Dryden Phelps and the Omei Illustrated Guide Book 峨山圖志

Mount Emei – or “Omei” as the locals say it – rises three thousand metres above the edge of the Chengdu plain in China’s Sichuan province, its southern face a dramatic, sheer cliff. Covered from its subtropical foothills to chilly summit in dense green forest and tangled undergrowth, full of rare plants and dripping with moisture, it’s also a holy mountain, sacred to the Buddhist incarnation of acquired wisdom, Puxian. Emei is one of the last places in China you can step back a century or more, joining a few genuine pilgrims (and plenty of tourists) seeking to gain merit by hiking to the summit; red-walled temple complexes along the way, many of whose smoky halls were founded centuries ago, provide refreshments and beds for anyone making the ascent.

Entrance to Fuhu Si, “Crouching Tiger Temple”, set amongst huge gingko trees

According to one story, Buddhism arrived at Emei in 63 AD, not long after the religion first reached China from India. A medicinal plant collector named Pugong (蒲公) followed the lotus-shaped hoofprints of a deer right to the mountain’s summit, where he saw a rainbow-coloured apparition of Puxian riding an elephant on the clouds below. He told his friend, the Indian Buddhist monk Baozhang [宝掌], and later built the mountain’s first shrine at the same spot. The rainbow clouds – still seen today – are known as “Buddha’s Halo”.

Sceptics point out that Baozhang lived several hundred years later than this, and that Emei was originally a Daoist retreat. Buddhism probably didn’t arrive here until the fourth century and, along with the Puxian cult, wasn’t firmly established for another five hundred years. Even today, many of Emei’s temples – named after folk gods, dragons, and mythical heroes – reflect Daoist origins, even if they’re staffed by Buddhist monks.

Whichever version is true, Emei has been a major religious site for over fifteen hundred years, attracting countless tourists, poets and pilgrims. By the nineteenth century there were between eighty and a hundred temples on the mountain, home to two thousand monks.

Nineteenth-century temple’s traditional beam and plasterwork construction. Modern renovations tend to use concrete, which is fire-resistant but quickly gets covered in mildew

Despite the heat, midsummer marked the main pilgrimage season when inns at Emei town, at the base of the mountain, would be bursting with foot-hardened wanderers – some of whom had already spent months walking here from eastern China. All departed at dawn for their crack at the peak, toting staffs for their legs and oil-paper umbrellas for the near-certainty of rain. The poorest pilgrims wore simple blue cotton clothes, while richer ones were accompanied by a train of servants lugging their baggage. Chinese women, crippled by bound feet, were carried up in sedan chairs or on the backs of porters. Not all pilgrims were Chinese; Emei was also holy to Tibetans and Sichuan’s Yi ethnic minority (though monks on the mountain despised these “barbarians” and often wouldn’t let them stay in temples).

Leaving Emei town through the southern “Conquering the Peak” gateway, the path to the top was said to be 120 li long (60km; it’s probably closer to 40km). Tougher pilgrims – or those who couldn’t afford more than one night on the mountain – would make the ascent in just one day. It’s wasn’t an easy hike either: the level flagstoned trail soon became an endless, steep, uneven stone staircase where even hardy pilgrims were overtaken by porters with thighs like tree trunks, or orange-robed Buddhist monks, thumbing rosaries as they drifted steadily uphill in straw sandals. There were mules carting supplies and building materials, gangs of aggressive macaque monkeys who robbed hikers by day and sheltered from freezing fogs under monastery eaves, thick clumps of bamboo, giant rhododendrons, groves of conifers, dove trees and gingkoes and – so it was rumoured – plenty of tigers.

As for the weather, one nineteenth-century visitor commented “one can never predict clouds or sunshine, lightning, thunder, hail or snow”. All you can say is that the summit is around 15ºC cooler than the foothills, and so likely to be frozen between October and April.

Mule train on one of the easier stretches of steps

During my time as a guidebook writer I hiked to the summit of Emei at least three times and wrote eight different accounts – going down 40km of stone steps is far worse than climbing up them, and leaves your knees like jelly for days afterwards. While it was easy to record impressions of the mountain, historical information was hard to come by until I found A New Edition of the Mount Omei Illustrated Guide, published in 1936 by an American, Dryden Linsley Phelps.

Cover of 峨山圖志, A New Edition of the Omei Illustrated Guide, 1936

Born in 1892, Phelps (费尔朴, Fei Erpu) hailed from Colorado, and from an early age made hiking expeditions with his father to the Rockies and High Sierra. He took degrees in English and Divinity at Yale, served as a chaplain during WWI (where he was cited three times for bravery and awarded the Silver Star for carrying wounded under heavy fire), and later spent a year on a fellowship at Oxford University.

In 1921 Phelps married Peggy (Margaret) Hallenbeck, and shortly afterwards headed to China with the American Baptist Foreign Mission Society. The couple spent the next thirty years at West China Union University (WCUU) in Chengdu, capital of Sichuan province, Phelps as dean of the College of Arts, Peggy heading the Department of Fine Arts. Teaching included religion, philosophy and English literature; the poet Robert Browning appealed to Phelps’ students because, like their own classical Chinese poets, Browning was “terse, succinct, witty, epigrammatic, unique in a brilliant use of words, profound, a lover of nature, and of human nature, a lover of life.”

Phelps was involved with at least two other books before tackling Mount Emei: The Philosophy of Lao Tze, a translation into English of the Daoist classic Dao De Jing; and collaborating with colleagues translating H. Burton Sharman’s Jesus as Teacher into colloquial Chinese, introducing Christian teachings in “a new format attractive to Chinese taste”.

Team translation of Jesus as Teacher. From left to right: Dryden Phelps, Constance Walmsley, Leslie Earl Willmott, Peggy Phelps, Lewis Walmsley and Katharine Willmott. Katharine Willmott later collaborated with Phelps on Pilgrimage in Poetry to Mount Omei; while Lewis Walmsley donated a set of woodblock prints of Chinese deities to the Royal Ontario Museum, which I wrote about in Paper Horses. Note Phelps’ straw sandals, still an essential part of the hike up Emei in winter, when they grip the icy upper paths securely. Photo by permission of Cory Willmott

Western Sichuan is generously covered in mountains overflowing from the Tibetan Plateau, and Phelps brought his childhood love of climbing with him. During his first year in China he joined an expedition to explore peaks in Danba county, which surveyed 7500m-high Gongga Shan (aka Minya Konka; conquered a decade later by an American team). And at some point, he made the first of many trips to Mount Emei.

Foreigners had already “discovered” Emei. The British diplomat Edward Colborne Baber visited in 1877 and left the earliest account in English of the route to the summit; he was followed over the next decade by Canadian missionary Virgil Hart, and an American named “Mrs Lewis”, apparently the first Western woman to make the ascent. The mountain’s dense forests attracted botanists and naturalists such as Antwerp Edgar Pratt, who made at least two trips in the 1890s, while curiosity drew in several experienced China hands – including Archibald Little (the first person to navigate the Yangtze’s dangerous Three Gorges in a steamship), and Reginald Johnston, tutor to China’s last emperor. By the 1920s Emei’s cool, wooded slopes had even become a popular retreat for university staff during Chengdu’s sweltering summers.

Many of these early Western visitors wrote travelogues of their experiences. Phelps’ contribution would be to translate the Mount Emei Illustrated Handbook (峨山圖說), a Chinese-language guidebook first published in 1891.

Upper paths in fog

The Handbook came to be written by official command. As recorded in the Peking Gazette of 1 September 1885, the Sichuan governor Ding Baozhen (丁寶楨) petitioned the throne because, out of all China’s major holy mountains, only Emei held no annual sacrificial ceremony in honour of the resident deity. At Emei, wrote Ding,

…the charms of nature are to be found in profusion, it bears a world-wide renown, and in the province of Sichuan itself its protecting influence is widely relied upon.

Prayers offered to the mountain in times of flood, drought or pestilence, meet with prompt response, for as it is richly endowed by nature its protecting powers are correspondingly extensive.

The benefits thus bestowed by the mountain have never been recognised by the offer of incense on the part of the local authorities, and considering how dependent the people are upon its influence for the preservation of their existence, the Memorialist considers that it should be included in the list of those to which worship is due, as the neglect of this function by the authorities seems to him to savour of ingratitude.

The emperor Guangxu agreed, and granted Ding’s petition. And so, continues the Handbook’s foreword:

The following year the Hon. Deputy-Viceroy You Zhikai (游智開) sent Mr Huang Shoufu (黄绶芙), the Intendant-elect, to make an investigation of Emei. Upon his arrival he discovered that all the ceremonial spots, monasteries and shrines contained an image of Buddha. But there was no shrine for the mountain deity (山神)… Mr You then contributed money for the erection of a temple at the foot of the mountain in honour of the local divinity.

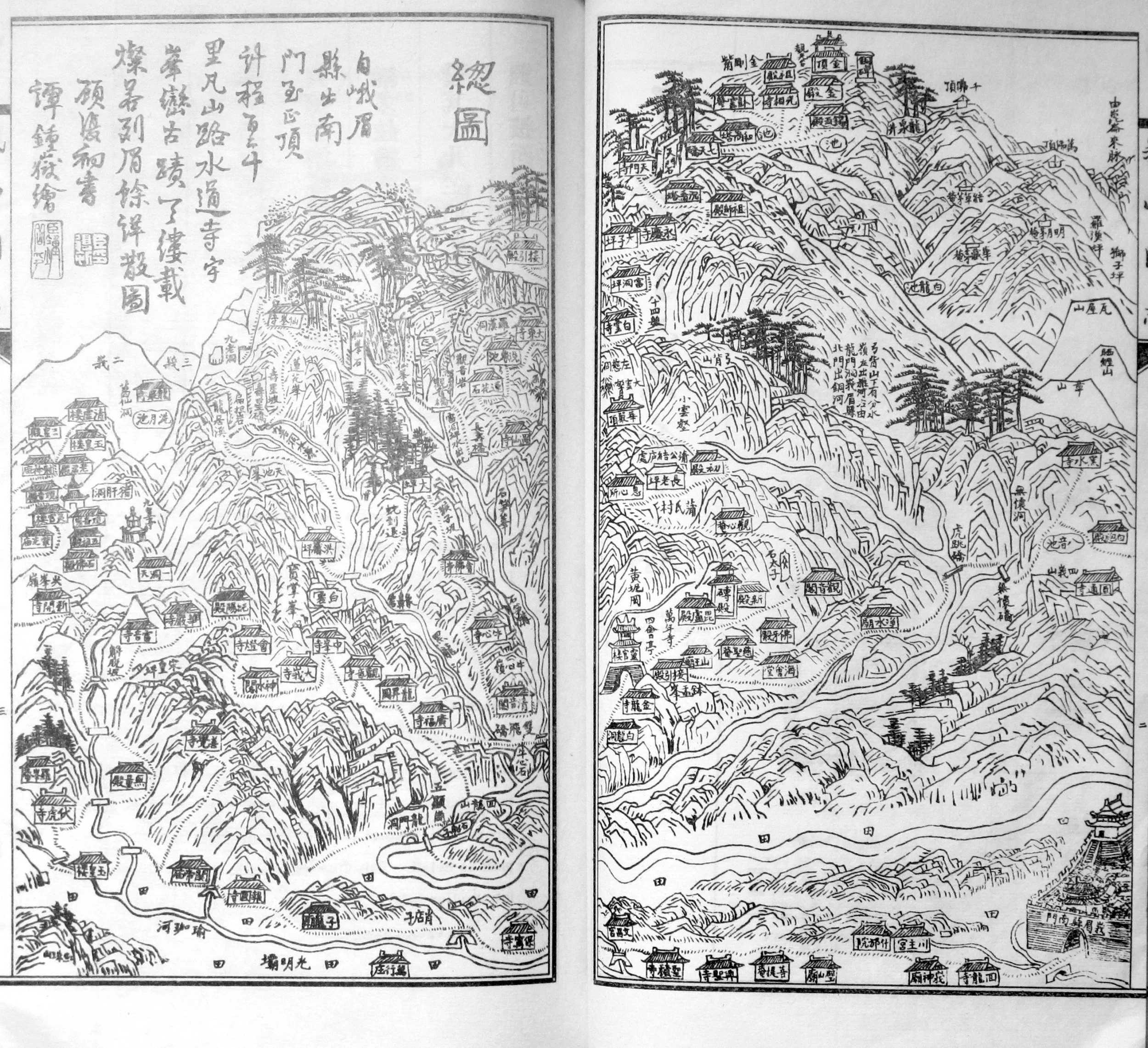

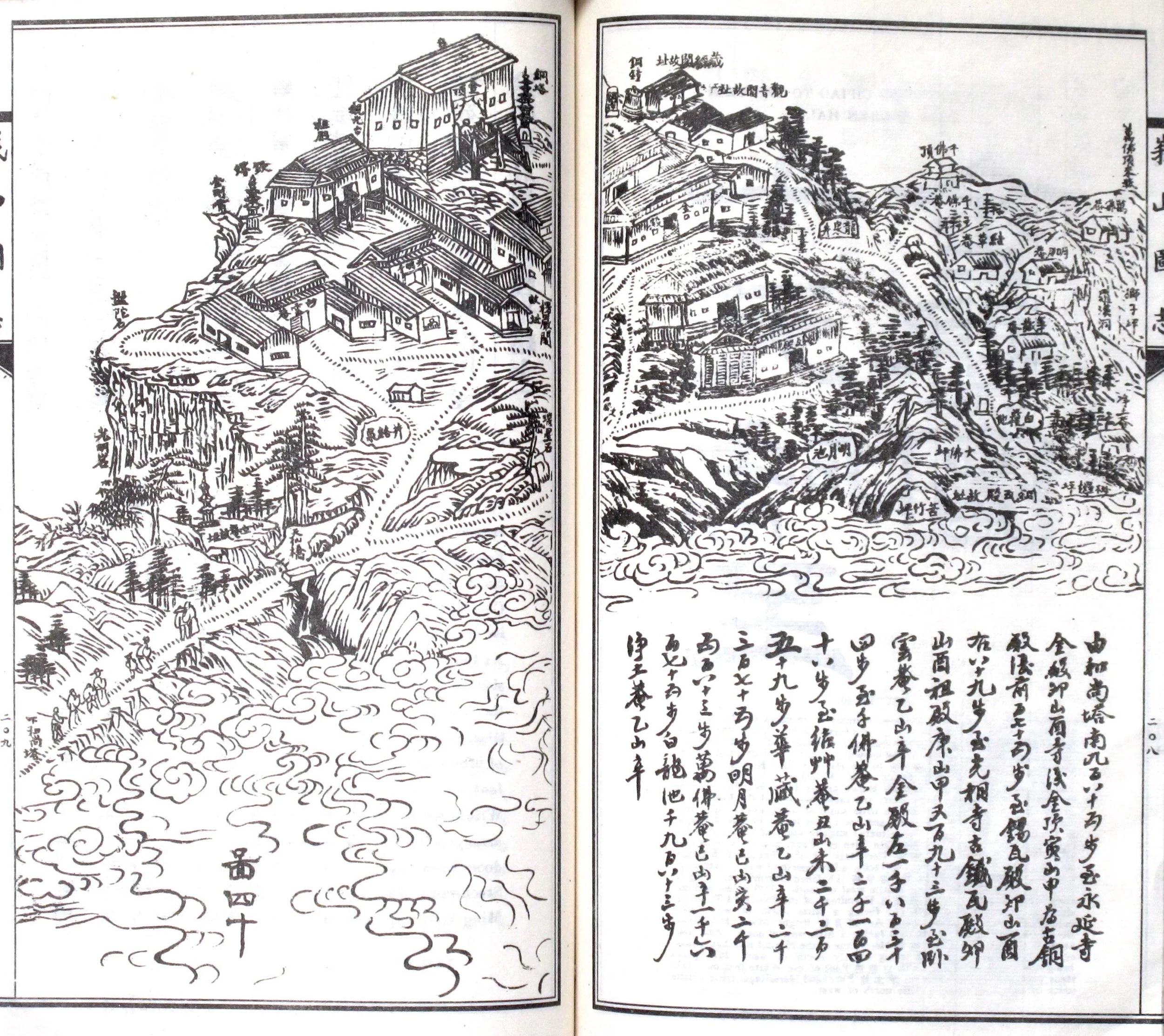

You Zhikai also found that official records of the mountain were incomplete. He commissioned Huang Shoufu and the scholar Liao Shengtang (廖笙堂) to gather information from folklore, personal experience and government documents. Meanwhile, artist and poet Tan Zhongyue (譚鍾嶽, also known as Tan Qingfeng, 譚晴峯) was sent to sketch the mountain’s buildings and scenery first-hand: “So, taking my brush along in its bag, I went, combing my hair with the wind and washing my head with the rain… Several times I met with tigers, who did me no harm… Half a year went by, and the pictures were finished.” Tan produced 53 illustrations of the main temples, with another 11 of famous scenes; he also wrote 46 short poems describing his impressions and experiences.

Temple complex amongst forest and peaks, from the Mount Emei Illustrated Handbook, 1891

Following the main path via Wannian Temple to the peak, the Handbook gave short descriptions of each temple, filling in on the gradient, local legends, views or other useful information. It also covered an alternative mid-level path, and a summary oftwo other peaks in the Emei ranges. After Huang Shoufu died unexpectedly, You Zhikai and the local governor, Huang Xitao (黃錫燾), completed the text. The Mount Emei Illustrated Handbook was finally published in two woodblock-printed volumes in 1891.

And so back to Phelps. He had already become captivated by the mountain, visiting temples and joining pilgrims on several ascents, when David Graham, curator at the university museum, suggested that he wrote a book about Emei’s history. But while researching official records Phelps came across the Handbook, printed over forty years earlier, and decided to translate it into English instead.

Phelps spent over three years on his project, working through the difficult classical Chinese text and poetry with its specialist Buddhist terms (his friend and collaborator Mary Willmott helped translate the verses), learning the complexities of using a Chinese compass, and revisiting Emei many times to make sure he understood the book’s descriptions of landscapes and buildings.

Published in 1936 by the Harvard-Yenching Institute, A New Edition of the Omei Illustrated Guide Book (峨山圖志) was a bilingual, annotated translation of the original Handbook, its 354 pages stitch-bound in the traditional Chinese manner. There were additional new forewords by local scholars and dignitaries – including the abbot of Jieyin temple, Sheng Jin (聖欽, 1869–1964), a farmer’s son who had run off to become a priest aged sixteen – all of whom were impressed by Phelps’ enthusiasm for the mountain.

Because the original woodblocks had been lost, Tan Zhongyue’s illustrations were redrawn for the New Edition by Yu Zidan (俞子丹). All that is known about Yu is that he was a Chinese tutor at the university and a respected calligrapher; he also drew vignettes of daily life in Chengdu, published decades later by William Sewell – another teacher at WCUU – as The Dragon’s Backbone.

A Panoramic View of Emei, from A New Edition of the Omei Illustrated Guide. Emei town is bottom right, showing the gateway at the start of the path. Yu Zidan copied the original woodblocks very faithfully; it’s sometimes hard to tell the difference at a glance

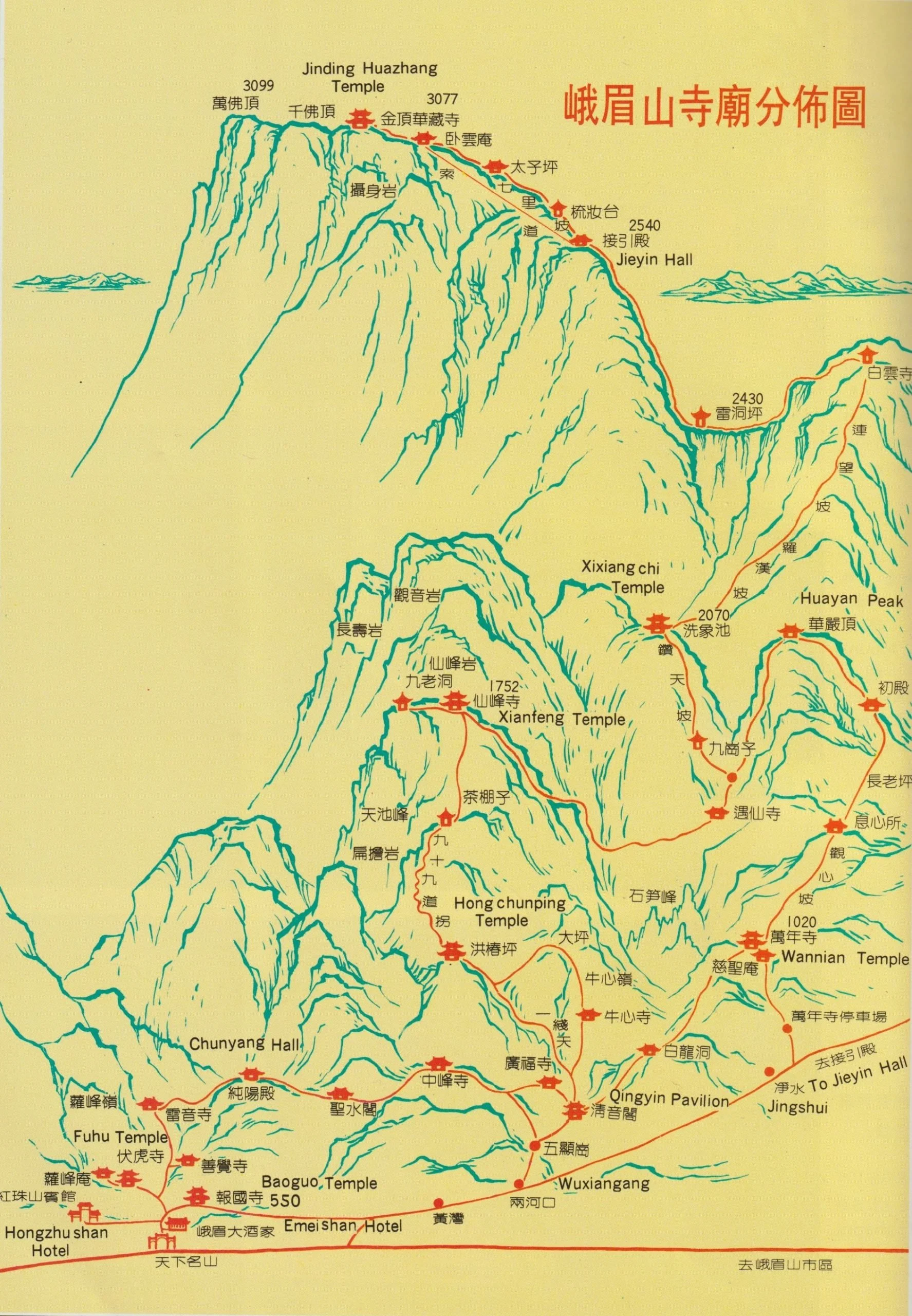

After 35 short introductory poems, the guide kicks off with a Panoramic View of Emei, showing “more than seventy” temples, waterfalls, peaks, cliffs and the stone paths tying everything together. Many buildings – such as the E Shen Temple (峨神廟) built by You Zhikai for the mountain deity, and all the lower temples between Emei town and the mountain – no longer survive. The main temples still standing are covered below, mixing Phelps’ translation with my own research.

Baoguo’s temple bell

Today, the mountain’s gateway is Baoguo Temple (報國寺), founded relatively recently in the early seventeenth century. Despite the number of visitors it’s a calm place whose bell, in a front courtyard tower, can be heard miles away.

Pick of the lower temples include the once-dilapidated Da E Monastery (大峨寺), restored in the late nineteenth century by its abbot, Lao He Shang. A former government official, he became a Buddhist monk after a pilgrimage to Emei and established a wax-making industry at the temple, using the profits to renovate the halls and courtyards.

3m-tall bronze pagoda covered in figurines and the text of the Lotus Sutra, sacred to Puxian. The major figures are Gautama in the centre, flanked by Puxian on his elephant, and Wenshu on his blue lion. Currently housed at Fuhu Temple, near Baoguo

The rugged path beyond here, where “one winds his way about by clasping his staff and climbing by means of the thickets”, eventually descends to the Twin Flying Bridges (雙飛橋). These cross a deep gorge where two streams converge noisily, and you can sit and listen at nearby Qingyin Pavilion. A short detour leads to Niuxin Temple (牛心寺); whose legends of fire demons and immortals practicing alchemy reflect a Daoist heritage.

Most people overnight at Wannian Temple (萬年寺), founded during the Jin dynasty (265–313 AD) and surrounded by tall old trees. Wannian’s main draw is a square brick building housing the life-sized bronze statue of Puxian riding his six-tusked elephant, which dates to the tenth century. Another hall contained a statue of a deity holding a white rabbit, the god of “some of the aboriginal tribes on the western borders of Sichuan, who make repeated pilgrimages to this mountain”.

Song dynasty bronze sculpture of Puxian riding his elephant. Visitors in the nineteenth century reported parts of the trunk, tusks and legs had almost worn through from pilgrims rubbing the statue for good luck. Last time I visited the security fence had been moved further back so that it was impossible to touch the elephant

Overshadowed by tall trees and crags, gradients increase past Wannian with a 700m climb said to be so steep that as you crawl upwards your knees bang into your chest. At the top is Chu Hall(初殿), marking where Pugong found the hoofprints which led him to the summit and his vision of Puxian. From here “disordered hills rise vertically… sidling along, one advances some paces, and then ascending a risky tooth-like staircase, one seems to be climbing to heaven.” The next stop is Xixiang Chi (洗象池), a hexagonal stone-flagged pond where Puxian’s elephant went for a wash. The roof of the temple here is reinforced to cope with heavy winter snowfall.

In a saddle above Xixiang Chi at Leidongping (雷洞坪) sits a mossy, two-storied temple to the thunder god, a folk deity. It’s always gloomy, cloudy and wet here; you have to stay silent or risk attracting violent storms. Then you climb the Eighty-four Bends, through forests of ancient rhododendron and dwarf bamboo, to Jieyin Hall (接引殿). In 1660 a monk saw the image of Buddha here and decided to lie on the path fasting for seven days, despite heavy snow, in order to raise money for a monastery; the provincial governor heard of his devotion and immediately paid for the project. On his 1877 visit Baber met Jieyin’s abbot, who had travelled widely in China and talked about laolin, Emei’s ancient forests, full of tigers, bears and other dangerous creatures. The temple had just been rebuilt after a disastrous fire, and halls nearby housed the mummified bodies of two former monks.

Temples crowding the summit area, from A New Edition of the Omei Illustrated Guide

A final stiff ascent brings footsore pilgrims to the summit area, Jinding (金頂). Of the various temples here, Huazang (華藏寺) covers an acre and occupies the site of Pugong’s original shrine, renamed Huazang – something like “Treasury of Brilliance” – by imperial decree in 1614. A century ago the summit’s temples functioned as commercial enterprises, competing for pilgrims’ custom, arguing over the age and originality of their statues, who had logging rights in the forest, and so on. Nowadays two modern hotels charge extortionate room rates.

Behind Huazang sits Jin Dian, the Golden Hall (金殿). According to the Handbook,“The tiles, pillars, portals, door lintels, window lattice – all were bronze mixed with gold. The height was more than twenty feet, and its depth and width each more than ten feet. Within was a likeness of Puxian. Around the sides were arranged the Ten Thousand Buddhas. On the insides of the doors were engraved mountains, rivers, and roads of all Sichuan… But now it is in ruins”. Baber wrote that the hall had been blown apart by lightning in 1819; others that it had burned down in 1544, 1851 or 1890. Whatever really happened, Jin Dian has since been rebuilt – though the modern incarnation is just an ordinary brick and timber building, painted gold.

Mummified body of a monk, from one of the summit temples. Photo taken 1906–1909, from Old China in Historic Photographs, by Ernst Boerschmann

At the back of the temple a sheer precipice drops 1500m into the clouds, where hundreds gather every dawn to see Buddha’s Halo; everything is chained off for safety but in the old days pilgrims were known to jump over the edge in ecstasy at the sight. Now the railings are encrusted in padlocks, engraved with couples’ names, symbolising eternal love (though I saw one man, cursing bitterly, sawing a padlock off).

In a final nod to Emei’s Daoist roots, characters inscribed on an inaccessible crag opposite the viewing area once read: “The place where Yuyi and Jielin possessed themselves of the Dao, Yuyi becoming a sun deity and Jielin a moon spirit” – in Chinese mythology Yuyi carries the sun across the sky, while Jielin carries the moon.

Buddha’s Halo appearing in the clouds below the summit temples – note the figure apparently jumping over the edge in his eagerness to touch the apparition. The drop is 1500m, nearly half the height of the mountain. Painting by Tan Zhongyue, but not part of his work for the original Mount Emei Illustrated Handbook

Even as Phelps translated the Handbook, the information in it was obsolete. Temples have always come and gone on the mountain – on average, one burns down every seven years. Some are rebuilt, others relocated, neighbouring complexes sometimes merge, and many get abandoned and forgotten about.

About 70 temples were still standing in the 1930s, but the following decades were not kind to the mountain. With the exception of the brick pagoda and its elephant statue, Wannian was destroyed by fire in the 1940s, and by the 1960s most monks on the mountain had been evicted by the communist government, leaving temples to fall into ruin. In the summit area, both Jieyin Hall and Huazang Temple burned down again.

Huazang temple in the fog, c.1998. It has been considerably rebuilt since then

Rebuilding since the 1980s has restored around thirty temples, with the focus on larger, more popular sites. Many people now reach the summit by road and cablecar, saving time and their knees by skipping the stone stairs and many of the mid-mountain temples – which have consequently received less funding and perhaps retain more of Emei’s older character. The most overbuilt new construction is a 48m-high gilded statue of “Puxian of the Ten Directions” which now faces Huazang Temple – seemingly forgetful that the earlier bronze temple here was destroyed by lightning.

Tourist map of the mountain from 1990, showing about 30 temples still functioning

Near-constant warfare plagued Phelps’ time in China, as the Nationalist government and local warlords fought for dominance. WWII saw the Japanese invade too, followed by a resumption of civil war in 1945, and Phelps was still at West China Union University when the victorious communists took control in December 1949. He wrote a letter enthusiastically supporting the new administration to the Reverend William Mellish, a left-wing Brooklyn Episcopalian, who had it printed in the Churchman and a US pictorial magazine, Soviet Russia Today.

Phelps was not alone in being impressed by China’s early communist regime. The Nationalists, in power since the 1920s, were corrupt and self-serving, and had done little to unite the country. Their soldiers were often undisciplined, prone to looting and widely regarded by the wider population as vicious bandits.

In comparison, communist fighters impressed many – including independent foreign observers – with being loyal to their cause, well-trained and unusually honest. According to Martin Johns, who grew up on the WCUU campus in the 1920s, “Whatever one might dislike about the Communists, they were the first governing force in [thirty years] who exercised discipline over its soldiers. A Communist soldier in those days caught looting by his superiors was summarily shot.”

Dryden Phelps with baby panda. According to Cory Willmott, whose grandparents worked with Phelps, “Missionaries played a crucial role in capturing and transferring pandas to North American and European zoos. When a missionary had succeeded in capturing a baby panda, they would live in someone’s backyard on the WCUU campus until their transport was arranged.” Photo by permission of Cory Willmott

Unfortunately, after the Korean War broke out in 1950 Phelps denounced the Western media’s crusade against communism. Given the Cold War paranoia of the time, the American Baptist Foreign Mission Society had little choice but to order Phelps back to the US to explain himself. As reported by Time magazine, he defended his opinions as being based on first-hand observation, rather than political dogma. In return for his resignation the disciplinary board concluded that Phelps was not a communist, and that he and his wife had “always been, and are now, loyal American citizens”.

Phelps settled in California, became pastor of the Church for the Fellowship of All Peoples, and was on the board of The American Academy of Asian Studies. He returned to China with his wife in the early 1970s for a month-long tour, and died in 1977.

In 1983, Katharine Willmott published Pilgrimage in Poetry to Mount Omei, translations of classical poems about Emei which she and Phelps had collaborated on.

Many thanks to Cory Willmott, Professor at the Department of Anthropology, Southern Illinois University, for background on the WCUU and its teachers, and giving permission to use photos of Phelps.

Sources

Baber, E. Colborne Travels and Researches in Western China (John Murray 1882)

Cox, James The Old Priest of Mount Emei (Department of Missionary Literature 1906)

Gan Minfeng Historical Changes to Temples at Emei’s Golden Summit (峨眉山金顶寺庙群的历史变迁, https://thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_17774497)

Graham, David Crockett Religion in Szechuan Province, China (Smithsonian Institution 1928)

Hart, Virgil Western China: A Journey to the Great Buddhist Centre of Mount Omei (Ticknor and Co 1888)

Huang ShoufuandTan Zhongyue An Illustrated Handbook of Mount Emei (峨山图说, 1891)

Johns, Martin Bamboo Sprouts and Maple Buds (MWJ, 2008)

Johnston, Reginald Fleming From Peking to Mandalay (John Murray 1908)

Kendall, Elizabeth Kimball A Wayfarer in China (Houghton Mifflin 1913)

Little, Archibald John Mount Omi and Beyond (William Heinemann 1901)

North China Herald (1885)

Phelps, Linsley Dryden

– A New Edition of the Omei Illustrated Guide Book (峨山图志, Harvard-Yenching Institute 1936)

– with Willmott, Mary Katharine Pilgrimage in Poetry to Mount Omei (Cosmos Books 1983; a selection at http://www.mountainsongs.net/translator_.php?id=33)

Pratt, Antwerp Edgar

– Illustrated London News (25 April 1891)

– To the Snows of Tibet Through China (Longmans Green and Co. 1892)

Studies in Browning and his Circle (Vol 6, no.2, 1978)

Time (4 February 1952)

UNESCO Mount Emei World Heritage listing (https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/779)

Zhang Dezhong Mount Emei (峨眉山, Sichuan People’s Publishing House 1990)