Yamdena

Between 1997 and 1998 I spent six months working in Sulawesi, Kalimantan and Maluku, researching a guidebook to Indonesia. As a region of island groups scattered across 2000km of ocean, just getting around occupied most of my time. In theory, you could fly between major centres, but in practice the planes seldom left the ground, and when they did take off, they had a habit of not arriving. One flight I’d hoped to catch to the Aru islands off New Guinea was grounded after the crew refused to get back on board until essential repairs were carried out. Three months later, the aircraft – fully refitted – took off into the blue, never to be seen again.

So in the end I spent most of those six months on ferries, either chugging up rivers like the Mahakham in Kalimantan or crossing the sea to islands so remote that they were only barely still inside Indonesian waters. In personal terms there were many rewards: I hiked through jungles and scuba-dived to my heart’s content; saw proboscis monkeys, gibbons, tarsiers, black macaque, flying lizards, ecelectus parrots, birds of paradise and green tree pythons; and followed in the footsteps of one of my zoological heroes, Alfred Wallace, who – along with Charles Darwin – worked out the theory of evolution by natural selection. But as far as my job went, concrete sights were few and far between, and it was often impossible to guarantee others much of a return for the effort needed to reach these places.

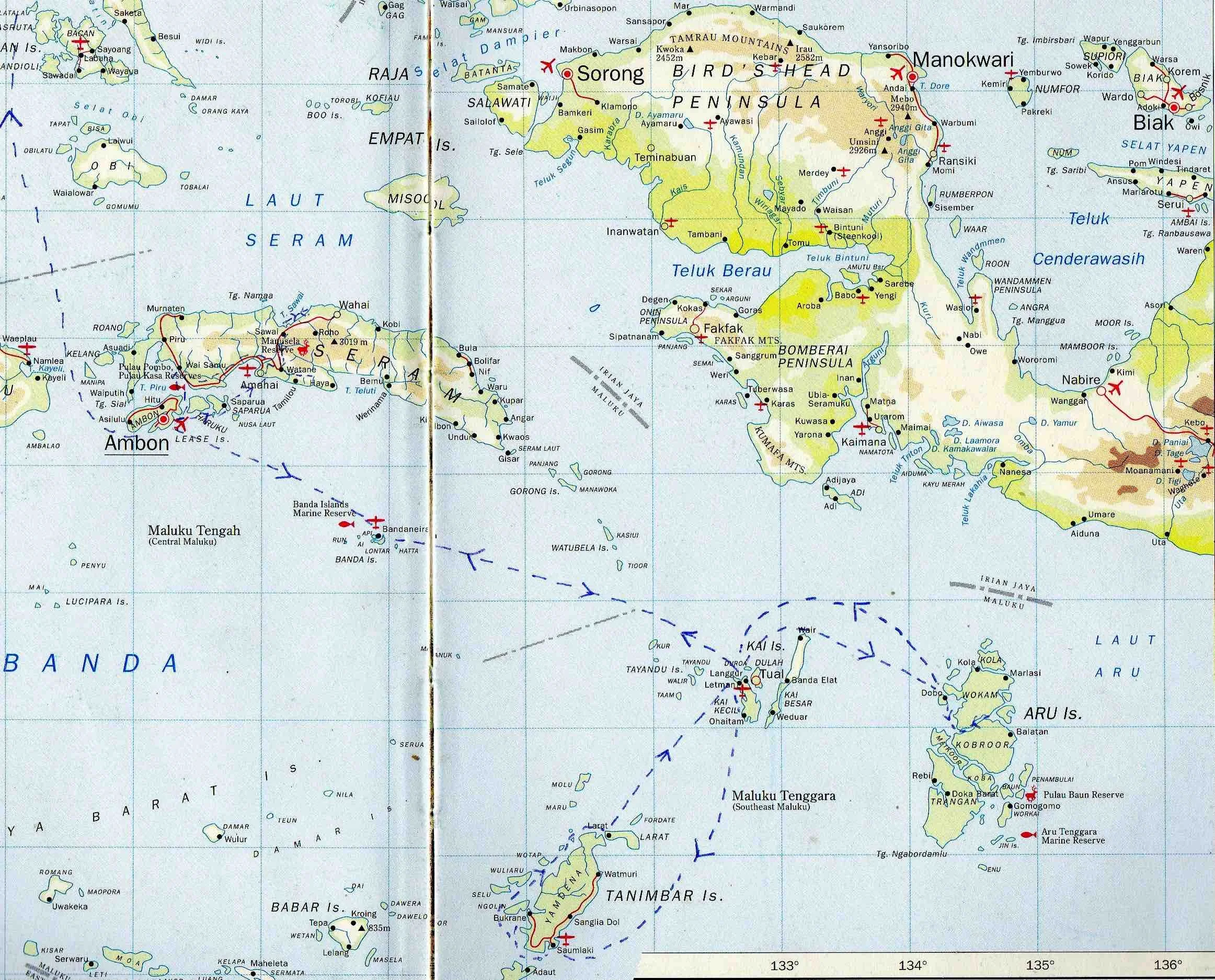

Take Yamdena in the Tanimbars, an island stuck out on the edge of the Arafura Sea between New Guinea and Australia. The advertised weekly flight rarely took off, of course, but there was a reliable passenger ferry via the nearby Kei islands. Unfortunately, after calling in to Yamdena, the ferry continued on a lengthy circuit out of the region, so there was no sure way back to Kei afterwards. We went anyway, counting on hitching an onwards ride aboard one of the cargo ships that plied the region.

Yamdena turned out to be nice enough. The sole town and main port, Saumlaki, was nondescript but provided good accommodation with as much curried vegetables, venison and fresh seafood as we could eat three times a day, people were friendly, and – joy – we got hissed at by a large snake. The centre of Yamdena was covered in near-impenetrable forests, home to ferocious wild cattle, so nobody went there. Villages were scattered up the east coast, connected by a single rough road and surrounded by coconut and banana plantations. Yamdena’s main tourist attraction was its stone boats, full-sized replicas of the vessels which had originally brought settlers to the island. Built of flat blocks like a dry-stone wall, they once sat the centre of each village, though now only three were left. The most complete – or accessible, anyway – was at Sangliat Dol, about 30km up the coast from Saumlaki, so we headed there.

As always in Indonesia, approved religion and traditional local beliefs had been melded into a contradictory tangle that didn’t seem to bother anyone at Sangliat Dol very much. Despite a church, whose corrogated iron roof and prominent crossed spire overlooked the village, a visit to the boat required permission from the kepala adat, the “Master of Traditions” and a brief ceremony to placate the ancestral spirits with a mouthful or two of palm wine. The boat was broad, pointed at either end like a long ship, and partly overgrown with weeds; the most interesting part was its horned prow, richly carved with fish and symbolic swirls. It was stolen by antiques thieves a few years later.

Given that their colonist ancestors had been a seafaring people, boats – and not just stone ones – were central to Sangliat Dol’s culture. In fact the entire village was organised as if it was a huge boat, though this wasn’t immediately obvious from the ordinary, grid-like layout of the houses. But where you lived depended on the position that your ancestor had occupied in the real vessel on the voyage over: the captain’s descendant lived at the head of the village, the oarsmen’s houses ran down the sides, the helmsman’s was at the back, and so on. Each clan re-lived their roles during festivals, when members took up their relevant hereditary position on the stone boat.

On another occasion we were at the villiage of Olilit Lama when a man literally leaped out of a doorway and asked if we wanted to see an old sword. Of course we said yes, and he ushered us in to his house. Once past a workshop crammed with half-finished furniture – he was a carpenter – we were shown in to the front room, offered coffee, and introduced to his wife and teenage daughters. Our host went off to some back room to unearth his sword, leaving us sitting on a sofa, idly staring about and taking in the barely-furnished room. A crucifix hung on one wall, under which a human skull sat blandly on a book case, a cloth draped over what turned out to be a gaping hole in the cranium. Back came our host with a rusty piece of metal which might have been the remains of a sword, or perhaps a random piece of a car wreck. We steered the conversation around to the skull. “Oh, that’s my grandmother. She looks after us. Do you smoke? No, foreigners never smoke. I have to smoke. If I don’t smoke, I fall asleep. If I fall asleep, I can’t work. Do you have a camera? Take my photograph!” He took us back into the workshop, pulled out a tin and brush and began varnishing a tabletop. “Done? Good. OK, bye”.

We did manage to leave Yamdena eventually. Between filling in time on side trips out to nearby islets to look for rare orchids, our daily routine included a stop at Saumlaki’s harbour to ask for news of cargo boats willing to take passengers. As the days passed, the number of other people hoping to hitch a ride out grew and grew, and when a vessel finally did dock it was immediately swamped by an eager throng to the point that it almost sank at its mooring, with barely even standing room left on deck. I’ve done many dangerous things in my life – including hitching a truck ride up through Kenya to the Somali border on top of a shipment of glass bottles – but this looked worse. We decided to wait for another ride.

Incredibly, given how long we had waited for a vessel, another turned up within an hour of the first ship’s departure. True, it was a live goat transport, but by now there were only a handful of passengers left at the dock who, like us, had been unwilling to leave earlier. We had as much deck space as we needed to roll out straw mats and kick back on for the duration, there was an awning to protect us from the sun, and they fed us boiled rice and fried fish three times a day. With a calm sea around us, it was a good way to spend twenty-four hours.