An elephant at the Yichengyong Print Workshop 一頭大象在義成永畫店

新春大喜: “Great New Year Celebrations”

Here’s an unusual new year woodblock print featuring an elephant. It’s signed bottom left by the Yichengyong Print Workshop of Tianjin, founded in the late nineteenth century by three brothers working in partnership: Yang Yongyi (楊永義), Yang Yongcheng (楊永成) and Yang Yongxing (楊永興). In 1921 Yang Yongxing alone took over the business, inheriting over a thousand printing blocks.

Yichengyong was based in Nanzhao, one of the thirty-six villages of Tianjin’s Nanxiang district (天津南鄉南趙莊) – roughly where the south train station is today. It was said of Nanxiang that "every household was skilled in printing and every household was skilled in colouring”; often only a design’s outline was printed, with colours overpainted by hand. Yichengyong was famous for producing enormous door god prints and also specialised in New Year pictures, in demand for decorating the home every Spring Festival.

Photo from National Geographic Magazine, November 1934, showing a pair of large Tianjin-style door god prints, possibly by the Yichengyong workshop

According to Yang Peng (楊鹏), an eighth-generation Yichengyong inheritor:

“As soon as the 15th day of the eighth lunar month passed, the whole family would start working on New Year pictures. Grandma, mom and aunt would make prints of the Kitchen God and the God of Wealth, while grandpa and dad would be in charge of applying the colours. The Kitchen God ... had its own particular way of being displayed. For example, there was a saying that "the rooster goes up on the kang [heated brick platform], the dog barks at the door"; this meant that, with the rooster and dog which feature at the bottom of Kitchen God prints, the print should be hung up so that the rooster faces towards the interior of the house, while the dog faces towards the outside.”

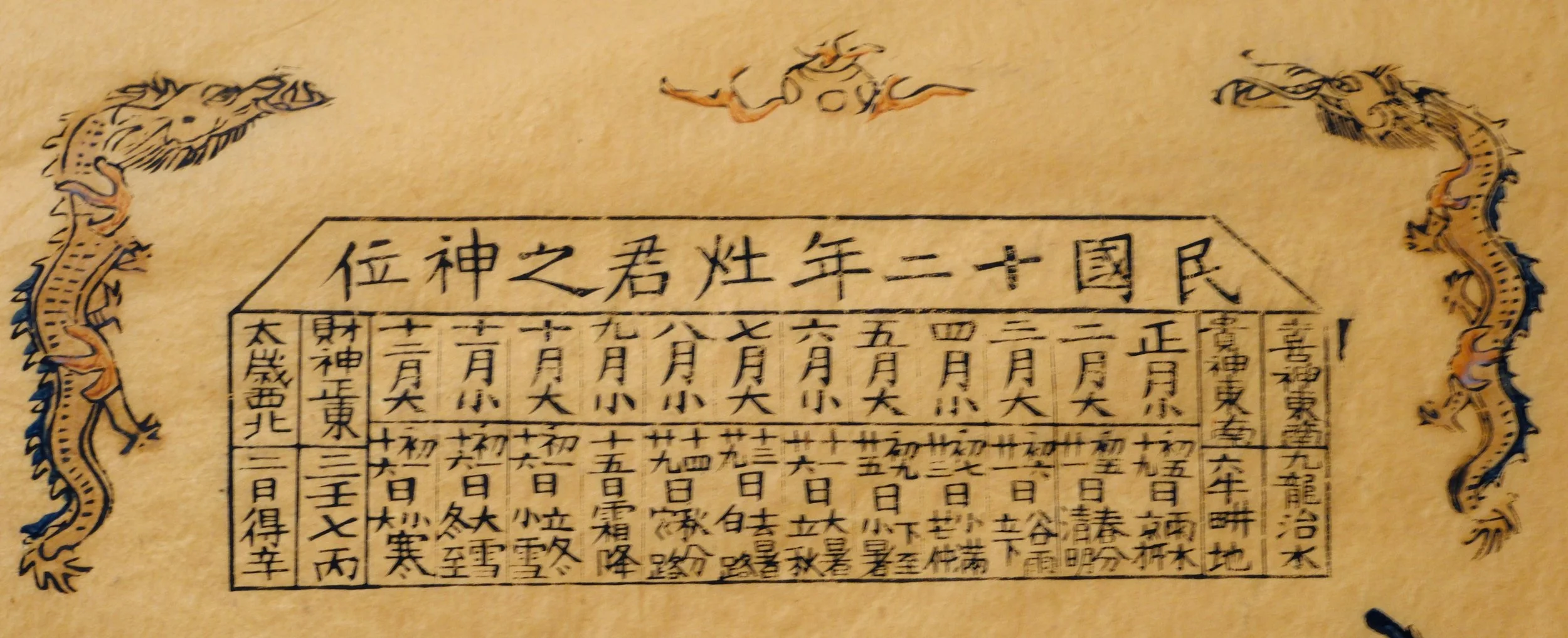

Calendar and pearl-chasing dragons

Back to this print. Up top a pair of flying dragons flank a calendar reading 民國十二年灶君之神位 or “Shrine of the Kitchen God, Twelfth Year of the Chinese Republic” (1923) – just a few years after Yang Yongxing took over Yichengyong. But the design itself is a bit older: calendars were cut for the current year on a separate piece of wood, which was then morticed into the print’s main block – otherwise studios would have needed to recut the entire design each year.

The first sign of the main block’s actual age is the figure seated left underneath the festive canopy. He’s wearing the formal robes, hat and bead necklace of a top-ranking Qing dynasty civil official, dating the design to before 1912. The staff presenting him with a round tablet reading “Spring” (春) and scroll announcing “Joyful News” (喜報) are dressed in similar costumes, one wearing a peacock feather – a badge of honour – on his black felt winter hat.

Herdboy and Spring Ox

At right are the herdboy and spring ox who appear in Chinese lunar almanacs. Almanacs include farming tips for the coming year, and the herdboy wears only one shoe (the other is slung on his pole), predicting balanced weather conditions. He holds either a food hamper or possibly a bridal box; almanacs were also used to calaculate favourable days for weddings. Along with the seated official – an Imperial representative – the ox echoes the springtime ceremony at Beijing’s Xiannong Si (先農寺; Temple to the Original Agriculturalist), where the emperor opened the farming season by ritually ploughing a furrow in a specially-prepared “field”.

On the ox’s back, two young boys support a gigantic lucky coin engraved with the characters for Xuantong (宣統). This is the reign name of Puyi, China’s last emperor, in power 1908–1911 – a final date range for the original design. The peach on top of the coin symbolises longevity, as does the crane flying above. The crane carries a scroll, a certificate of passing the Imperial exams; a crane badge was also worn by top-ranking civil officials. So the boys, peach, coin and crane are wishes for children, long life, wealth and outstanding scholarly achievement.

Mahout with goad astride the elephant’s back. Yichengyong signature lower left

And finally to the elephant. In Buddhism elephants are a symbol of wisdom, but as the design serves no religious purpose it most likely depicts one of the Burmese tribute elephants driven overland to the Chinese court at Beijing, escorting gifts of ivory, gold and gemstones. The elephants were housed in special stables and used in Imperial ceremonies, and so came to symbolise the emperor himself. As the last such tribute mission was in 1875 – accompanied as here by mahouts wielding spiked elephant goads – it’s possible that this print is an updated version of an even earlier block recording the event. At any rate, this elephant represents wishes for an auspicious New Year, with vast riches rolling in from afar. (For the whole history of elephants at the Qing court, see my blog post here.)

I’ve only seen elephants in two other Chinese prints, and both follow the same New Year theme by pairing the elephant and spring ox. So a broader meaning of the entire picture might be balancing hoped-for material wealth (the elephant) with the blessings of a rich agricultural season (the ox).

Other elephant prints. The more complex version of mine, also from Tianjin, includes a banner with the idiom 萬象更新, “Countless Natural Phenomena Renewed” (a pun on 象, which can mean both “phenomena” or “elephant”), implying a fresh start for the new year. The other is from Fengxiang in Shaanxi, another noted woodblock printing centre

Sadly, it doesn’t seem that any of Yichengyong’s thousand or more original wooden blocks survived the twentieth century, though Yang Peng and his father Yang Zhongmin (楊仲民) continue to cut, print and paint classic designs. In recent years a good number of antique Yichengyong prints have also surfaced in museums and private archives in Japan, Europe, the US and Canada.

References

Lan Xianlin Folk New Year Pictures (Foreign Languages Press 2008)

National Geographic Magazine Coastal Cities of China (November 1934; p.614)

Rudova, Maria Chinese Popular Prints (Aurora Art Publishers 1988)

Tianjin Government Cultural Tourist Information https://whly.tj.gov.cn/tjswlzxw/jgbn/whtj/whfy/202505/t20250530_6943678.html

Yichengyong Workshop www.yichengyong.com