Tribute Elephants at the Qing Court

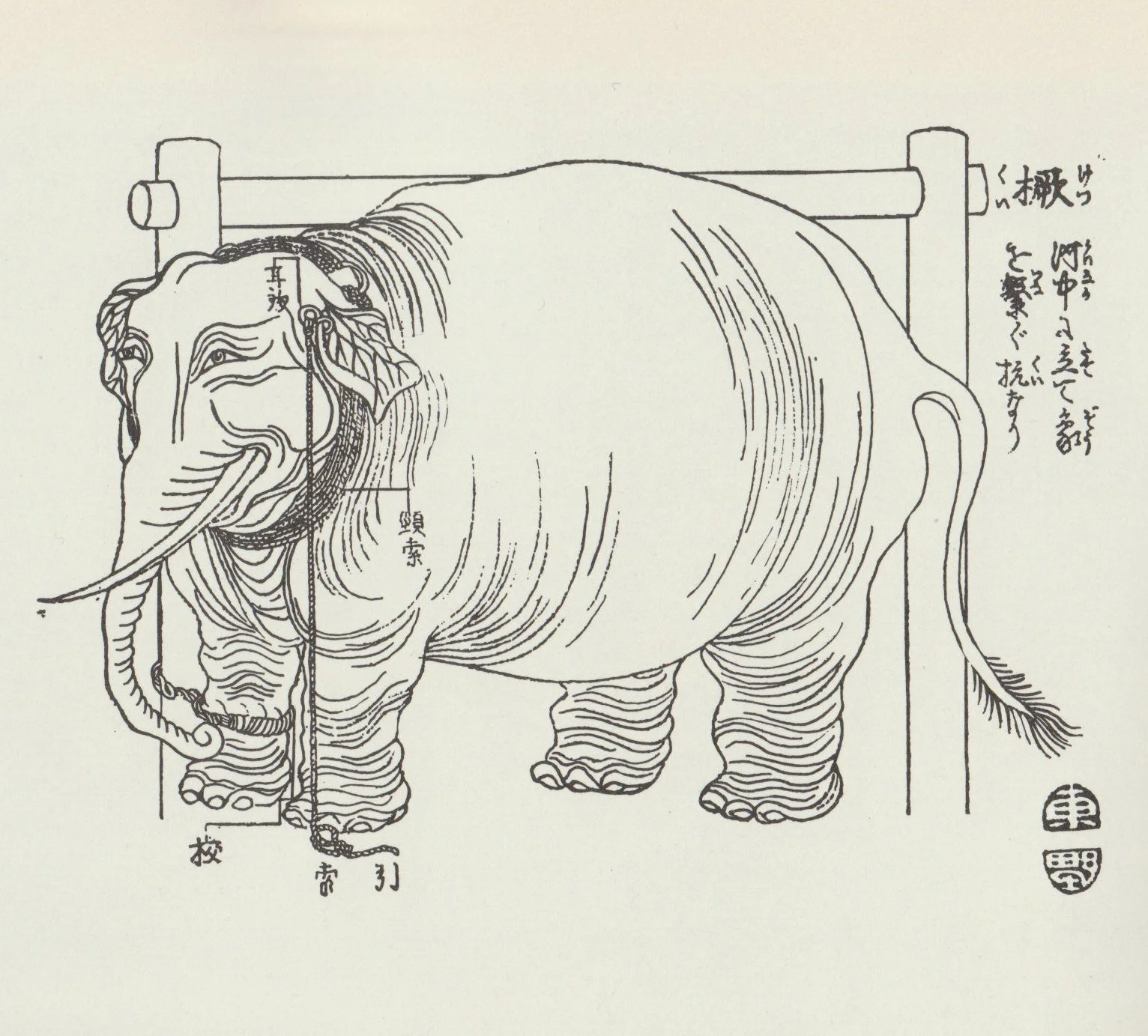

Captive elephant at the Qing court, from an encyclopedic Japanese work about the history of Beijing, 唐土名胜图会 (1805)

Elephants are associated with wisdom in Chinese lore – the bodhisattva Puxian, the very embodiment of wisdom, is depicted riding one – and the emperors themselves used them as a symbol of their own sagacity and authority. Life-sized carvings of elephants guarded the Imperial tombs, and the palace kept live ones too, in stables known as the “Tame Elephant Facility” ([馴象所), just inside Beijing’s city wall at Xuanwumen. The facility had room for forty-eight elephants (though the most they ever had was thirty-nine), each housed in a solid brick stable 36 feet by 18 feet; they were trained on the archery grounds to draw chariots and carts of precious objects for Imperial processions; to salute the emperor by kneeling down; and during court a pair also guarded the palace gates, locking trunks to bar the entrance once participating officials had entered. According to Journeys in North China by Alexander Williamson, published in 1870:

“On December 21 [of the lunar calendar] the Emperor goes in a sedan-chair to the gate called Tai-ho-men in the palace: here he mounts the elephant carriage, and proceeds to the Temple of Heaven. There be goes first to the Tablet Chapel, where he offers incense to Shang-ti and to his ancestors, with three kneelings and nine prostrations. Then, going to the great altar, he inspects the offerings, proceeds to the south gate, and taking his seat in the elephant carriage is conveyed to the Hall of Penitential Fasting.”

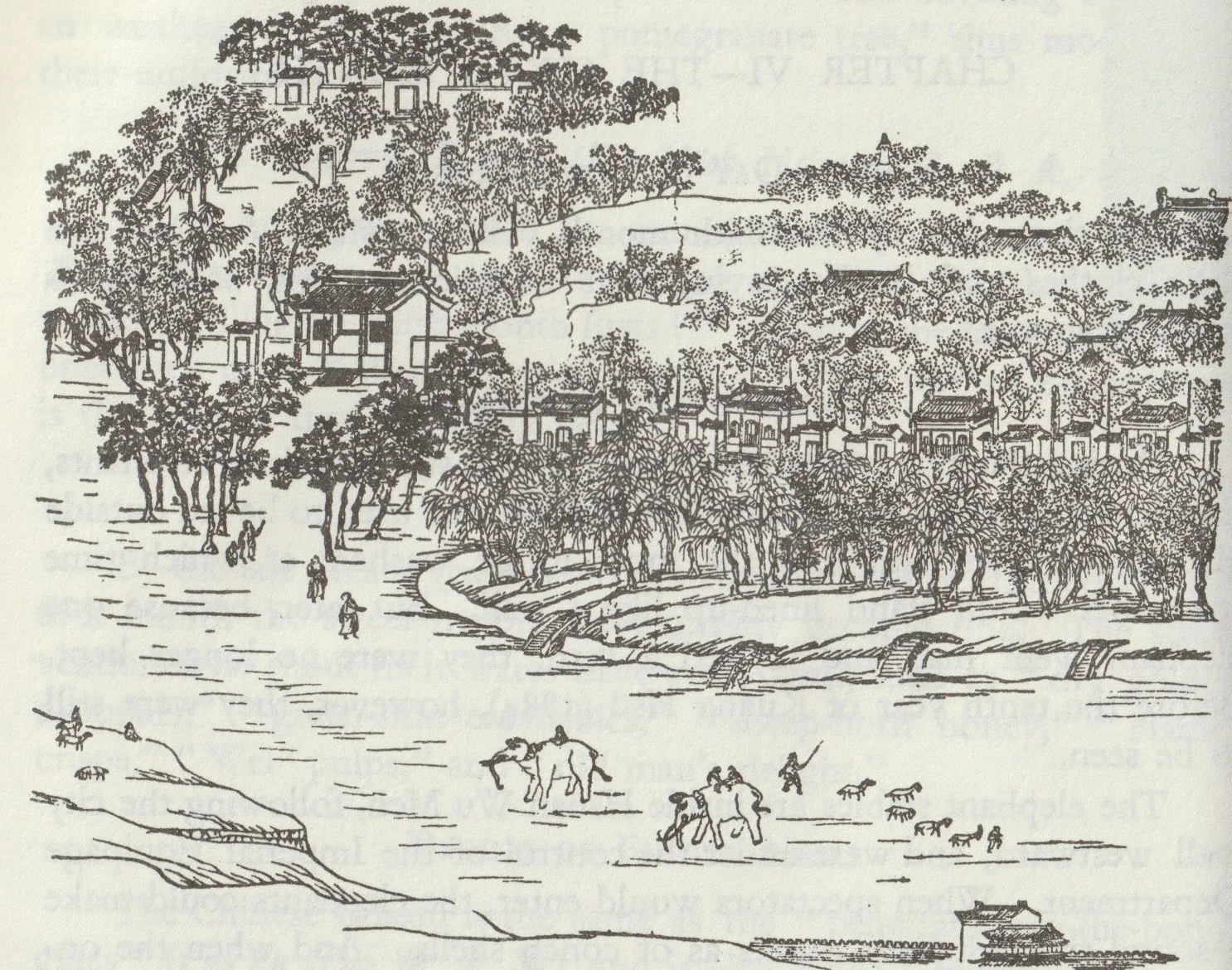

Washing elephants in the moat just south of the Beijing city walls, from a nineteenth-century painting

The public got a view of the beasts on Elephant Washing Day, the sixth of the sixth month, traditionally the hottest time of the year when scrolls, books and textiles were also aired to kill insect pests. The elephants paraded through Beijing to the washing place in the moat outside Xuanwumen, where they were scrubbed down while huge crowds of spectators paid to hear them trumpet; only when enough coins had been laid out in view would the animals perform.

Two thousand years ago elephants were widespread across southern China. But by the eighteenth century they were only found along the southwestern borderlands, and they were supplied to the Beijing court as tribute from neighbouring client states such as Vietnam, Siam and Burma. These tribute elephants had to travel around 2000 kilometres from China’s southwestern borders to the capital, crossing mountain ranges and fording deep rivers along the way, and local authorities could be fined and even demoted if the journey took too long. So grooms often deliberately ordered their elephants to go slow unless they were paid hefty bribes, until the Qing court began sending their own officers as escorts to keep an eye on things. Officials along the way were expected to provide personnel, fodder and stables, or even to build new roads or strengthen bridges. If an elephant died in transit, its ivory was sent to the emperor and the escort team was fined.

Elephants were an expensive investment: each one needed three buckets of rice and 160 pounds of straw every day, with more than a hundred grooms and trainers employed at the stables. Following Qianlong’s aggressive southwestern campaigns against neighbouring nations during the eighteenth century, so many elephants were sent in tribute that the emperor ordered that no more be delivered.

Although a few more trickled through over the next twenty years, by 1870 Beijing’s elephants had all died – probably of old age, though some say they starved to death after greedy officials pocketed their fodder money – and civil wars across China’s southwestern provinces were preventing any replacements from being sent. This was embarrassing; during processions, the emperor now had to be carried in a far less impressive sedan chair, instead of his elephant-drawn carriage.

In December 1874 the Peking Gazette – mouthpiece of the Imperial court – published an account by Cen Yuying, governor of Yunnan province, outlining the situation. Burma had presented tribute every ten years until the outbreak of the Muslim Uprising in 1856, which had plunged all of Yunnan into chaos. But now the rebellion was quashed, Burma had asked permission to resume sending tribute, and the Imperial Guard Office had ordered Cen to buy fresh elephants for the emperor. Cen instructed Zhu Baimei (朱百梅) and Wu Qiliang (吳啟亮), officials along the Burmese border, to organise it.

Elephants on the move across China

The King of Burma, Mindon Min, immediately dispatched two elephants, which arrived at the capital of Yunnan in early January, 1875. A month later, Wu Qiliang announced that the main Burmese tribute mission had crossed over the border into China and arrived at the walled city of Tengyue (today’s Tengchong). The mission comprised the envoy and his two assistants, interpreters, servants and elephant handlers – over fifty people – along with five more elephants and the tribute gifts: a letter written in gold to the Chinese emperor, a stone statue of the god of longevity, tusks, jade, gold rings, gemstones, textiles, 10,000 sheets of gold and silver leaf, sandalwood, and peacock feathers.

The embassy’s progress across China was tracked by the Peking Gazette. It caught up with the other two elephants at Kunming on 1 April 1875, and a month later crossed into Guizhou province, arriving at the provincial capital, Guiyang, on 17th May, where the elephants were quartered outside the east gate in the grounds of Junzi Ting (君子亭), the Gentleman’s Pavilion, drawing large crowds. Later that month they reached Zhenyuan, a river town on the Guizhou-Hunan border, whose scholarly prefect Wang Bing’ao (汪炳璈) wrote couplets commemorating the event:

扫尽五溪烟,汉使浮槎撑斗出; 劈开重驿路,缅人骑象过桥来

“Sweeping away the mist on Wuxi River, the Han envoy floated off by boat; Ploughing up the main post road, the Burmese rode across the bridge on an elephant”.

Ming-dynasty Zhusheng Bridge at Zhenyuan, which the elephants might have crossed in 1875. Wang Bing’ao inscribed his couplets on a pillar inside the Kuixing Pavilion on top, which he had built by to inspire students (Kuixing is the patron deity of scholarship; elephants are also associated with wisdom in Buddhism)

And so they continued northeast, crossing Hunan, Hubei and Henan provinces to reach Zhili, the area surrounding Beijing, in mid-August. Accompanied by an escort provided by Li Hongzhang (China’s foremost statesman and governor of Zhili) the embassy entered Beijing on September 10, where the North China Herald reported that they “have excited some contemptuous attention amongst the native population, who have never seen (in the present generation) anything more “outlandish” than these half-naked, turbanned and tattooed Southerners.” The elephants themselves, going at their own slower pace, rolled into Beijing at the end of September after a seven month journey from the Burmese border.

Xuanwumen was a gate in southwestern Beijing. Flanking the gate tower are “Ivory Alley” on the right, and “Elephant Stables” on the left

In the spring of 1884 one of the elephants went berserk during a ceremonial rehearsal, smashing a carriage and hurling a eunuch into the walls of the Forbidden City before stampeding west down Chang’an Avenue; Beijing’s citizens had to hide indoors for the rest of the day until it was recaptured. The elephants were never taken out in public again. Some say they died of neglect, others that in the early twentieth century the final few were moved to the new Experimental Agricultural Station, now Beijing Zoo. The site of the elephant stables was later taken over as the British Legation’s students’ quarters, and today is occupied by the Xinhua News Agency headquarters.

Many thanks to Li Maoqing for additional background information, especially on tablets commemorating the elephant envoys.

Sources

Aldrich The Search for a Vanishing Beijing

Anon Tourist Guide to Peking and Its Environs (Tientsin Press 1897)

Bodde and Bogan Annual Customs and Festivals in Peking (Taipei 1977)

Burkhardt, V. Chinese Creeds and Customs (three volumes combined, Taipei c1970)

Edkins, J. Description of Peking (Shanghai 1898)

Institute of Qing History: http://www.iqh.net.cn/info.asp?column_id=6796

Komatsubara, Yuri The Gurkha’s Offering of Elephants and the Qing Court’s Responses in 1792 and 1795 (Meiji Asian Studies, http://www.isc.meiji.ac.jp/~asian_studies/vol1/pdf/no5-komatsubara.pdf)

Lin Yutang Imperial Peking (Elek 1974)

Peking Gazette 1874–75

Rennie, David Peking and the Pekingese During the First Year of the British Embassy at Peking (John Murray 1865)

Williamson, Alexander Journeys in North China (Smith, Elder and Co. 1870)