Examples of Confucian Filial Virtue 二十四孝

I recently bought a scroll showing three of the Twenty-Four Examples of Confucian Filial Piety (二十四孝). This collection of parables about children sacrificing their own comforts for the benefit of their parents was first compiled by the fourteenth-century scholar Guo Jujing (郭居敬) after his own father died, and they became a popular subject for folk prints.

These three woodblock prints are possibly from Gaomi (高密) in Shandong province, but similar ones were also made at Yangliuqing, just west of Tianjin, and Taohuawu district in Suzhou. As the panels don’t follow the usual story order (they are #9, #17 and #6) there were probably twenty-four separate blocks which were printed as the customer demanded – so this particular arrangement might be unique.

Guo Jujing took the tales from classical literature, so there are many different reworkings of them. The versions here are from the writings of three nineteenth-century scholars – which suggests that the designs date to the same period.

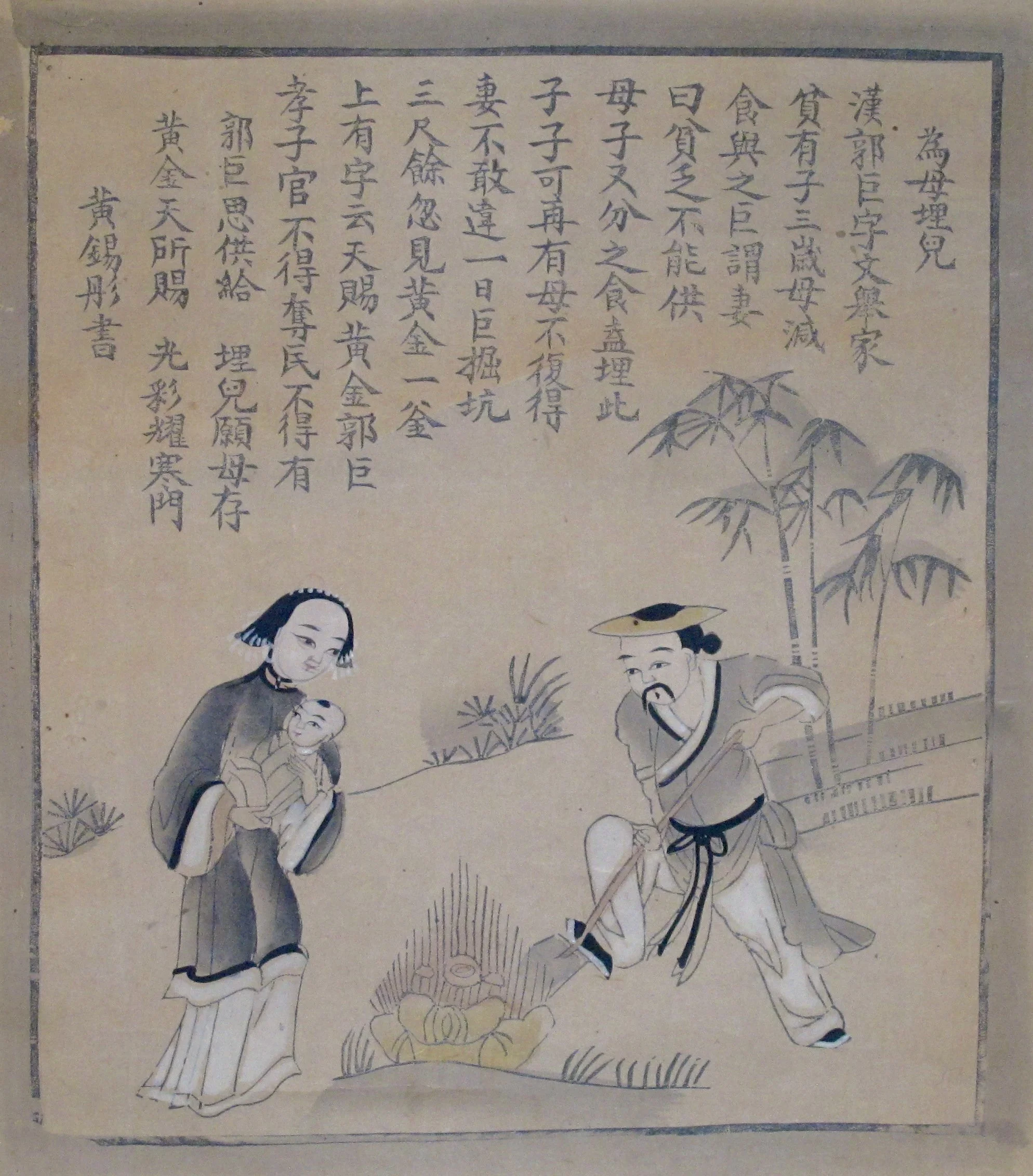

Burying a Son for the Mother (為母埋兒), as told by Huang Xitong (黃錫彤; active from 1850s). Back in the Han dynasty, the impoverished Guo Ju was married with a three-year-old son, and living with his elderly mother. Food became so scarce that Guo Ju told his wife to bury the infant, on the principle that the two of them could have another child, but he could never replace his mother if she starved to death. While digging the pit he unearthed a cauldron full of treasure, inscribed with the words “Heaven Rewards a Filial Son”.

Attracting Mosquitoes to Drink Blood (恣蚊飽血) by Zhu Youran (朱逌然; 1836–1882). The tale of the eight-year-old Wu Meng, whose family was too poor to buy mosquito nets. So he slept outside his parents’ bedroom, allowing the mosquitoes to feed off him and leave his parents alone.

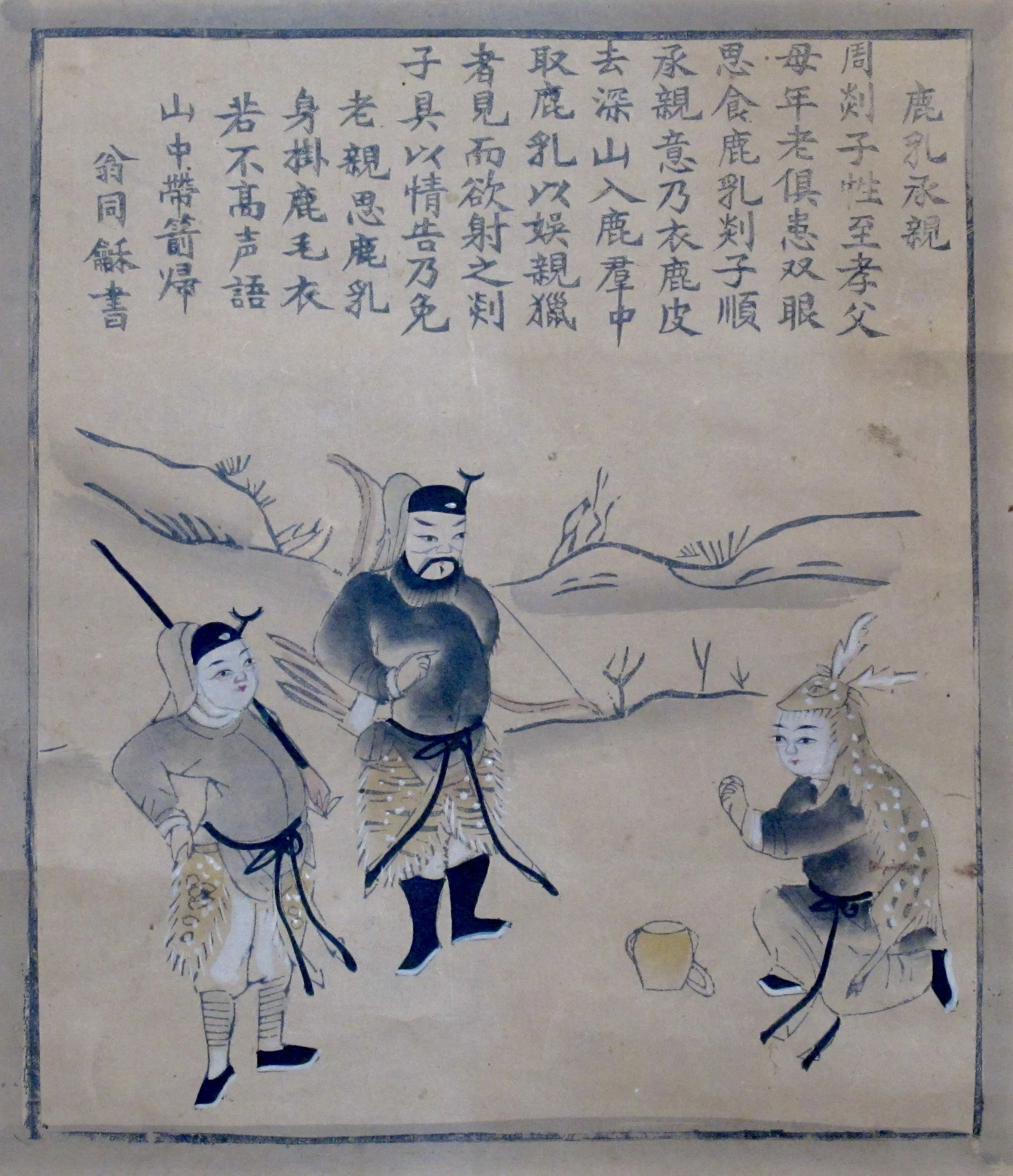

Deer Milk for His Parents (鹿乳奉親), from the writings of Weng Tonghe (翁同龢; 1830–1904). Young master Tan went into the mountains disguised as a deer so he could milk a doe – having been told that doe milk would cure his elderly parents’ failing eyesight. The disguise was so effective that he was nearly shot by two hunters; the text finishes “if he hadn’t called out, he would have returned from the mountains full of arrows”.

I like to think that this scroll might have been put up in the workplace of a wealthy merchant to show that – whatever his customers’ opinion of his business practices – he at least had a few scruples, and respected Confucian morals.