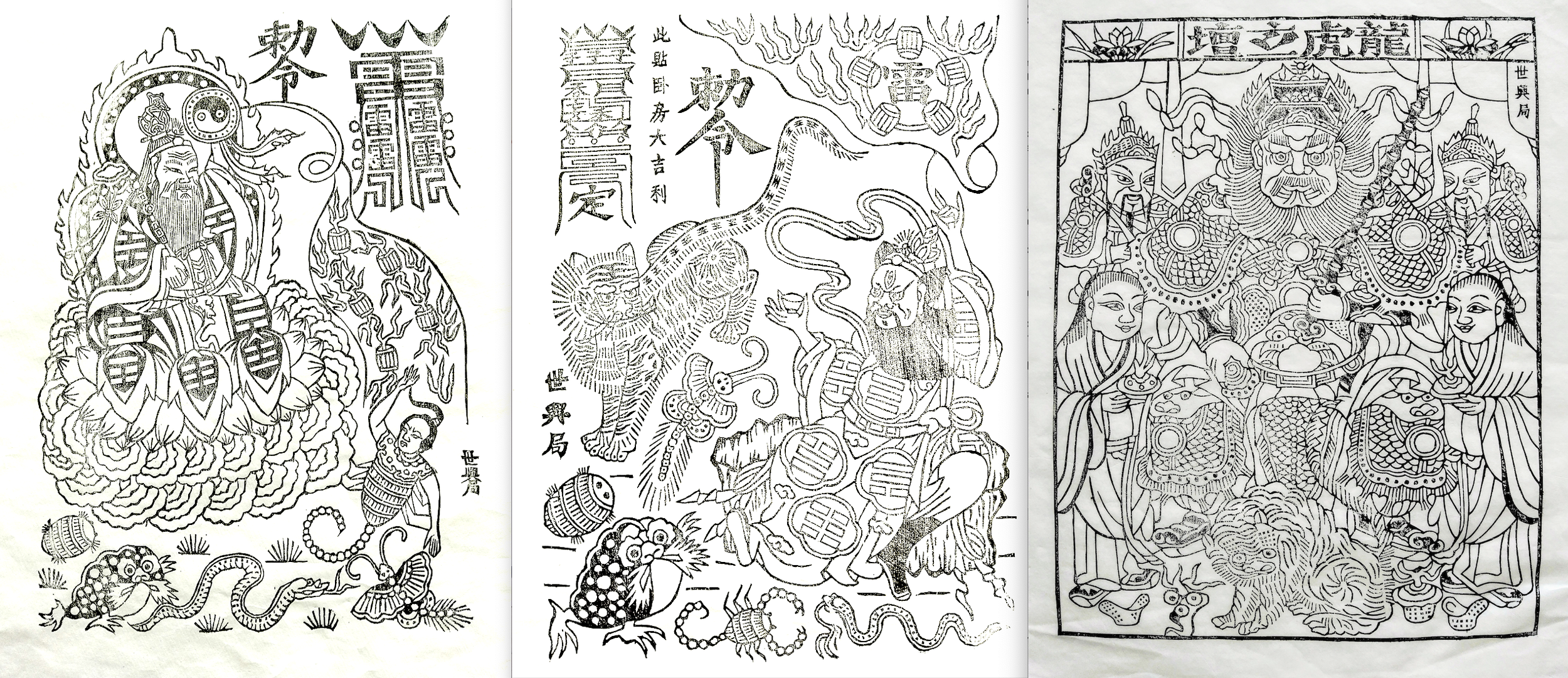

Three deity prints: Laozi (left) and Zhang Daoling with his tiger (centre), both using Five Thunder magic to defeat four “poisons” (snake, scorpion, toad, insect), with possibly Zhang Daoling again at right, master of the Dragon-Tiger Altar (Dragon-Tiger Mountain in Jiangxi province is the centre for his cult). Alternatively it could be Zhao Gongming, the military god of wealth

Most of his other prints were from traditional designs, the most recent dating back a century or so. Many were monochrome deity prints, 紙馬, used to ward off bad fortune; there were also a couple of designs in green, yellow and red featuring local proverbs.

Having answered all my questions, Mr Tai refused to let me call a cab and insisted on driving me back to my hotel. Yes, I did go back and thank the antique dealer. What a nice bunch of people.

Many thanks to Jimm Wong Pui Fatt

Further reading: 中国木版年画集成-凤翔卷