Six Prints from Taohuawu Studios

Here’s a set of six prints showing scenes from Chinese folklore and late nineteenth-century street life, which originally appeared c1876–1910. They are attributed to studios at Taohuawu (桃花坞), a northern suburb of Suzhou which became famous during the eighteenth century for its skilled and innovative printing workshops. But during the Taiping Uprising (1850–1864) Suzhou was ransacked, first by the rebels and then by Imperial forces; workshops were destroyed and the artists who survived mostly relocated to Shanghai. Older editions of these prints include text stating that they were made at Shangyang (上洋), another name for Shanghai.

A few studios returned to Suzhou in the early 1950s, and my set of six prints dates from after this point, perhaps made as recently as the 1980s.

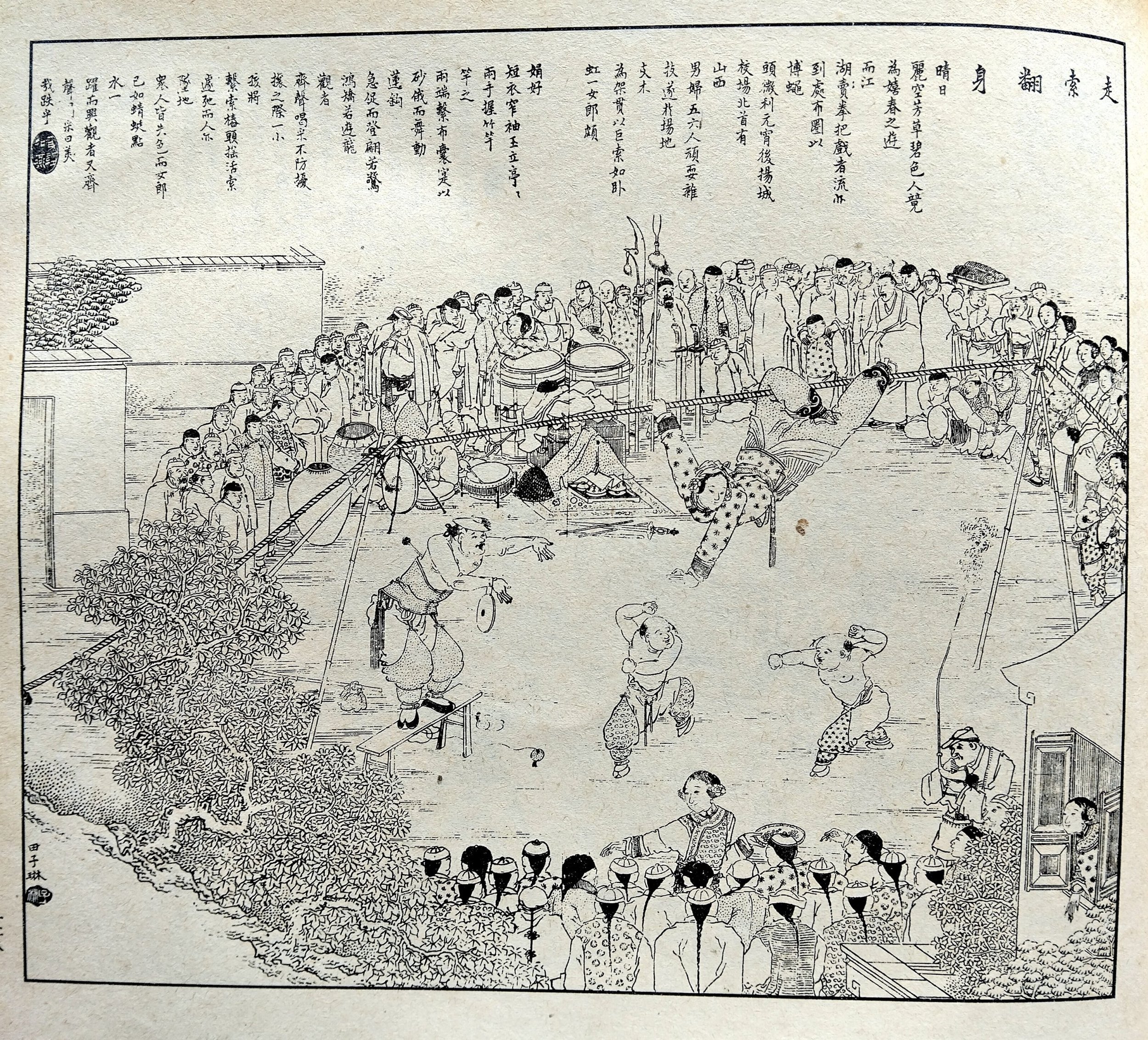

Acrobats Performing in the Yuyuan Gardens, Shanghai 豫園把戲圖

Spectators watch a performance by street acrobats at Shanghai’s Yuyuan Gardens, where a boat ride on the lake is about to depart. The teahouse buildings out over the water top left are still there today, rumoured to have inspired the pavilion on “Willow Pattern” tableware, produced in Britain from the eighteenth century.

Original edition from c1890 naming Wu Youru as artist (left of the title) and Wenyi Studio at Shangyang as publisher (vertically along lower right side)

Original versions of this print state that it was designed by Wu Youru (吴友如; early 1840s–1893) and published by Wenyi Studio (文儀齋). There’s not much solid information about Wu, but as few woodblock artists are known by name, the fact that there is any biographical detail at all is unusual. He was born at Suzhou, and at some point during the Taiping Uprising moved to Shanghai, where he worked both as a traditional painter and in China’s emerging lithographic industry. From 1884 Wu drew pictures for the Dianshizhai Pictorial (點石齋畫報), China’s first illustrated journal, and later founded a rival publication, the Feiyingge Pictorial (飛影阁畫報).

Similar illustration of performers in a park, from Dianshizhai, 1884. I don’t know whether Wu Yourou was the artist

Capturing Lady Jiuhua at Charming Hall 迷人館捉拿九花娘

An episode from the nineteenth-century novel “Cases of Justice Peng” (彭公案 – online in Chinese here ). These gong’an tales became popular during the late Qing period, always featuring an incorruptible magistrate and his loyal lieutenants who solve criminal cases and uncover plots against the nation. For a taste in English try Dee Goong An, aka Celebrated Cases of Judge Dee, translated by Robert van Gulik (who went on to write his own series of Judge Dee novels based on Chinese tales).

Lady Jiuhua is from a bandit family, though the heroes ridicule her as a simple prostitute. She’s first encountered at Charming Hall by Ouyang De, whom she defeats, and later tries to seduce Wu Jie. But he overpowers her, ties her up and takes her to the local magistrate – who, unknown to Wu Jie, is Lady Jiuhua’s lover.

The print conflates several episodes from the tale. On the left, balancing on a chair, is Liu Fang (劉芳), one of Magistrate Peng’s trusted lieutenants. On the left in front of the bed is “Little Fang Shuo” Ouyang De (小方朔歐陽德), an eccentric hero who rides a wooden donkey and dresses in strange clothes, but is also a sincere upholder of justice, skilled in medicine and magic. To the right of the bed is Lady Jiuhua being challenged by twin-bladed “Little Scorpion” Wu Jie (小蝎子武杰), a fierce and determined martial artist trained by Ouyang De.

The swordsman doing a handstand on the chair is He Lutong (來薦子何路通), who appears elsewhere in the novel, while various other characters launch themselves through the air. The character on the bed is possibly the drugged Xu Guangzhi, another hero whom Lady Jiuhua attempts to seduce.

Meng Huo Captured Seven Times at Silvermine Cave 銀坑洞七擒孟獲

A scene from Romance of the Three Kingdoms, the sixteenth-century historical novel about China’s fragmentation into competing states following the collapse of the Han dynasty in 220AD. In chapters 87–90 the master strategist Zhuge Liang is defending his subtropical southern borders against the Man, a primitive warlike people who ride elephants into battle and summon tigers and panthers to fight on their behalf. But Zhuge Liang consistently defeats the Man leader, Meng Huo, who nonetheless refuses to submit until he has been captured seven times.

Here Meng Huo is being defeated for the sixth time, after Zhuge Liang unleashes mechanical creatures to battle the wild beasts fighting for the Man. Zhuge sits under a canopied carriage on the left surrounded by his generals and cavalry; the Man flee right, Meng Huo astride a yellow horse riding out of the frame, his generals the Dailai Cavern King and the Mulu King about to be overwhelmed top right.

In earlier versions of this print the shocking pink dye used here is far paler.

Emperor Yang of Sui Travels South of the Yangzi 隋煬帝下江南

Yang Guang (569–618), last ruler of the short-lived Sui dynasty, initiated vast construction projects (using forced labour), invaded Vietnam and Korea with disastrous results, bankrupted the treasury, and after fourteen years in power was assassinated during a military coup.

The Grand Canal was one of his schemes and at least had a practical use, a thousand miles of channels linking together five river systems between northern and southern China, greatly improving communication, trade and famine relief. It also allowed the luxury-loving emperor to make several trips to Jiang Nan, the rich, cultured lands south of the Yangzi river.

Wearing a yellow robe and long beard, Yang Guang sits amidst ministers and wives in the middle of his dragon vehicle, unaware that the women pulling it have just tripped up and are tumbling over each other. Scholars and young men of leisure look on, accompanied by courtesans (no respectable woman would appear in public), and one red-bearded foreigner dressed in strange polka-dot yellow robes and waving a sword.

“Xincai” Zhaojun Horse Race 新彩昭君跑馬

Another print featuring Emperor Yang Guang, here enjoying the moonlight spectacle of his harem racing around on horseback as they recreate an episode from the famous legend of Wang Zhaojun. Zhaojun was born around 50 BC and, being beautiful and accomplished in the arts, was selected as an Imperial concubine. But she refused to bribe the court painter, who produced a very unflattering portrait of her; as a result Zhaojun was never chosen to visit the emperor.

In 33 BC, China wanted to halt raids from the north by the Xiongnu, and so invited their leader to court. His condition for a treaty was being given a noblewoman to marry. The emperor decided to donate his ugliest concubine, but when Zhaojun appeared in person he realised that he had been deceived. Not one to go back on his word, he allowed Zhaojun’s betrothal to the Xiongnu leader to go ahead – and then had the court artist executed.

The image of Zhaojun on horseback, mournfully playing a lute as she set off for lands beyond China’s northern frontiers, inspired countless dramas and paintings – and these night revels of Yang Guang.

Xincai, “New Colours”, is a porcelain overglaze technique which first appeared in China during the late nineteenth century. It’s possible that this print echoed the style or colours of xincai designs – or that there’s some other meaning here that I’m not aware of.

Earlier editions of this print have the seal and name of Wang Rongxing workshop (王榮興). Wang Rongxing was founded at some point in the nineteenth century, and was one of the studios which set up again at Taohuawu in the 1950s.

Suzhou Railway Steam Locomotive Company Heading to Wusong 蘇州鐵路火輪車公司開往吳淞

This print almost certainly celebrates the opening in 1905 of the Nanjing–Suzhou–Shanghai railway, though the line terminated at Shanghai North station, not the port of Wusong. The line’s history is very convoluted, however, and if anyone out there can correct me on this, please do.

Aside from the train, a group of traditionally-robed Chinese lower left are taking in several other foreign innovations: rickshaws (from Japan), gas lighting, the station’s architecture, a four-wheeled carriage (a forerunner of the motor car), and Western clothing being worn by the couple promenading under an umbrella. Note too the Sikh guard in his turban and red jacket. The Chinese text above the roof gives the train’s daily schedule.

As often happened with Chinese woodblock prints, this one is repurposed from an earlier design celebrating the opening in 1876 of China’s first ever passenger railway, which ran for fifteen kilometres between Shanghai and Wusong. The line was contentious: Shanghai’s Chinese administration was concerned that the British, who had already taken and settled an area north of the old Chinese city, would use the line as an excuse to extend their authority. Within months the railway had been closed, and the track and rolling stock shipped overseas for use in Taiwan’s coal mines.

The original 1876 version – identical except for the title “The Shanghai Steam Railway Company Heading to Wusong”