A Warrior’s Phoenixes

Here’s a stone rubbing of a pair of phoenixes amongst peonies, overshadowed by a wutong tree. Peonies are considered the “king of flowers” in China, often paired in art with the phoenix, which usually represents female power. But here, as both male and female phoenix are shown, the peonies simply emphasise the regal nature of the birds.

A beautiful rubbing, about 90 x 180cm. It’s unmounted, so the quilted paper is still deeply embossed from being pressed into the stonework during the rubbing process

The tree links the picture to verses in the shi jing, a collection of Chinese poems dating back perhaps three thousand years. Phoenixes are described flying about, rustling their feathers, singing and perching in wutong trees, while a host of officials and common people gaze up at them in admiration – an allegory about loyal subjects working in harmony with a wise, heavenly ruler.

The original stone tablet was carved in the late nineteenth century and still survives at Baidi Cheng, an islet in the Yangzi River near Fengjie town in Sichuan, immediately west of narrow Qutang Gorge. The island houses a small complex of temple halls and a former British customs post and signal station, now given over to waxworks and artefacts relating to Baidi Cheng’s history – including over seventy old stone tablets.

The Chinese text on the right tells how Baidi Cheng, White Emperor City, was founded by the first-century general Gongsun Shu and named after the dragon-like swirls of white mist which gathered about a well there. “White Emperor” was also the title that Gongsun adopted after he rebelled against the ruling Han dynasty and established a breakaway kingdom in Sichuan. He was later defeated by the Han emperor Guangwu, who took Baidi Cheng as his own.

Baidi Cheng moulding (actually it says Baidi Miao, Baidi temple), with well and dragons, above entrance gate

Two centuries later, as the Han dynasty finally fell apart and China split into three competing kingdoms, Baidi Cheng was occupied by the forces of Liu Bei of Shu (Sichuan). Around 220 AD Liu attacked the southern kingdom of Wu, but his forces were defeated, his oath-brother Guan Yu was killed, and his army chased right back to Baidi Cheng by the Wu general Lu Xun.

According to the historical novel Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Lu arrived at Baidi Cheng to find that the strategist Kongming had built a maze of rocks in the form of an eight-side bagua symbol. Undaunted, Lu led his men into the maze, only to be overcome by dust storms and frightening visions. He eventually escaped but, unnerved at Kongming’s magic, fled back to Wu.

The text finishes with something like “I also retreated to this “place of forests and springs” and lingered here for a long time practicing calligraphy and painting. Bao Chao [跑超], named Chunting [春霆], winter, tenth year of the Guangxu emperor’s reign (1885)”.

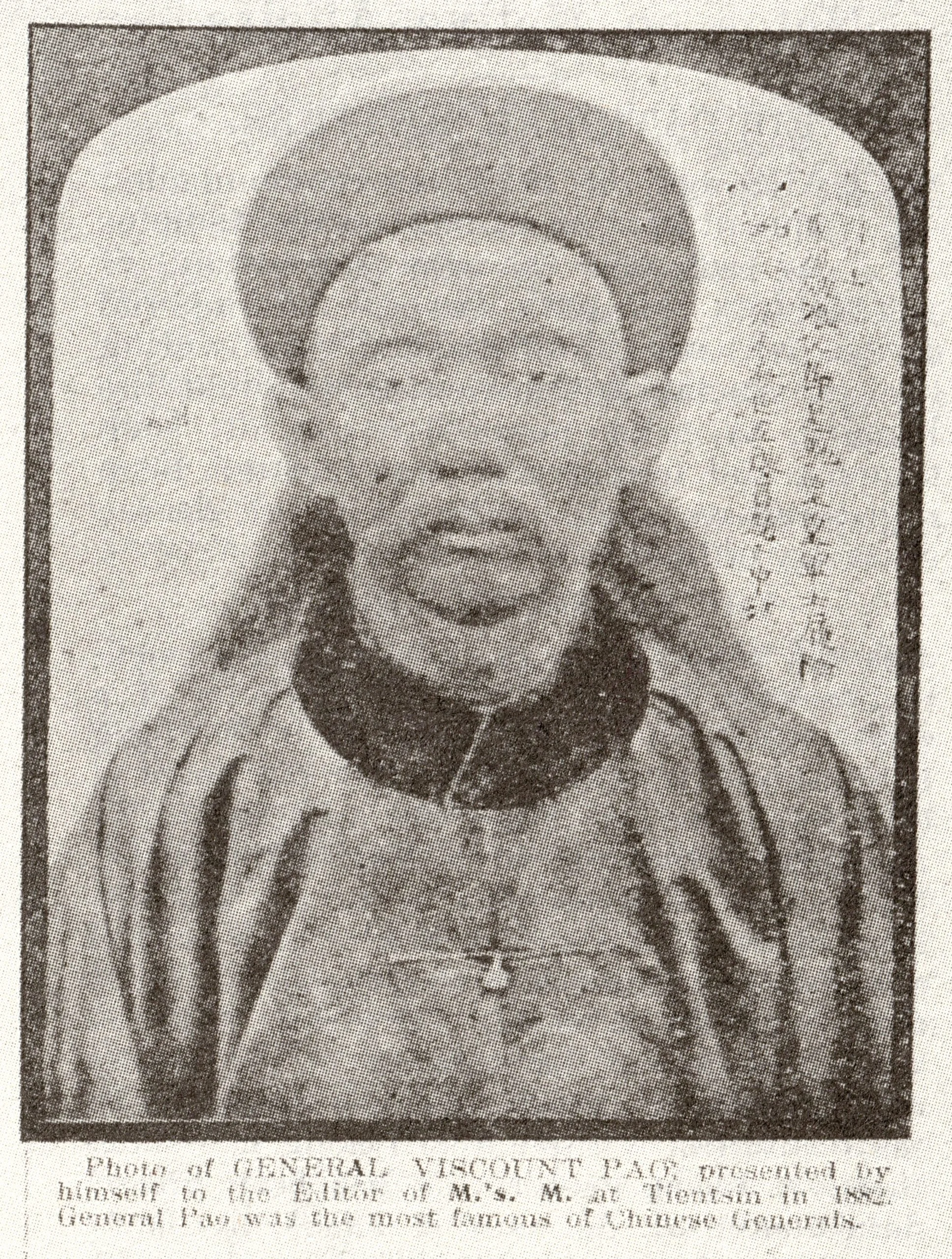

The only photo I could find anywhere of Bao Chao, from Mesny’s Chinese Miscellany, volume IV

Bao Chao seems an unlikely artist. Born in 1828 at Anping village, just upstream from Fengjie, the family moved to town after his father died, where Bao sold tofu and coal.

When the Taiping Uprising broke out in 1852 he enlisted and became an officer in Zheng Guofan’s navy, fighting the rebels along the Yangzi valley at Yuezhou, Wuchang and Hanyang. Bao’s fearlessness in battle got him noticed by the regional governor Hu Linyi, and he was promoted out of the navy as a lieutenant-colonel in the Hunan Army. His 3000-strong “Ting’s Force” (霆軍) went on to battle the Taipings across eastern China, liberating towns from rebel control and at one point even rescuing Hu Linyi.

Bao was awarded batulu status for bravery – in later life he was said to have over a hundred battle scars – and in 1861 was appointed provincial commander of Zhejiang, but was so busy actually fighting he couldn’t take the position up, or to return home to mourn after his mother died.

Qutang Gorge, the narrowest and shortest of the Three Gorges, just downstream from Baidi Cheng and Fengjie town. The sharp summit on the left is Wu Shan, Witch Mountain

After the Taipings were defeated and their capital Nanjing fell in 1864, Bao chased fugitive rebels down into Fujian province and is said to have executed 40,000 prisoners – nothing unusual for the times. He was made a viscount (子爵) and allowed brief leave to bury his mother’s ashes, but soon found himself recalled to deal with the ongoing Nian Rebellion.

During the battle of Yonglong River in February 1867, the Huai Army under Liu Mingchuan was drawn into an ambush and only saved from anihilation by Bao’s forces, who went on to rout the Nian. Liu however claimed that Bao had deliberately hung back, waiting for the Huai Army to come to grief before stepping in. The powerful military statesman Li Hongzhang supported Liu’s version of events, and Bao was censured.

Furious at this treatment after years of loyal service, Bao resigned from the military and retired to Fengjie, where he donated a million silver taels of his own money to rebuild the town after a catastophic flood in 1870. The British adventurer William Mesny – himself a decorated general in the Hunan Army – stayed at Bao’s palatial mansion here on two occasions, and was impressed by his honest generosity.

Nice solid calligraphy

Having been fined for allowing Imperial gifts to be destroyed in a house fire, in 1880 Bao was hauled out of retirement by the court, appointed commander-in-chief of the Hunan Army, and ordered to gather forces against a possible Russian invasion in China’s far northwest. He soon managed to be excused, citing ill-health.

In 1885 Bao was again recalled to counter the French invasion of northern Vietnam, then a Chinese client-state. He travelled with his troops to the border, but took no part in actual fighting. After a treaty with France was signed in June he returned to Fengjie, at which point he must have painted the original picture from which the stone tablet was carved.

Bao died the following year, as announced in the Peking Gazette on 7 October 1886. The emperor posthumously appointed him Junior Guardian to the Heir Apparent, his sons and grandsons were ennobled, and the Sichuan government was ordered to donate 3000 taels towards his funeral expenses. Bao was buried at his hometown, but his tomb was destroyed in 1966 during the Cultural Revolution.

So – is this picture simply illustrating those verses in the shi jing, with the phoenixes representing the emperor and his consort; or is it a comment on how Bao, betrayed by politics and forced to retire, wanted to remind those in power that they should live up to the ideal in the poem?