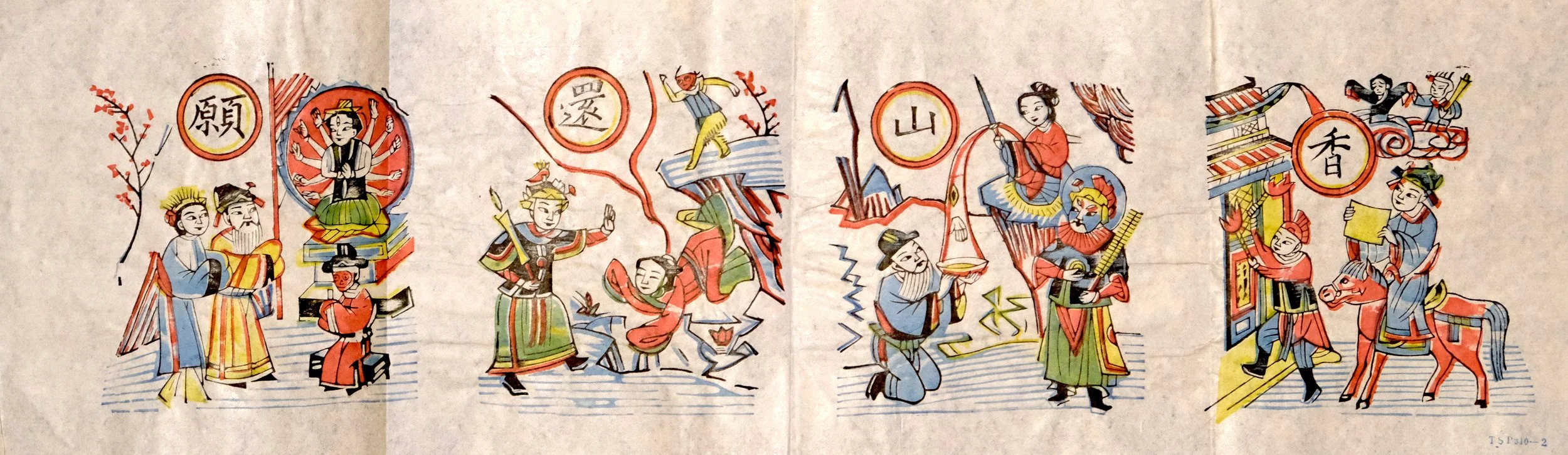

Fulfilling a Vow at Xiangshan 香山還願

Reads right to left, but the scenes from the story are out of sequence

The bodhisattva of Compassion, Guanyin, is China’s version of Avalokitesvera, most likely imported from India – along with Buddhism – during the first century. Originally a male deity, since the Song dynasty (960–1279) Guanyin has usually been depicted as female.

Guanyin appears in many guises. As a gentle figure draped in white robes, accomapnied by two young acolytes and a parrot, she sprinkles calming water over the world and bestows children (or grandchildren) to her female worshipers. This is her most familiar, popular incarnation.

Despite the smiles – coming to burn down the temple

At the other end of things she’s a fierce, multi-faced, thousand-armed deity with eyes in the centre of each palm – a Tantric form derived from Indian or even Tibetan iconography. Each hand holds a weapon or holy object, manifesting an all-conquering power against evil.

This woodblock illustrates an origin tale about one of Guanyin’s less extreme multi-limbed manifestions, set at the Daxiangshan temple outside Miaowan in Shaanxi province (陕西省耀县庙湾镇大香山寺). The complex dates back to the fourth century and sits high on a mountain ridge above the town, with temple halls dotting the summits.

Miaoshan donates her eyes and hands to her father’s envoy, as a martial deity looks on

The story goes that King Zhuang had a daughter named Miaoshan, who despite her marriage wanted to become a Buddhist nun. In the end her father agreed, but only if flowers bloomed in the mountains during winter. Of course they did, and King Zhuang reluctantly had to let Miaoshan enter a nunnery. Later regretting his decision, he had the temple burned down; Miaoshan was rescued by two immortals and fled to a remote cave where she lived as a hermit.

One day King Zhuang contracted a mystery illness, and was told by a wandering monk that only a medicine made from human hands and eyes could save him – as long as these were given willingly. When she heard, Miaoshan “gouged out both her eyes with a knife, then told the envoy to sever her two arms. At that moment the whole mountain shook, and from the sky came a voice commending her: ‘Rare, how rare! She is able to save all beings, and perform impossible acts in this world’”.

Miaoshan falls in the wilderness, as she flees her father’s wrath

The king recovered, found out about his daughter’s sacrifice and went to her cave to beg forgiveness. In the meantime Miaoshan had become an immortal, and Zhuang conferred on her the title “Thousand-Armed and Thousand-Eyed Bodhisattva”. Converting to Buddhism, he had the Daxiangshan temple built in her honour.

Next to genre scenes, these story panels are among my favourite type of woodblock prints. The tale unfolds from right to left: the temple being burned down, Miaoshan donating her hand and eye, Miaoshan roaming the wilderness, and finally the king and queen offering thanks to their deified daughter.

King Zhuang and his wife worship the deified, multi-limbed Miaoshan

The way the figures are drawn resembles those from Wuqiang in Hebei province, but roundels spelling out the title are characteristic of studios at Pingyang, now a suburb of Linfen city (平阳临汾), a famous woodblock-printing centre since the Song dynasty. Feng Jicai’s exhaustive regional print catalogue (中国木版年画集成-平阳卷) identifies it as coming from the Xingchang workshop (兴昌画店).