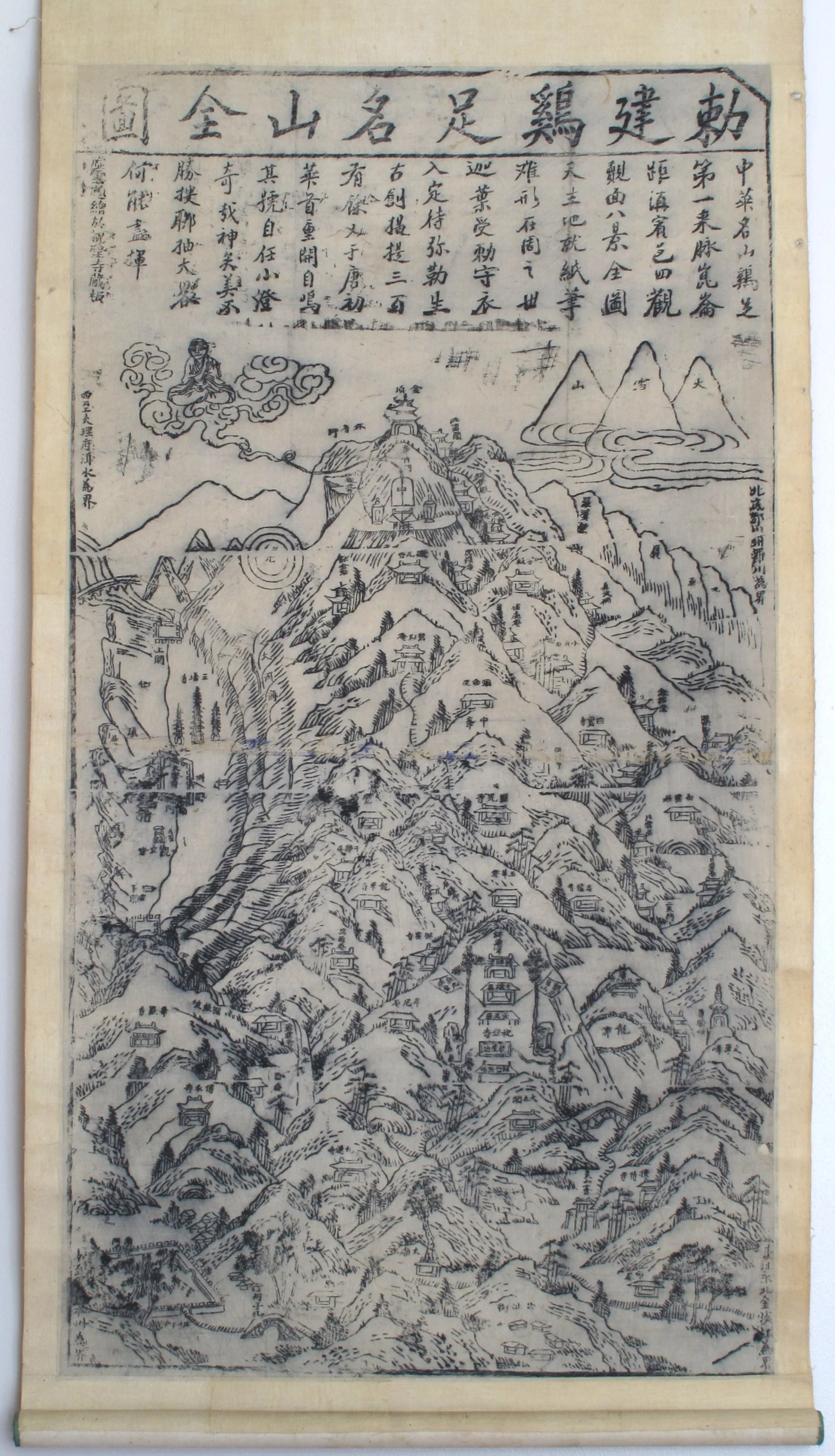

A Complete Picture of the Imperially Sanctioned Famous Mountain, Jizu Shan: 勅建雞足名山全圖

Here’s a woodblock-printed map of Yunnan province’s Jizu Shan (雞足山) – Chickenfoot Mountain – which peaks at 3240m east of Erhai Lake and the old walled town of Dali. The modern explanation is that Jizu Shan got its name because “it is formed with three ridges in front and one at the back, exactly like the four toes of a chicken’s foot”.

Reasonable enough, but not exactly true. Jizu Shan was once called Jiuqu Shan (九曲山), Nine-turns Mountain, perhaps because of the dangerous, twisting path to the top; the artist Huang Xiangjian, who painted a colour landscape scroll of the mountain in 1656, had to scramble the final kilometre to the summit on his hands and knees, up the steep, cracked steps of the“Monkey Staircase”.

The Monkey Staircase to Jizu Shan’s summit, from the scroll “Searching for My Parents; Mount Jizu” by Huang Xiangjian

But the current name has Buddhist origins. The mountain has been a religious site since the third century, once considered China’s “Fifth Great Buddhist Peak” (after Wutai, Emei, Putuo and Jiuhua mountains), with over seventy temples, hundreds of monasteries and shrines, and a vast community of monks.

Part of its popularity was because the mountain had become identified with the story of Kasyapa, one of Buddha’s disciples. In the original version, set in India, Kasyapa had entombed himself for five billion years inside Kukkutapadagiri (“Chickenfoot Mountain”), awaiting the coming of the Future Buddha, Maitreya. At some point, Jiuqu Shan’s monks adopted the story, transferred the setting from India to their own mountain, and renamed it Jizu Shan, the Chinese translation of Kukkutapadagiri.

Jizu Shan remains important to three streams of Buddhism: the locally dominant Pureland sect; Tibetan (outrunners of the Himalayas can be seen from the mountain’s summit); and Zen (Chan), through the twentieth-century master Xu Yun, who once lived here.

The map

Today Jizu Shan is overrun with tourists, not pilgrims, but this map, measuring 86cm by 46cm, might have been printed for either. According to early twentieth-century Westerners in China, temples on many holy mountains gave “visitors crude maps or plans of the mountain, duly stamped with the monastery seal, as proof that the journey had been made”.

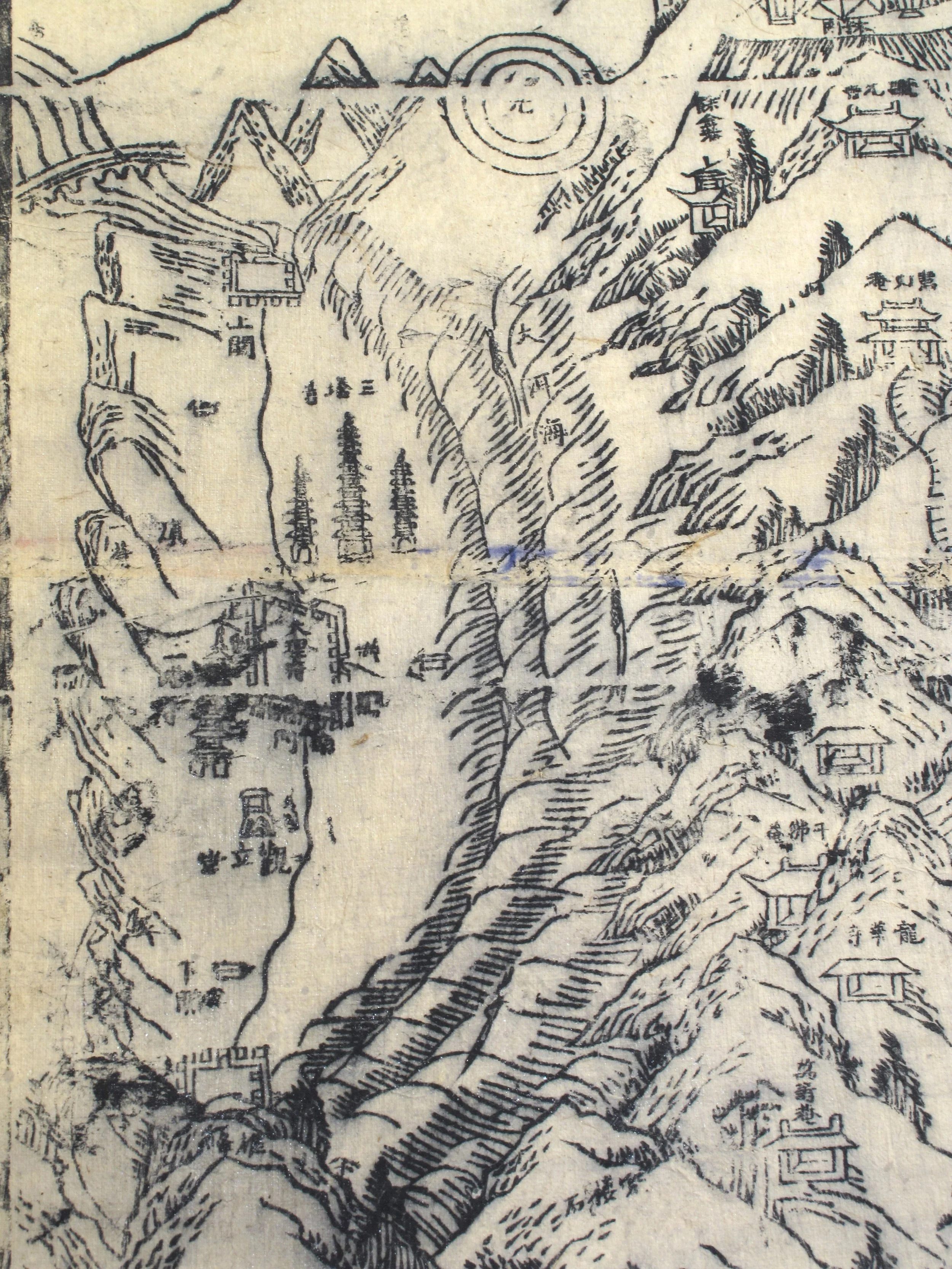

Oriented north-south, this one is fairly accurate, showing the nearest towns, the mountain’s temples and grottoes, and most of the peaks. To the left side of the print is Er Hai Lake, with Dali and its trademark three pagodas (seemingly rising from the water) on the west shore, and Xiaguan at the southern tip.

Crescent-shaped Er Hai at left, with walled towns of Dali halfway up the west shore, and Xiaguan at the south. Dali’s three pagodas should be on land behind the town

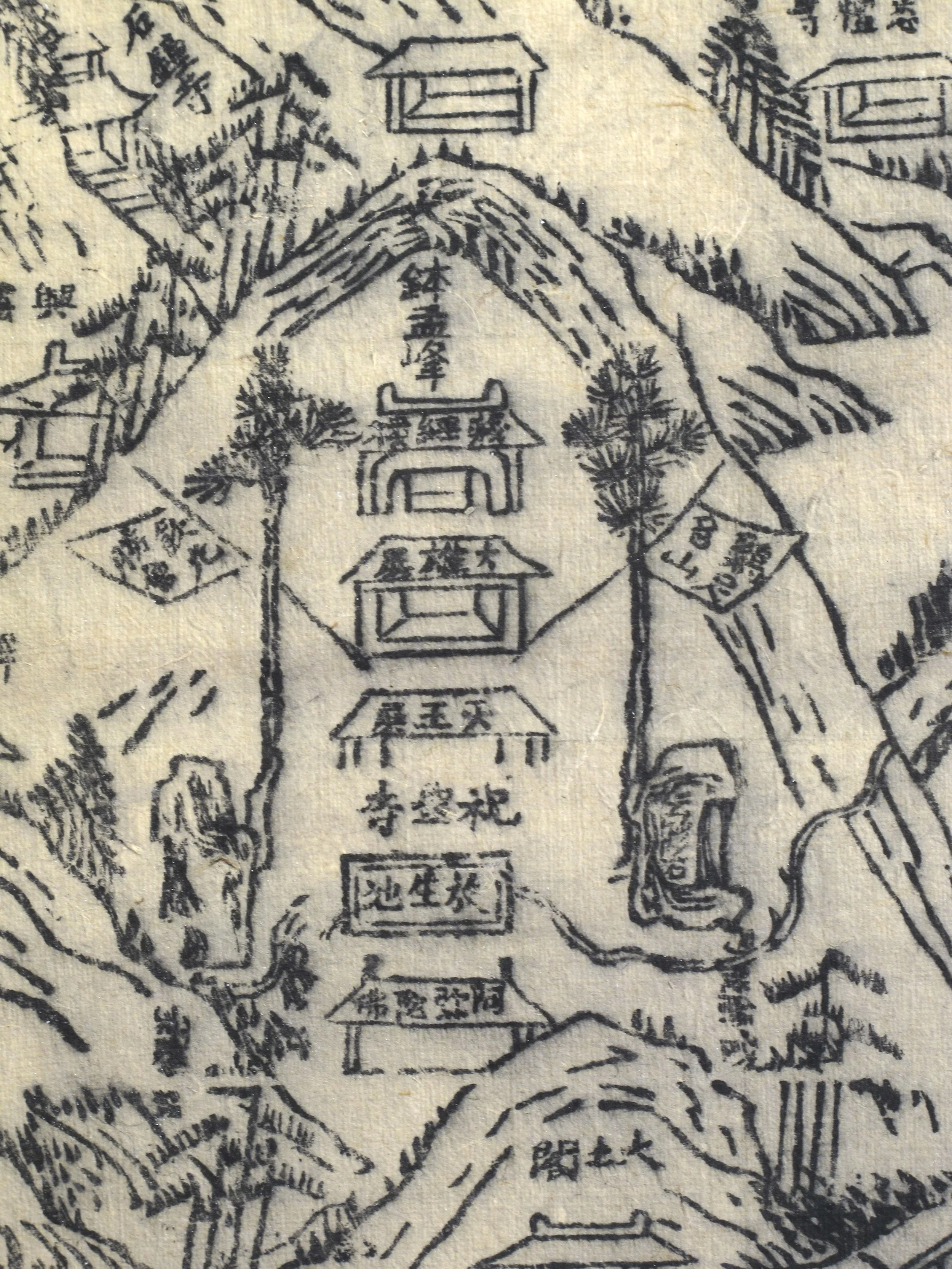

At the lower ower left corner are the walls of Binchuan town, where routes up the mountain begin. Paths head up via bridges, temple complexes, shrines and grottoes to below the summit where, flanked by two stupas, is the carved outline of Huashou Men, the “gateway” into the mountain where Kasyapa is believed to be meditating. One story goes that the sound of a huge bell is said to ring out here at the approach of an enlightened pilgrim.

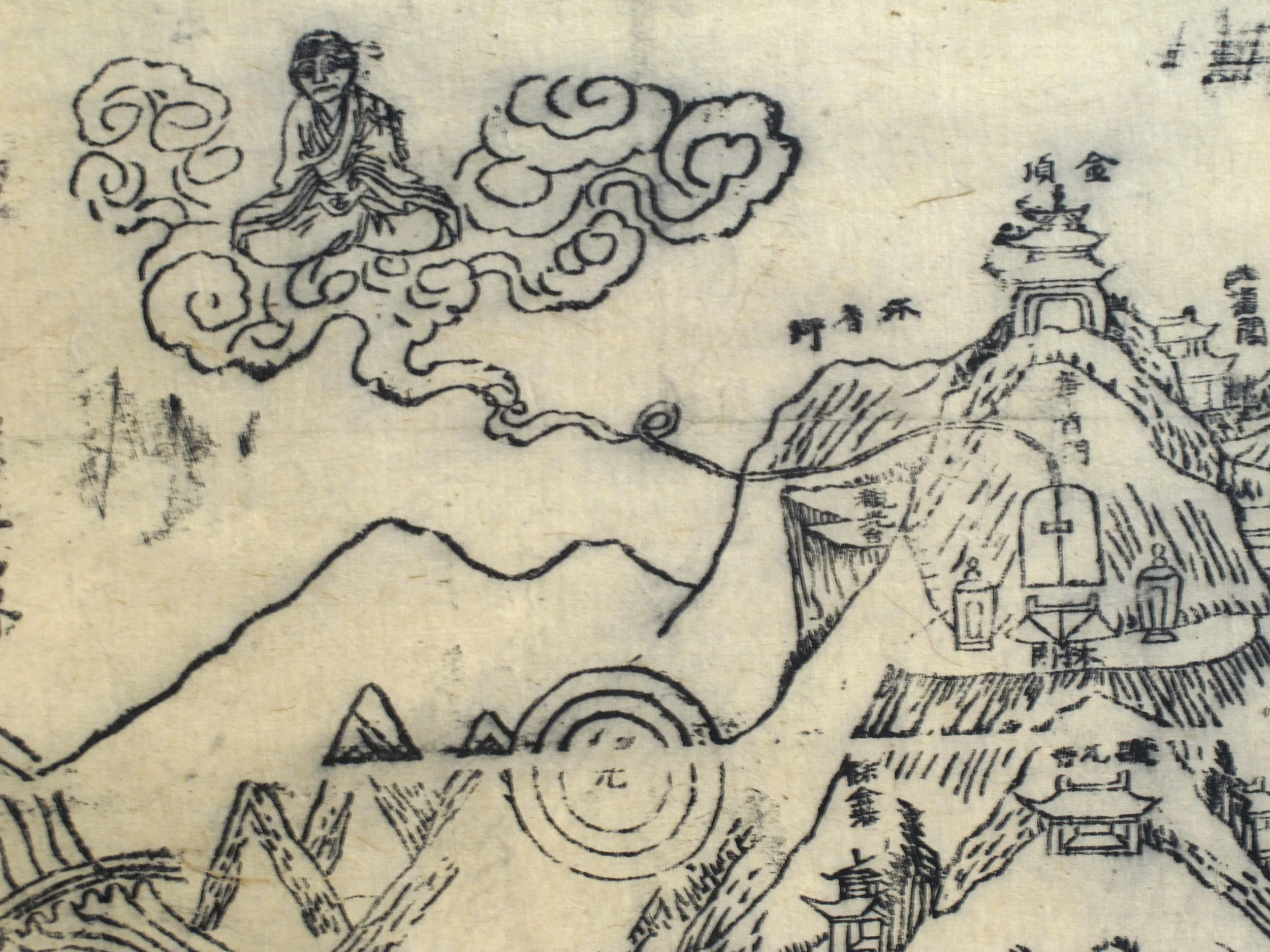

The summit: Huashou Men, Jinding, Kasyapa and Buddha’s Halo - but no pagoda

At the summit, Jinding, the golden temple – actually solid bronze with gilding – has a convoluted history. The fifteenth-century original sits atop of Wudang Shan in Hubei province, a shrine to the Daoist martial deity Zhenwu. In 1602 a shipment of bronze, intended for minting coins, was diverted by the governor of Yunnan and used to build a replica of Wudang Shan’s temple at the provincial capital, Kunming. Around fifty years later the ruler of Lijiang, north of Jizu Shan, decided that this temple would increase his family’s fortunes, and had it relocated to the mountain’s summit (a replacement was built afterwards in Kunming by the warlord Wu Sangui). Then Red Guards destroyed the one on Jizu Shan during the 1960s, so the temple there today is yet another copy.

Jizu Shan is also famous for its views, again summarised by Huang Xiangjian: “From the pagoda at the very top, as far as I could see lay the thousand peaks and myriad ravines of the Nanzhao [Kingdom]. The billowing colours of green and blue were indescribable. Then, when I gazed westward, there were mountains that looked like a [white] jade dragon stretching forward, unbroken, a thousand li.”

The three peaks at the upper right of the print are Daxue Shan, the Great Snowy Mountains of the Tibetan Plateau – in reality, they should be on the other side, where Kasyapa floats on a cloud. Below him, concentric circles are an atmospheric effect called “Buddha’s Halo”, rainbow rings surrounding your shadow on clouds below the summit.

The characters “勅建” in the map’s title translate literally as “Built by Imperial Command”. But the block of text at the top uses 勅 in a religious sense to describe Kasyapa’s decision to wait for Maitreiya, something like “holy oath”, so the sense is that Kasyapa’s entombment turned the mountain into a holy monument – that’s my interpretation at any rate (thanks to Li Maoqing for pointing this out).

Xu Xiake

Xu Xiake meeting Mu Zeng – statue outside the Mu Mansion in Lijiang, funded by Mu Zeng’s descendants

The mountain’s most famous tourist was the great traveller and diarist, Xu Xiake (徐霞客, 1587–1641). In 1636, aged 50, Xu set out on a four-year trek from his home in Jiangsu Province to southwestern China because “old age approaches and I cannot wait any longer”. With him were two servants and a Buddhist monk named Jingwen (靜聞), who wanted to visit Jizu Shan so badly that he had written out the Lotus Sutra in his own blood as a gift for the temples there.

The journey didn’t go well. One of the servants ran off in the first few weeks, and then the party was violently robbed in Hunan; Jingwen died of his injuries leaving Xu to carry his ashes and the sutra to the mountain. Xu arrived on Jizu Shan at lunar New Year 1638 to a warm reception from the monks. He donated the sutra and buried Jingwen’s ashes, and mourned that with his travelling companion dead, “I can now only admire landscapes alone.”

A month later, Xu headed north from the mountain to visit Lijiang, capital of the Naxi Kingdom. Lijiang’s hereditary ruler Mu Zeng (木增; 1587–1646) was an ardent Buddhist who had funded recent maintainance of Jizu Shan’s temples (it was his descendant, Mu Tianbo, who would have the golden temple moved from Kunming to the mountain). The Mu clan had risen to power during the thirteenth century; they governed the region in China’s name, and had conquered several neighbouring Tibetan territories.

Impressed by Xu’s literary skills, Mu Zeng asked him to return to Jizu Shan and compile a gazeteer. Xu agreed, but first spent several months exploring southwestern Yunnan, visiting Dali, Baoshan and Tengchong near the Burmese border. He returned to Jizu Shan in late August 1639 and stayed until the following April to research his guide, visiting over seventy temples, chatting to monks, and investigating the mountain’s climate, geology and religious history.

But by this time Xu was seriously ill. His skin had broken out in sores, and he’d injured his ankle somehow; he always pushed himself hard on his travels, eating poorly, hiking in all weathers and staying in cheap lodgings. Then on the Double Ninth Festival, when Chinese visit family graves, Xu’s remaining servant fled, taking all the luggage with him. Sick and dispirited, Xu had completed only the first four chapters of his gazeteer (it was finished in twelve sections after his death). Mu Zeng arranged for him to be carried in a sedan chair back east to Hunan province, where Xu caught a boat to his hometown. His diaries end on 14 September 1640, and Xu died in bed the following year.

How old is the map?

The first clue to the map’s age is at the summit – one of the most distinctive buildings there today, the square-sided Lengyan Pagoda (楞严塔), is missing. Built to a ninth-century design, the pagoda only dates to 1929, after a previous version – the one which Huang Xiangjin climbed for the views – was demolished in the late seventeenth century. So this woodblock was made somewhere between about 1700 and 1929.

Lengyan Pagoda, built in 1929… and not on the map. Golden Temple in front

OK, not a very tight date range. But the map’s text, and one of the temple’s names, narrow things down, as they identify the map with one of the most influential Buddhist monks of recent times, Xu Yun (虚云, 1840?–1959).

Already a noted Zen master, Xu first visited the mountain around 1890 and was not impressed: monks ate meat, dressed informally and treated the temples as their private property, refusing to allow clergy from elsewhere to join their ranks or even to visit. Xu was forced to sleep on a rock out in the open, and left depressed that Buddhism on Jizu Shan had become so debased.

In 1900, Xu was in Beijing during the xenophobic Boxer Uprising and its violent suppression by foreign forces. He joined the Imperial court’s flight west to Xi’an, where his learning impressed influential ministers and officials. But he soon abandoned Xi’an’s clamour, and in 1902 drifted back to Jizu Shan. Climbing to the summit, he vowed to build his own temple on the mountain in defiance of local hostility.

Amongst Xu’s disciples were two provincial bigwigs, Commander-in-Chief Zhang Songlin and General Li Fuxing. Around 1904 they invited Xu to Dali’s Chongshen Monastery, but he told them of his vow and asked permission to settle on Jizu Shan instead. With extra help from Binchuan’s sub-prefect, Xu acquired the mountain’s derelict Yingxiang temple (迎祥寺, also known as Boyu nunnery, 钵盂庵). Now that Xu had powerful backers everyone was keen to welcome him, and soon restoration of the temple had begun.

When funds ran short, Xu set off around the region to raise subscriptions. Arriving at Tengchong, down near the Burmese border, he performed a funeral service for a scholar who had died a few days earlier aged 80, having first predicted Xu’s arrival to his family. The story spread around town, and when Xu asked for contributions, the whole of Tengchong donated.

Xu returned to the mountain and “bought provisions for the community, erected buildings with extra rooms, set up monastic rules and regulations, introduced meditation and expounding of the sutras, and enforced discipline according to Buddhist Precepts. That year, the number of monks, nuns, male and female lay devotees who received the commandments was over 700 persons. Gradually, all the monasteries on the mountain followed our example and took steps to improve themselves; their monks again wore the proper monastic garments and ate vegetarian food.”

In 1907, after another fund-raising tour around Southeast Asia, Xu joined a Buddhist delegation to Beijing, to petition the court against taxing monasteries. After their mission succeeded (largely because ministers Xu had met years earlier in Xi’an supported their cause), Xu also requested a complete set of the Tripitaka – the vast Buddhist canon – for his monastery on Jizu Shan. The emperor approved:

His Imperial Majesty has been pleased to bestow upon Yingxiang Monastery of Boyu Peak of the Chickenfoot Mountain, Yunnan Province, the additional title: ‘Protecting the Nation Zhusheng Zen Monastery’, plus … the Imperial Dragon Edition of the Tripitaka … All officials and inhabitants of the locality are required to obey and execute this Imperial edict and give protection to the monastery.

After a final round of alms-collecting in neighbouring countries, Xu finally returned to Jizu Shan around 1910; it took over 300 pack animals to carry the Tripitaka up the mountain to his imperially-renamed Zhusheng Temple (祝聖寺). Xu stayed at Jizu Shan until 1928, after which he was appointed abbot to a monastery in eastern China.

Four halls and a pond at Zhusheng Temple (with barely legible label, 祝聖寺, above the rectangular pond)

So back to the map. The final vertical line of text at top left states that the map was drawn at Zusheng Temple by Xu Yun; as the temple name’s was only bestowed in 1907, and Xu didn’t return to the mountain until 1910, this would date the map to somewhere between then and 1929, when the pagoda was rebuilt on the summit.

Incidentally, I’ve searched everywhere online for another copy of this map, without success – this could be the only one.

Thanks, as always, to Li Maoqing for extra research.

Elizabeth Kindall Experiential Readings and the Grand View: Mount Jizu by Huang Xiangjian

https://www.jstor.org/stable/23268279

Xu Yun Empty Cloud, The Autobiography of Chinese Master Xu Yun, translated by Charles Luk (1980)

https://www.thezensite.com/ZenTeachings/Translations/Empty-Cloud_The_Autobiography_of_Xu_Yun.pdf