Bishop White’s Falcon

I’ve known this stone rubbing of a falcon forever. My Dad bought it in the 1950s from a gallery in Zürich “because I liked it”, the best reason to buy anything. The shop was near Dad’s business at Pelikanstrasse 6; he thinks it was Orell Füssli at number 10, though they are booksellers and printers, rather than art dealers. (There was also L’Art Ancien SA at Pelikanstrasse 8, who specialised in antique prints and engravings, so who knows.)

Dad has always said the rubbing was Chinese, probably because that’s what the dealer told him. To me it looked Middle-Eastern.

In the wake of investigating some other ink rubbings, I decided to find out more about the falcon. Tineye and Google Images searches turned up results from just two sources, neither of them Middle-Eastern. The first, Chinese Painting (1959) by Peter C. Swann, had a picture of the rubbing (in the same orange as my Dad’s version), but no attribution at all. But the second, older source, Tomb Tile Pictures of Ancient China (1939) by William Charles White, had quite a story.

Bishop William White, aka 怀履光

William Charles White (1873–1960) was born in England, grew up in Canada, and travelled to China in 1897 as an Anglican missionary. He took the Chinese name Huai Lu Guang (怀履光), and in 1910 was consecrated bishop of Kaifeng, Henan province. Here White built a church, founded two secondary schools, became involved in famine relief work as chairman of the Henan Disaster Relief Foundation, and served as chairman of the Kaifeng Red Cross.

White’s interests eventually expanded beyond religion and humanitarian projects, especially after construction began on the Longhai railway through the Yellow River valley in the 1920s. This unearthed a glut of archaeological sites which local farmers and labourers looted, selling their finds to antique dealers in Kaifeng and elsewhere. Noticing the quality of some of these pieces, in 1924 White arranged with Charles Currelly, director of Royal Ontario Museum of Archaeology, to collect antiques for the museum. And so, over the next eight years, White reputedly spent C$90,000 buying over 1100 exceptional bronze and jade artefacts from some recently-discovered tombs in the vicinity of Jincun (金村).

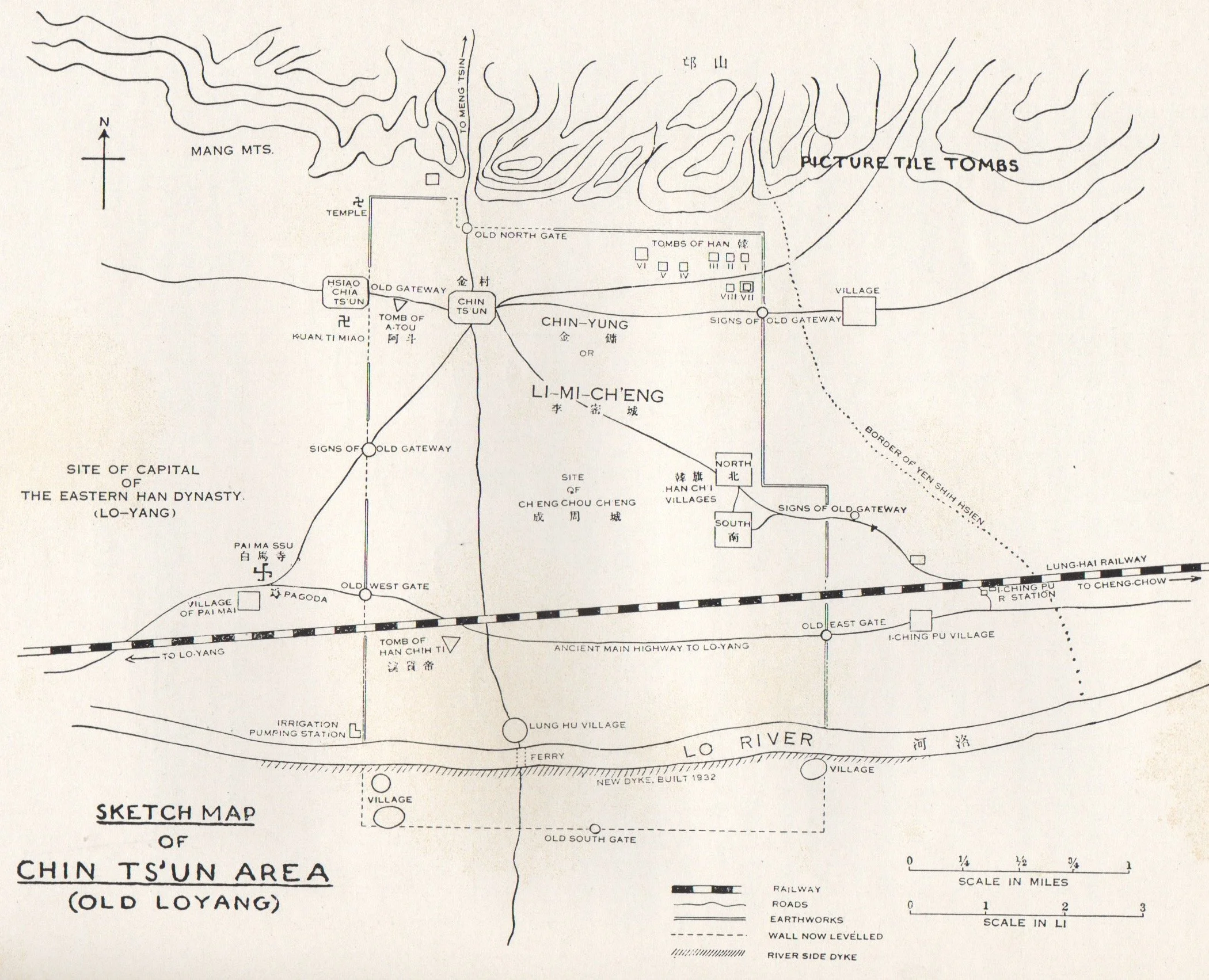

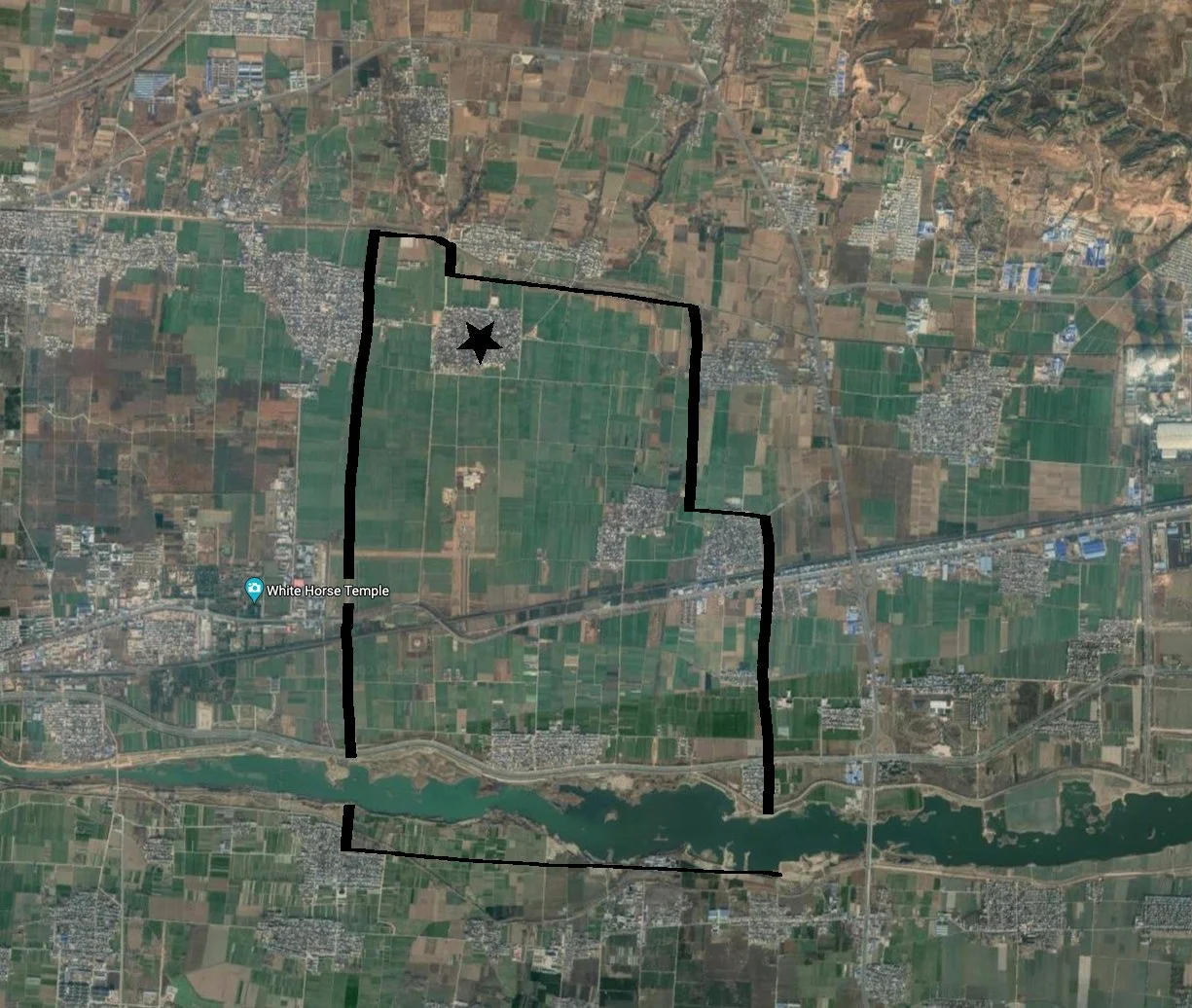

Today Jincun is a small village about 15km east-northeast of modern Luoyang; surrounded by flat fields, there’s a low ridge of worn hills to the north and the Luo River to the south. But the village sits inside the historic boundaries of old Luoyang, an ancient city which has almost entirely vanished (except for the nearby Baima Si, one of China’s oldest Buddhist temples, which was once just outside old Luoyang’s western walls). The finds sold to White date from the Eastern Zhou (c. 500 BC), when old Luoyang was the dynastic capital.

Map of Old Luoyang area, showing Jincun (Chin Tsun) and tombs. “Pai Ma Ssu” and the swastika on the left mark the Buddhist temple

There were other tombs around Jincun too, rectangular, block-lined chambers covered in hillocks which White dated to the late Warring States period (c. 250 BC). Here, looters carted off the tomb walls themselves, which were imprinted with lively hunting scenes featuring archers on foot and horseback, pointing dogs, running deer, hares, birds, leopards and tigers. White bought around sixty of these decorated blocks, which along with the Eastern Zhou grave goods are now in the Royal Ontario Museum (ROM).

The blocks – also described as bricks or tiles – are mostly hollow, rectangular and measure some 165.5cm x 53cm x 17cm. Tombs were constructed two blocks long, one block wide, and two blocks high, forming a chamber around 3.3m x 2m x 106cm.

Plate XXVIII from "Tomb Tiles Pictures of Ancient China" – falcons top right

The decorations were hand-stamped into the damp clay blocks using engraved dies, so that images are often repeated. And one of these blocks – plate XXVIII in Tomb Tile Pictures of Ancient China – has three falcons stamped in a row, one of which has been enlarged and reproduced on its own as plate CIX. This plate CIX is identical to my Dad’s picture from Zürich, and also the plate in Swann’s book, Chinese Painting.

Three rubbings, left to right: from "Chinese Painting" by Swann; my Dad’s; plate CIX from "Tomb Tiles of Ancient China"

Close cross-checking at this point shows that “identical” in this case doesn’t mean all three are exactly the same – but they are all rubbings from just one original engraving. These rubbings are made by laying a damp sheet of paper over the engraved stone block; the paper sinks into any lines and when you dab its surface lightly with ink, these sunken areas stay white. And my Dad’s picture definitely looks right, as you can see where the paper has been heavily embossed by the rubbing process, not to mention the “dabbing” effect in the background.

However, scaling up the photograph of the original tomb block to its full size and taking measurements of the falcons, you get a wingtip-to-wingtip distance of 13cm. The same measurement on my Dad’s picture is 21cm. There’s no way his picture was made from the original tomb block, as illustrated in White’s book. But intriguingly, it is close to the measurements of the rubbing given in Swann’s book (approx 23.5cm x 22cm).

And, as mentioned above, plate CIX, Swann’s version, and my Dad’s rubbing are clearly from the same source. But none of them match any of the three falcons on the original block. So, there are two solutions: either there is another, larger falcon engraving somewhere; or CIX is itself a doctored rubbing based on one of the falcons, with missing bits painted in by hand to create a “perfect” image. And if CIX is a composite, the other two must have been reproduced from this plate, not the block.

So, all I can say is that the Zürich falcon is a real rubbing, but apparently too big and too perfect to be from the tomb block in the Royal Ontario Museum. If I’ve got my measurements correct, and if there isn’t another “missing” Chinese falcon engraving out there somewhere from which it was taken, who on earth went to so much trouble, presumably by photographing plate CIX, etching the enlarged design into a metal plate, and then making an authentic-looking rubbing from it?

Goolge-eye view of Old Luoyang today, with line of old city walls drawn in (badly); the black star marks Jincun

From 1930 it became illegal to export ancient Chinese artefacts. As White continued to do so, he gets bad press in China today as an unprincipled pirate who stole important cultural objects and “threatened and lured the local villagers to help him dig the tomb”. In all fairness, White was only one of many foreign collectors taking advantage of China’s chaotic political situation at the time, with the full connivance of local authorities – who took their own cut of the finds. (The central Guomindang government had only a very loose control over the country, which was in the hands of regional warlords doing pretty much as they liked).

Far from bullying people to dig for him – and despite providing detailed accounts of the site in his Tombs of old Lo-yang (1934) – it seems likely that, at best, White only once visited the excavations at Jincun himself. Instead he gathered as much information as he could from eye-witnesses, including some of the peasant excavators. He didn’t necessarily believe everything that dealers told him about provenance either, though it’s likely several antiques from elsewhere were sold to White as Jincun relics.

But it is true that White, in his enthusiasm to buy what he recognized as a unique trove of artefacts, encouraged the undisciplined ransacking of the Jincun tombs. Now that the finds are dispersed and the in-situ archeaology destroyed, it’s impossible to understand their original context, and what this could have told us about the times.

White returned to Canada 1934, taught Chinese archeology at Toronto University, published books about the Jincun finds and Kaifeng’s relict Jewish population, and became first director of the Royal Ontario Museum’s Far East Collection.

What was left behind at Jincun was re-excavated in 1999. It is now believed that the tombs date to the Han dynasty (202 BC–220 AD).

Many thanks to Gwendoline Adams of the ROM Asian Collection, Clare Newbolt, and Giovanna Stumpo. And, especially, my father Bert Leffman.

SOURCES

bdcconline.net

Chen Shen and Irwin, Sara A Question of Provenance: The Bishop William White ‘Jincun’ Collection in the Royal Ontario Museum (Orientations 47(3):34-41)

Royal Ontario Museum rom.on.ca

Swann, Peter Chinese Painting (1959)

thepaper.cn

White, William Tomb Tile Pictures of Ancient China (University of Toronto Press, 1939)