Daoists and Tigers: Zhang Daoling at Shangqing Palace

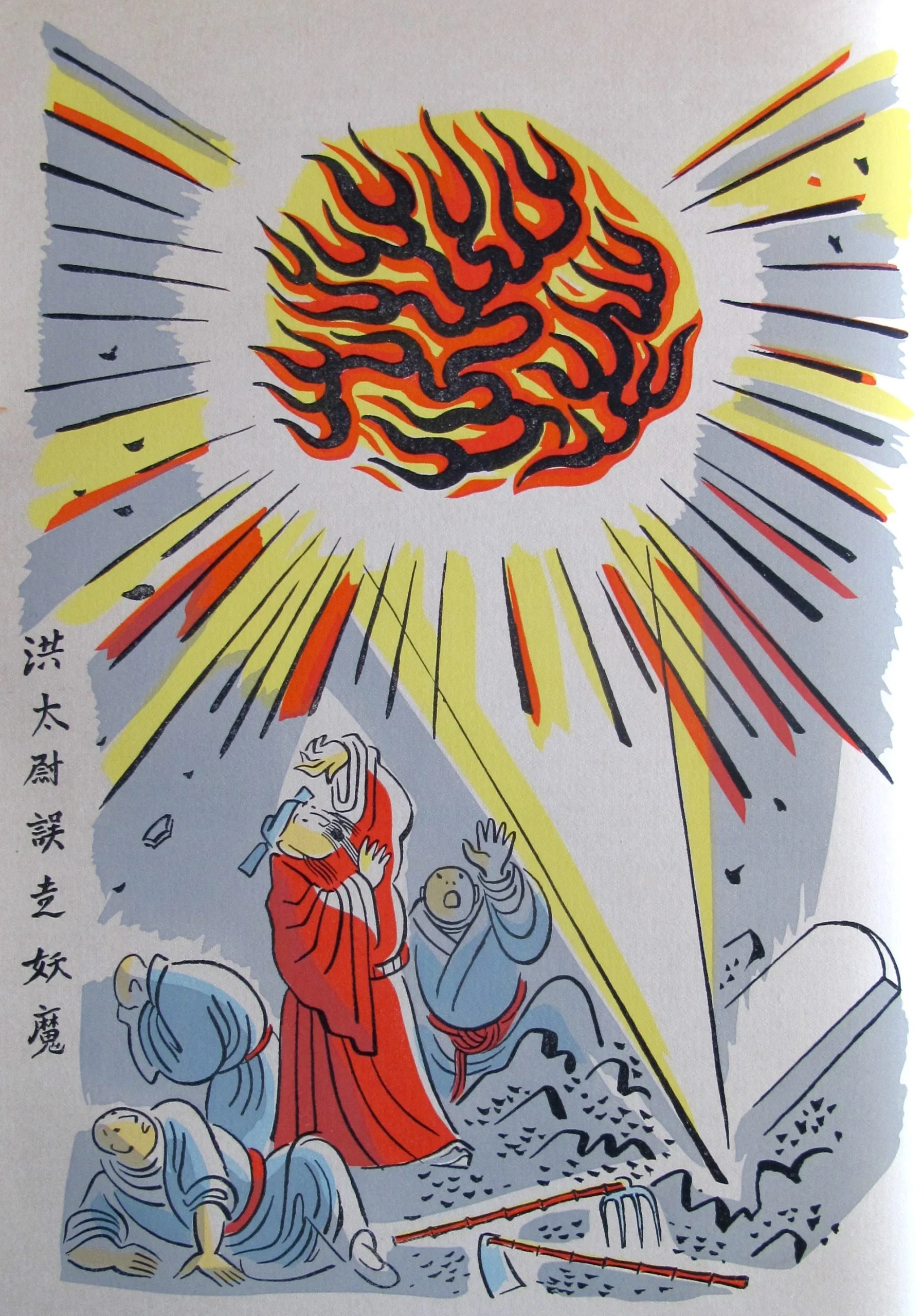

In popular lore Shangqing Palace (上清宫), a formerly important Daoist temple at Longhu Shan (Dragon-Tiger Mountain) in Jiangxi province, is probably best-known for the opening chapters of Shi Nai’an’s fourteenth-century novel Outlaws of the Marsh – aka The Water Margin – a heroic account of renegades defying the corrupt Song court. According to the novel, 108 malignant spirits are imprisoned underneath the temple for centuries until an arrogant magistrate tears off the protective seal, realeasing the spirits to be reborn as the Outlaws.

“Commander Hong Recklessly Releases the Spirits” by Miguel Covarrubias, from the illustrated All Men Are Brothers, Pearl Buck’s translation of The Water Margin

But in fact the real history of this temple goes back a long way, intricately bound up with the story of the tiger-riding Daoist patriarch Zhang Daoling (张道陵). Tradition says that Zhang was born around AD34, and served as a magistrate at Chongqing in Sichuan before tiring of court politics and retiring as a hermit, refusing appeals to return to the capital as Imperial Tutor.

Zhang eventually wandered up into the mountains of Sichuan where in 142 AD, at the age of 108 – an auspicious number in Chinese religion – he attained enlightenment. An incarnation of Daoism’s semi-mythical founder, Laozi, appointed Zhang as Chief of All Spirits (hence his outstanding ability to suppress troublesome demons), told him to prepare for a forthcoming day of judgement, and ordered him to unite the various Daoist cults under one order.

Based around the teachings of Laozi, Daoism believes that its adherents should follow “The Way”, becoming one with the natural order and thereby achieving longevity or even immortality. Originally a collection of folk philosophies, during Zhang Daoling’s lifetime Daoism was beginning to organise itself as a religion in the face of growing competition from the newly-imported faith of Buddhism, which had arrived from India during the first century AD.

So Zhang founded the Tianshi (“Heavenly Master”) Sect of Daoism at Qingcheng Shan, a mountain range cloaked in broadleafed cloud forests some 90km northwest of the Sichuanese provincial capital, Chengdu. Zhang imposed a theocracy over the surrounding district, collecting a tithe from his followers which earned the sect the name “The Five Pecks of Rice School”. He spent his later years in a cave, meditating, curing the sick and possibly authoring Reflections, a commentary on the Dao De Jing, Daoism’s core text.

By the time of Zhang’s death in 157AD, reputedly at the age of 122, the Tianshi sect had begun to expand its influence right across northern Sichuan. Unfortunately, this was a time of great political turmoil: the Han dynasty was collapsing and competing warlords saw the sect’s wealthy territory as a worthwhile prize. In 215AD, the powerful Kingdom of Wei invaded Sichuan, expelled the Tianshi sect from Qingcheng Shan and scattered its followers all over China.

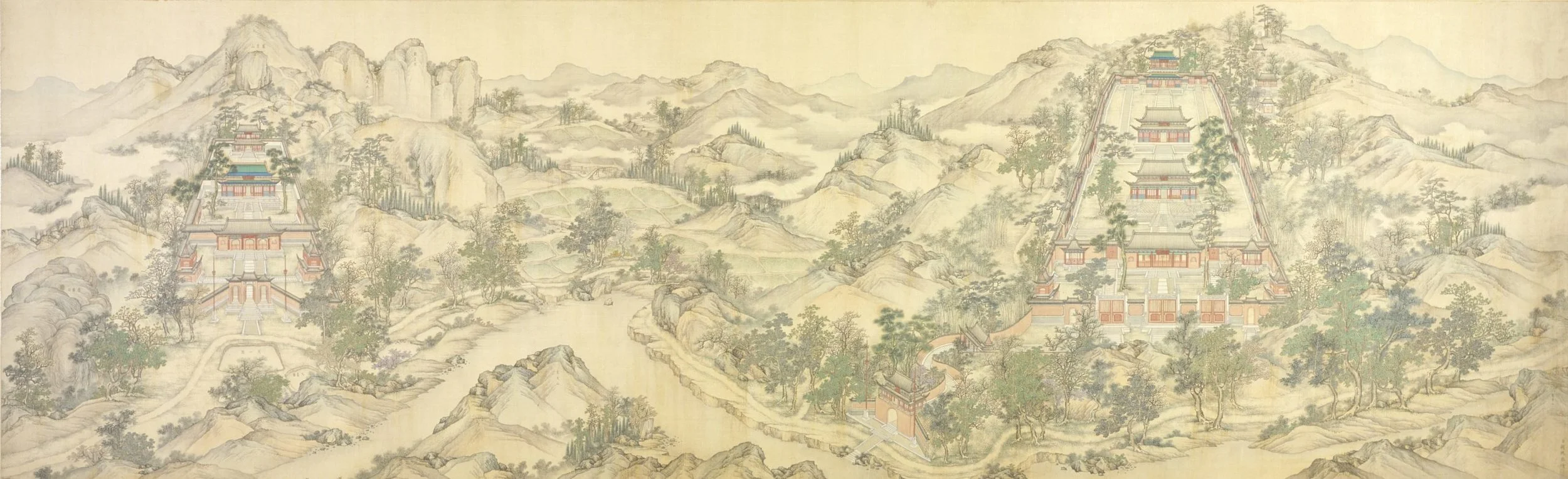

Longhu Shan Gazetteer

Legend has it that one of Zhang’s direct descendants named Zhang Sheng ended up in eastern China’s Jiangxi province at Longhu Shan, where a flurry of sheer-sided red sandstone peaks juts out of the Luxi river’s floodplains. Seeking credibility, he perhaps engineered the origin story that Zhang Daoling himself had become enlightened here: as recorded in the eighteenth-century Longhu Shan Gazetteer (龙虎山志), Zhang apparently received the “Method of the Tiger Spirit” (神虎之法) from a long-haired immortal named Liu Gen (刘根) who lived in a cave on the mountain, and learned to refine pills of immortality – the prize for any Daoist alchemist.

At any rate, Zhang Sheng re-established the Tianshi sect at Longhu Shan, and after they were granted an estate here by Imperial decree during the Song dynasty (960–1279), temples sprung up and the mountain became a hub of Taoist culture for the next thousand years. The main monastery, Shangqing Palace, was a focus for the ordination and further training of Taoist priests, and contained a magnificent library of religious texts, built in 1299.

Daoist temples at Longhu Shan

Zhang Daoling’s medical skills and control of demons made him a patron of the sick, and Shangqing Gong made considerable income not just from their substantial estates, but also by mass-producing woodblock-printed talismans of Zhang to ward off evil influences and illness. As the great collector of woodblock prints Reverend Hallock put it, Zhang’s reputation “has enabled the Taoist priests to gain great wealth by the sale of such things to the people and they themselves to be sought out as great healers … Charms with Zhang Daoling’s seal are purchased by rich and poor for goodly sums and are pasted up in the homes or are carried about on their persons.”

Which brings us to a talisman print of Zhang Daoling, bought at Shanghai by Hallock in 1927. Wielding his sword Zhang rides a tiger, which is crushing the “Five Poisons” represented by a toad, snake, centipede, lizard and spider. At the top in red are square seal stamps, a demon-repelling bagua symbol and protective talismanic script; the text below reads “Seal of the Great Shangqing Palace, Longhu Shan, Jiangxi Province”. These prints were in greatest demand for duanwu, the fifth of the fifth month, known today for its dragon-boat races but also considered the most unhealthy time of the year – stinking hot and humid across much of China – when the disease-causing five poisons are at their most noxious.

1927 print of Zhang Daoling and tiger suppressing the Five Poisons, issued in the name of Shangqing Palace. The design might reflect the story of his being enlightened by the long-haried mystic Liu Gen, who revealed the “Method of the Tiger Spirit” to Zhang

But even as Hallock bought this print in 1927, Longhu Shan’s glory days were over. The social upheaval following the abdication of China’s last emperor in 1912 saw a wave of iconoclasm sweeping China, endorsed by the Nationalist Government. In 1928 they decreed in no uncertain terms the abolition of any “useless gods” in the Chinese pantheon, including those deemed to be “quasi-religious, commercial or money-making, animistic or legendary… Temples and idols should be razed to the ground so that nothing remains.”

Although Zhang Daoling and the Tianshi sect were specifically excluded from the Nationalist’s religious blacklist, remote temples like those at Longhu Shan – loaded with valuable religious paraphernalia – became fair game for bandits and roving militias. The abbot of Shangqing Palace was chased out and in 1930 the temple burned down to its foundations, which means that the above print was one of the last issued in the temple’s name.

Indeed, this second version of the print from 1930 – also bought by Hallock – doesn’t mention Shangqing Palace at all: the text now simply reads “The Daoist Patriarch of Longhu Shan”.

1930 version of the print: no mention of Shangqing Palace

Today, Longhu Shan is flourishing once again, but more as a tourist destination than a serious Daoist site. There are rafting trips on the river, peaks and rock formations have been given fanciful names, and the region assigned a dubious history reinforcing the legend that Zhang Daoling founded his sect here, rather than in distant Sichuan. Minor temples have been renovated and, in 2014, work began excavating and reconstructing Shangqing Palace over the surviving original foundations; the project is ongoing but the gateway and several halls have been rebuilt.

Many thanks to Jarek Szymanski and Ronni Pinsler