Miss Fosbery’s Passport

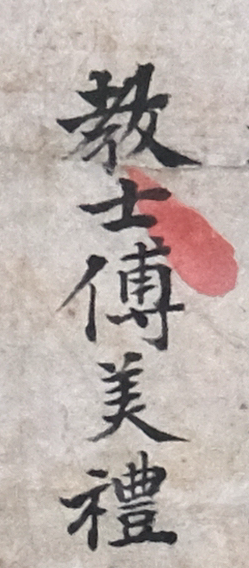

Here’s a Qing-dynasty passport for travel within China issued in 1889 to Miss Emily Fosbery (俌美禮, Fu Meili), a missionary with the London-based China Inland Mission (CIM).

The CIM was founded in 1872 by Hudson Taylor, to recruit missionaries from working class backgrounds and send them to parts of China as yet uncovered by the protestant church. Unlike many other Christian missionaries, CIM members wore Chinese clothing and lived cheaply amongst ordinary Chinese. The point was to show their humility and willingness to fit in, though from a Chinese viewpoint this implied that CIM missionaries were poor, lacked self-respect, and had little to offer converts.

Emily wasn’t a historically important figure, just one of many ordinary people during the nineteenth century who, one way or another, wound up in China; most information about her comes from the CIM’s yearbook, China’s Millions, and census records. She was born in Lambeth in early 1844 to John and Caroline Fosbery; her father was a warehouse worker from Stepney.

Three female CIM missionaries dressed in ordinary Chinese clothing; the embroidery on the middle missionary’s collar reads 那穌救, “Jesus Saves”. Photo by Isabella Bird c.1895; location unknown

In 1861 she was a school assistant at Pilkington in Lancashire, and over the next twenty years appeared in the census as a domestic dressmaker, living in various parts of London. At some point she must have joined the CIM; her address in 1881 wasn’t too far from their headquarters in Hackney.

At any rate, Emily arrived in China as a missionary aboard the Rosetta from London in June 1884. Her first posting was as a Sunday School assistant and nurse at the port of Chefoo (Yantai), Shandong province; then four years later she moved right across China to the Chengdu mission in Sichuan. In 1889 she established a mission school northwest of Chengdu at Kwan Hien (Guanxian, also known today as Dujiangyan), aided by two Norwegian missionaries named Hol and Næss.

Around this time she responded to an “Enquiry into the life-history of Eurasians” for a social-Darwinist-type study by Sir James Cantlie (also a pioneer of first-aid). Asked to detail any special characteristics of mixed-race girls, Emily said they were just as intelligent as any other children, although perhaps with “a greater tendency to lying” – a refreshingly egalitarian view at a time when many people believed that Eurasians were tainted, deteriorated versions of Europeans.

Over the next few years the Guanxian school was well-attended by women and children, though nobody actually converted, and by 1893 Emily was also engaged in “itinerant work” at Maozhou (Mao Xian), between Guanxian and Songpan. Attempts to open another school there were foiled by hostile local authorities.

In 1895, the Guanxian mission baptised their first three converts: a tailor, Mr Sang; U-ting, the mission cook; and a young scholar named Chen. With Emily often absent at Maozhou the mission was now run by a Mr Adam Grainger and his wife, though she later reported that a further ten women from her bible class had converted.

“The Christian Missionary Fu Meili”

By this time China was becoming a more dangerous place for foreigners. Missionaries were particularly targeted, as it was widely believed that their adoption of orphans was really to harvest body parts for medicine. June 1895 saw anti-Christian riots break out at Chengdu during an annual plum-throwing festival, which soon spread to Guanxian. Nobody was killed but church property was ransacked; the local magistrate, Fan Wanxuan, was later removed from office by Imperial decree for failing to suppress the disturbances.

One victim of this xenophobia was the great Victorian traveller and photographer, Isabella Bird, who was stoned by a mob on her journey to Guanxian. Bird stayed at at the mission afterwards to recuperate, reporting the locals as “definitely hostile” and also meeting Emily, though her travelogue To the Yangtze Valley and Beyond doesn’t directly name her: “[The Guanxian mission] had been originally opened to Christian teaching by a lady, who, after living alone there for a considerable time, left for England during my visit [in mid-1896], much regretted.”

At first, Emily’s return home seems to have been for a planned furlough. But in 1898 China’s Millions listed “Miss E. M. Fosbery” – the only record that she had a middle name – as “Home Staff and Undesignated”, so she had probably decided not to return to China. Perhaps increasing aggression against foreigners, with only a handful of converts to show for over a decade’s hard work, had proved too much.

"Her Britannic Majesty's Consulate At Yichang"

Emily next appears on the 1901 British census, visiting friends at Weston-super-Mare. Her age was mistakenly given as 53, and her profession was “retired from China Inland Mission”. An “Emily M. Fosbury” – almost certainly her – died in London in 1905, aged 61.

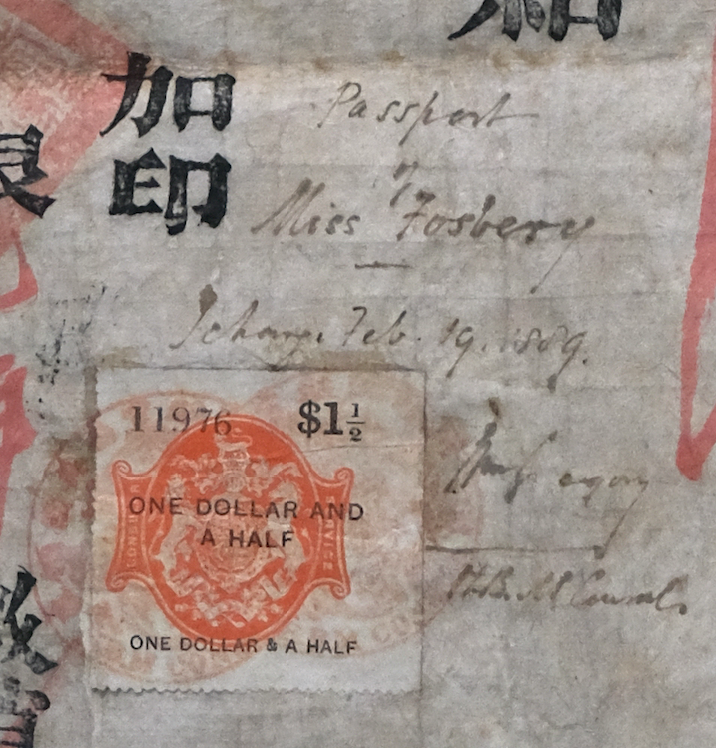

So what about her passport? It’s woodblock printed with specific details filled in by hand, and measures around 50cm x 41cm. It had to be pulled out, unfolded and examined by Chinese officials at every town and customs post along your route, and most passports eventually fell apart from wear. This one is pasted onto a cloth backing to strengthen it, which has helped it survive – they are pretty rare finds today.

The Chinese reads that the passport was issued at Yichang, a small port on the Yangtze river, in accordance with Article Nine of the Treaty of Tianjin (1858), allowing British subjects to travel inside China for pleasure or trade, bearing passports issued by their consuls. The passport had to be surrendered for inspection as requested by the authorities; anyone tampering with their passport, travelling without their passport, or committing some other offense, had to be handed over to the nearest British consul, with minimum mistreatment or restraint.

It is issued to the “British missionary Fu Meili, for travel from Yichang to Hubei, Sichuan and Gansu provinces”; all civil and military personel along her route were asked to treat her with courtesy. The date is given in both Chinese and Western formats – 19 Feb 1889, and 20th day of the first month of the 15th year of the Guangxu reign – possibly when she was on her way to Sichuan for the first time.

The passport is also stamped in red with the seal for “Her Britannic Majesty’s Consulate at Yichang”, and signed “Passport of Miss Fosbery – Ichang, Feb 19, 1889. William Gregory, HBM Consul”, with a receipt attached for $1.5.

(For anyone interested, here’s the full passport text)

護照

大英欽命駐劄宜昌管理本國通商事務頜事官額 為

給發謢照事照得天津條約第九欵內載英國民人淮聽持照前往內地各處遊厯通商執照由頜事官發給由地方官蓋印經過地方如飭交出執照應可隨時呈騐無訛放行僱船僱人裝運行李貨物不得攔阻如其無照中或有訛誤以及有不法情事就近送交頜事官懲辦沿途止可拘禁不可凌虐等雲現據英國教士俌美禮禀秿欲由宜昌前赴湖北四川甘肅遊𢟍請頜護照前來據此本頜事査該人素稱妥練合行發給護照應請.

大清各處地方文武員弁騐照放行務須隨時保衛以禮相待經過闗津局卡幸勿留難阻為此給與䕶照須至䕶照者

右照給俌教士收執

一千八百八十九年二月十九日

光緒十五年正月二十日

大清欽命監督湖北宜昌𨶹荆宜施兵備道