Applying Clan Law to Demons: Zhou Han and Griffith John

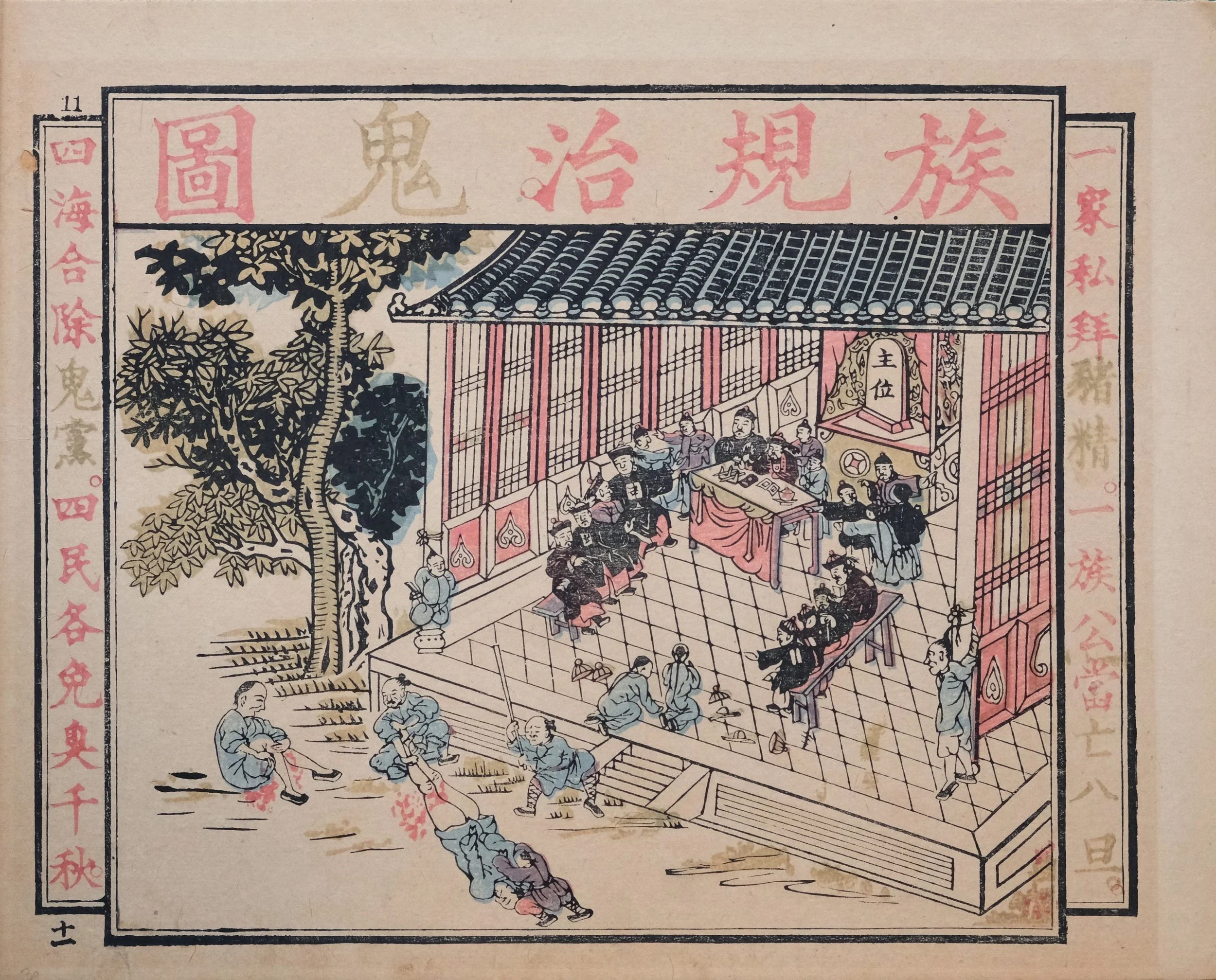

Here’s a Chinese print apparently illustrating a typical nineteenth-century court scene. Flanked by two rows of officials, a magistrate and his staff sit behind a desk judging criminal cases, while out in front the court police dole out beatings and other punishments to encourage suspects to confess. A bit savage perhaps, but part of daily life at the time.

Except that this is no ordinary court: the headstone-like board at the back of the hall marked 主位 is an ancestral tablet, the “magistrate” is the head of the clan, the officials are clan elders, and the people being punished have broken clan regulations. The title above translates as “Applying Clan Law to Demons”, and the text either side reads:

If even one family secretly worships the pig spirit [Christ],

It means their whole clan have abandoned Confucian law.

Everybody should work together to eliminate this demonic cult,

So our people can be free from its stink for all eternity.

This print is one of the least offensive illustrations from “The Complete Illustrated Manual of Obedience to the Sacred Mandates for Exorcising Evil” (謹遵聖諭辟邪全圖), a 32-page anti-Christian pamphlet published in 1891 by Zhou Han (周漢, 1842–1911). Born at Ningxiang, 40km west of Hunan’s provincial capital, Changsha, Zhou was an aspiring scholar who passed the local government exams aged just eighteen. He was appointed magistrate, joined the military and fought against a Muslim uprising in northwestern China, but became disillusioned by the throne’s conciliatory attitude towards the foreign occupation of Chinese territory. In 1884 he retired to Changsha to work in publishing but the company went bankrupt and he returned to Ningxiang.

Witnessing the growing numbers of foreign missionaries in China, Zhou felt their teachings undermined Confucian morals and he began publishing virulent anti-Christian leaflets. These proved popular and were distributed widely along the Yangzi valley. The British took exception, fearing Zhou’s xenophobic propaganda would encourage a widespread anti-foreign uprising, and complained to the Beijing government in September 1891. Bookshops selling the pamphlets were duly closed and their stock destroyed, but the regional governor Zhang Zhidong, aware that Zhou was a popular local figure amongst the influential gentry class, advised against arresting him.

What had made Zhou so doggedly anti-Christian? After all, the religion had been known in China, on and off, for over a thousand years. There were Nestorian Christians from central Asia at the Chinese capital as early as the eighth century, and the first Catholic missionary to China, John of Monte Corvino, arrived in 1294 during the Mongol Yuan dynasty and claimed to have built a church, made thousands of converts and translated the New Testament into Mongolian. During the fourteenth century there was also a Catholic bishop at great southern port of Quanzhou.

But these early efforts fizzled out, until in 1557 the Portuguese gained a toe-hold on the south China coast at Macao. Through this gateway stepped the Jesuit priest Matteo Ricci, who was invited to Beijing by the emperor Wanli and died there in 1610 having refined the Chinese calendar, translated Confucian analects into Latin and converted several Chinese officials. The Jesuit mission survived the Ming dynasty’s collapse in 1644 and found favour with the ethnically Manchu Qing dynasty which succeeded it, introducing China to Western metalurgy, art, cartography, astronomy, mathematics and architecture, and even designing a European-style palace for the emperor’s summer retreat.

By the early nineteenth century attitudes had changed however; Christianity as a teaching had been banned in 1723 (though Jesuits continued to work for the emperor) and China began a policy of isolation from the outside world. This angered British merchants, who were paying vast amounts of silver for Chinese tea, silk and porcelain and wanted the Chinese to buy some of their products in return. So the British began smuggling opium into China, whose use as a recreational drug spread through the country and proved a huge drain on the imperial treasury. In 1840 the emperor banned the opium trade, Britain sent in gunboats to enforce it, and within two years the Qing government had been beaten into signing a treaty which opened up the country open to foreign commerce – and a fresh influx of Christian missionaries.

The famously well-educated Jesuits had shown an intelligent interest in Chinese culture, and their influence had been confined to the Imperial court. This new wave of missionaries were from humbler backgrounds, sincere and dedicated but often with little learning outside of religion. They set out with evangelical fervour to convert the Chinese masses from what they considered to be the pagan idolatory of Buddhism, Confucianism and Daoism.

From a Chinese perspective these foreign missionaries were, at best, baffling. China’s folk pantheon has thousands of gods and the idea of a single deity seemed ludicrous, while the missionaries’ desire to live simply amongst ordinary Chinese implied that they lacked influence and self-respect. The Christian tenet of forgiveness was also at odds with Confucian notions of shared responsibility, which often saw not just the criminal punished, but their entire family as well.

Missionaries also divided the wider community by supporting Christian converts involved in civil disputes. Magistrates would be reluctant to hand down judgements against them, fearing that the missionaries would complain to the foreign authorities, who would in turn pressure Chinese officials to overturn their verdicts and possibly impeach the magistrates themselves for causing trouble.

Church-run orphanages caused far more sinister misunderstandings. Most Chinese could not fathom why anybody would take on the expense of adopting the children of complete strangers unless they were somehow making a profit. The number of orphans who died of natural causes in church care convinced many that the missionaries were in fact killing them and harvesting their body parts to make Western medicines.

For all these reasons then, Chinese resentment at these intrusive foreigners and their strange religion simmered away for decades – occasionally boiling over into pogroms like the Tianjin Massacre of 1870. These outbreaks of violence were often caused by seemingly trivial events blown out of all proportion by angry mobs, but Westerners believed that they were part of a wider popular conspiracy, secretly sponsored by Chinese officials, to force them out of China.

And these fears seemed justified in 1890 when a string of riots targeting missionaries broke out in cities along the Yangzi valley. Churches and foreign quarters were looted and burned down, people beaten and killed, Christian graves desecrated. Chinese proclamations accused missionaries of kidnapping and murdering children, bribing corrupt authorities and building churches everywhere; the foreign-language press blamed Chinese secret societies for co-ordinating the trouble and fanning hatred against Westerners. The British sent in gunboats to enforce peace but tensions continued to escalate over the next decade, finally erupting in the violently anti-foreign Boxer Rebellion of 1900.

Griffith John, 1880s

So this is the background against which Zhou Han began printing and distributing his propaganda, and why the British agitated for his arrest. But strangely enough it is thanks to a Christian missionary named Griffith John (aka Yang Gefei, 杨格非), that Zhou’s name is remembered today.

Born in Wales, Griffith John joined the London Missionary Society in 1855 and was sent out to China. Energetic and soon fluent in Chinese, John built a base for the LMS at Hubei’s huge provincial capital, Wuhan, where he campaigned against the opium trade, founded hospitals and schools, and helped set up missions in adjoining Hunan and Sichuan provinces. In all he spent over fifty years in China, retiring to Britain only shortly before his death in 1912.

In 1890 John came across Zhou’s “Complete Illustrated Manual of Obedience to the Sacred Mandates for Exorcising Evils” being freely distributed at Huangpi, a northern suburb of Wuhan. He complained to the authorities: the pawnshops handing them out were closed, printing blocks for a new edition siezed and the cutters making them arrested. John’s investigations led him to believe the original edition had come from upriver in Hunan province, that the text was written by a scholar, and the fact they were being distributed through pawnshops showed they had widespread, high-level approval – pawnshop guilds having power and influence throughout China.

The “Excorcising Evils” booklet was partly inspired by an informal anti-Christian manifesto which had recently appeared, translated by John as “With One Heart We Offer Up Our Lives: An Agreement Entered Into By All Hunan”. The tract urged the public to root out and expel all members of the community who had abandoned Confucian teachings in favour of this foreign faith – replacing 天主教, Christianity, for the similar-sounding 天豬叫, “squeal of the heavenly hog”. Should converts betray China and join with foreigners in oppressing the country (using 羊人, “goat men” instead of 洋人, foreigner), the community should appeal to provincial officials for troops to be sent in to fight them.

Striking a chord with the public, Zhou Han’s works were produced in vast numbers – Griffith John estimated that 800,000 copies were printed – and the regional governor Zhang Zhidong wrote that nine out of ten people who read their anti-Christian message believed it to be true. Multi-coloured illustrations were also rare for woodblock-printed books of the time, which might have increased their popular appeal.

In 1891 Griffith John had his own edition printed at Wuhan, adding an introduction denouncing Zhou Han and a commentary on each print in English (these tend to be the examples which have survived in collections today). He sent samples off to the British authorities, which is what led to Zhou’s work being suppressed and his distributors arrested.

One of those imprisoned was a distant cousin of Zhou’s named Tang Menglian, who had been caught carrying “a hamperfull of these publications for general distribution”. Zhou wrote a letter to the Hubei governor, Tan Jixun (譚繼洵), begging him to have his relative released; if anyone should be considered guilty for defending Confucian laws and attacking the “depraved heresy” of Christianity it was Zhou himself, and he asked to be arrested in his cousin’s place and come to the provincial capital for punishment. Failing that, he was prepared to travel to Beijing and seek justice from the emperor himself.

Griffith John claimed that after reading Zhou’s letter governor Tan immediately released Tang, along with the others suspects. John later blamed the Yangzi riots on Zhou’s publications, claiming that in every case he could trace their arrival to shortly before trouble broke out at each city. This alarmed Zhou’s family, who – fearing they would be accused for not keeping their relative under control – did their best to ensure that all his pamphlets were gathered up and destroyed. Zhou himself was left at large for the next few years.

In the late 1890s, foreign powers began carving China up into “Spheres of Influence”. Zhou wrote a new tract denouncing this fresh meddling in China’s affairs, and this time the British authorities managed to have him arrested. Zhou was put on trial as a deranged agitator and, despite public appeals to have the case dismissed, was imprisoned in 1898.

And in jail Zhou stayed – despite being pardoned in 1907 – until his family forcibly carried him home. Although by now elderly and in poor health, he immediately began roaming the streets with a walking stick, handing out his leaflets once again. He died in 1911.

Further reading

The Anti-Foreign Riots in China in 1891 (North China Herald, Shanghai 1892)

John, Griffith

– A Voice From China (James Clark & Co 1907)

– The Cause of the Riots in the Yangtse Valley (annotated reprint of Zhou Han’s 謹遵聖諭辟邪全圖, https://visualizingcultures.mit.edu/cause_of_the_riots/cr_book_01.html)