Zhang Xiumei and the Miao War

The Miao Uprising in Guizhou (1855–1873) was – cutting out all the fiddly details – a rebellion against the Chinese administration by the majority Hmong (Miao) ethnic minority. The Miao are concentrated in Qiandongnan, southeastern Guizhou province, a mountainous region where the only Chinese presence was in a handful of trading posts and garrison towns guarding the lowland roads. Once these had been overrun, the Miao controlled Qiandongnan for most of the uprising, and it was only around 1868 – after Chinese armies elsewhere had been freed up by the end of the Taiping Rebellion – that Chinese forces began to make any headway against the rebels.

The uprising began at Taijiang, one of the Chinese-founded garrison towns, in the wake of a famine which had left many locals destitute. According to Historic Poems of the Miao Rebellion, Miao leaders had asked the “dog-hearted” magistrate for tax relief, only to have him draw his sword and threaten to execute the lot of them unless their taxes were paid in full. So a call to war went out and all the chieftains gathered: Yang Daliu from Langde, Pang Laomo with his rebel Chinese followers, Guan Baoniu from Zhaitou, Zhang Xiumei from Bandeng, Zhu Song from Furong village and the woman warrior E-Jiao from Huangpiao. They drank buffalo blood mixed with wine and swore to drive the Chinese from their lands.

The modern version of events is that Zhang Xiumei (1823–1872), a native of Taijiang, became overall leader of the rebellion – though few contemporary sources (including Mesny) mention him. At any rate, he’s held to have taken part in the ambush at Huangpiao that almost destroyed the Hunan Army, and the last major campaign of the war at Wuyapo, when the Miao forces were finally crushed. Along with other Miao warlords, Zhang was captured at Wuyapo and taken to Changsha in Hunan province, where he was executed.

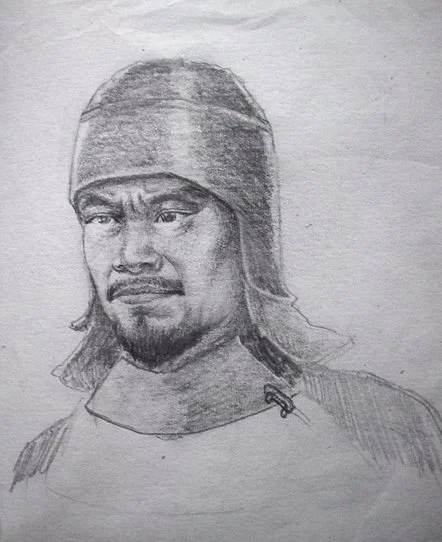

Today, Zhang’s leadership is commemorated by this huge granite statue of him in Taijiang’s public square. They were having a festival for him when I took the photo above, with votive candles and free food and rice wine. Zhang’s face was modelled on this artist’s impression, based on contemporary descriptions and a strong family resemblance in his descendants:

But the breastplate and studded belt are wrong; Zhang wore a home-made helmet and suit of banded armour, still preserved in the bowels of Guiyang’s provincial museum.

Zhang’s home village, Bandeng, sits high up in the hills west of Taijiang, a good four-hour hike along muddy country roads past wallowing water buffalos, scattered hamlets of timber houses, old trees hung with red ribbons and roadside family tombs. I visited in 2012 with my Miao friend, Li Maoqing, while researching the Mercenary Mandarin.

We rested up at a villager’s home, whose owner welcomed us with cold water and sour vegetable hotpot; I hope I can one day be as hospitable to complete strangers turning up unannounced. He told us how, after the final battle at Wuyapo, the Chinese rampaged through the countryside burning down every settlement they could find and killing everyone who couldn’t run away. Members of his own family had been slaughtered at this very house, and Bandeng virtually destroyed. Zhang Xiumei’s wife escaped, however, along with their son, Je.

After Zhang’s execution, somebody bravely stole back his head and returned it to Bandeng for proper burial, and his recently-restored tomb stands at the edge of the village, a small grassy mound ringed in grey brick, with the Chinese characters for “Zhang Xiumei” picked out in crimson on a headstone.

The view down off the mountain from here is fabulous, the steep rice terraces and a succession of forested ridges dropping into hidden valleys, all blued by the distance. A good spot to spend eternity.