The Guan Yu Stone Rubbing Mystery

Here’s a rubbing taken from an engraved stone tablet – a stele – of Guan Yu, a third-century general later deified as the incarnation of martial righteousness. Guan is riding the legendary Red Hare, a horse which could gallop “1000 miles in a day”, and holds his trademark halberd, Green Dragon.

Dangling from rings above Guan Yu’s head is a square seal engraved with stylised characters for “Lord of Hanshou District” (漢壽亭侯), one of Guan’s titles. The text on the left says the seal was dredged from a river at Yangzhou, in eastern China, “on the eighteenth day of the tenth month of the third year of Hongzhi’s reign” (mid-November, 1490). The seal was made of jade and weighed about 750g.

The text on the right is written in classical Chinese, not my strong point, but implies that the discovery of such a great treasure must mean that the heavens are watching over the nation, and will revitalise and protect it in times of crisis. Flanked by dragons, the characters in the rectangular box at the top (御製) mean that the stele was engraved by imperial command.

Guan Yu and the Hanshou seal

Long after his death in 220 AD, Guan Yu – also known as Guan Gong (Lord Guan) or Guan Di (Emperor Guan) – was immortalised in the fourteenth-century historical epic, Romance of the Three Kingdoms. The tale, based on historical records but greatly embellishing Guan’s heroics, charts the fall of the Han dynasty and the division of China by competing warlords, each claiming to be the true inheritors of the Chinese empire. Guan Yu, along with his oath-brothers Liu Bei and Zhang Fei, represented the westerly kingdom of Shu (modern Sichuan).

In chapters 25–26 of Three Kingdoms, Guan Yu gets separated from his oath brothers during fierce fighting around the town of Xiapi, and is captured by the novel’s arch-villain Cao Cao. Guan is treated well but steadfastly refuses to serve the rival warlord: if he discovers Liu Bei is still alive he will leave Cao Cao to rejoin him; and if Liu is dead, he will commit suicide to honour his oath. But after accepting the gift of Red Hare, Guan feels obligated to perform a service for Cao; he rides boldly into a rebel camp and takes their leader’s head, after which the emperor appoints him Lord of Hanshou, “the seal of which was cut and presented to Guan Yu”.

Aside from the description on the stele, another version of the seal’s rediscovery appears in the miscelaneous writings of seventeenth-century historian Tan Qian (談遷). Tan says that, according to contemporary chronicles, the seal – beautifully decorated with archaic dragon-like creatures and marked “Lord of Hanshou District” – was found in the river near Yangzhou at the time of governor Yang Ji (楊集, c.1454). By the 1620s the seal had passed into the hands of Shen Xiangguo (沈相國) of Wucheng; made from ancient jade, it was pierced so a cord could run through it.

Three versions

Left to right: Met Museum, mine, Korean Research Institute of Ancient Asian Woodblock Prints

Searching around online, I’ve found at least three different versions of this rubbing – in New York’s Metropolitan Museum (according to a photo in Clarence Day’s “Chinese Peasant Cults”, the original stele for this was in Hangzhou), on the Korean Research Institute of Ancient Asian Woodblock Prints’ website, and mine – meaning that at one point there must have been at least three different stone carvings. Though obviously based on the same design, which one of the rubbings – if any of them – is from the “original” stele, there’s no way of knowing.

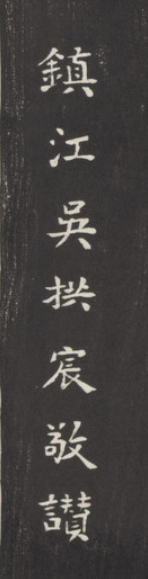

There are some important differences between the three versions. Mine is missing a vital bit of text found on the others: a line on the far left reading “Respectfully [written by] Wu Gongchen of Zhenjiang”. Wu – who was born in the last year of Wanli’s reign in the Ming dyansty (1620), and died in the early years of the Qing (after 1661) – served as a magistrate, and the text is presumably carved in his hand.

Except that it might not be. While the caligraphy on both my version and the Met’s is the same, that on the Korean copy is in a different handwriting (even though it does include Wu Gongcheng’s byline). Which version is an accurate copy of Wu’s caligraphy I’ll leave to the experts.

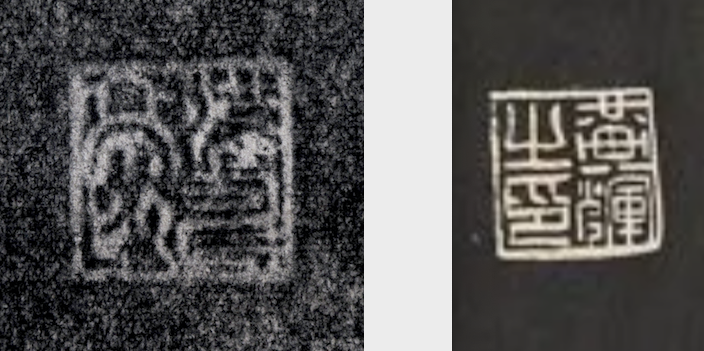

Met text on left, Korean text on right. Same text, different hands

Another major difference between the prints is the artist’s seal mark on the lower right-hand side, near Guan Yu’s elbow. It reads Huang Hui (黃輝) in the Met version, possibly Hong Shou (洪壽) on mine (but not clear enough to be sure), and is missing completely from the Korean rubbing.

Met’s artist’s seal on right, mine on left

There are plenty of other variations too – the border dragons, Guan Yu’s seal cut in reverse on the Korean version (with the characters raised instead of incised), the counterweight spike on Guan Yu’s halberd… but you get the idea.

How old is the design, and the rubbing?

Assuming that Wu Gongchen indeed wrote the text, the original version of this tablet – whichever one that is – must date to the late Ming or early Qing dynasty. Either dynasty would have appreciated the symbolism. If it was late Ming, the empire was falling to pieces through the corruption and incompetence of its court, and would have found comfort in the powerful image of Guan Yu, and the notion that the rediscovery of his seal guaranteed heavenly protection for the Ming. For their part, the Qing – who were ethnically Manchu, not Chinese at all – actively promoted the cult of Guan Yu, hoping to win widespread acceptance for their new rule by identifying with a Chinese hero.

The popularity of Guan Yu’s cult also goes some way to explaining why there were multiple versions of the stele made, each one presumably for a different Guan Yu temple. But as far as I can discover, none of the stone tablets survive today.

I have no idea how old my rubbing is, but I’d guess to pre-1950; the only even vaguely dateable ones are in the Met, which has two copies (one donated in 1949, the other in 1959), though there’s no information on when their rubbings were actually made. Anyone with more information, please get in touch!

Many thanks to CS Tang for reading the seal script.