The Mianzhu Woodblock Rubbing Mystery

Here are some ink rubbings, apparently taken from engraved stone tablets. They show the military wealth god Zhao Gongming riding his tiger, the demon-catcher Zhong Kui, a series of narrow pictures of old men in romantic landscapes, the longevity deity Shou Lao on a deer, and a young nobleman on horseback returning from a successful hunt.

On the left (永鎮家宅) is a typically ugly, fierce image of Zhong Kui with bat and sword; the qin (Chinese zither) slung across his back reflects his cultured achievements. On the right (趙公鎮宅) is Zhao Gongming and his tiger protecting a clutch of chicks; this is based on a nineteenth-century painting in the Mianzhu woodblock museum. The Chinese characters 鎮(家)宅 identify the two rubbings as protective talismans for the home.

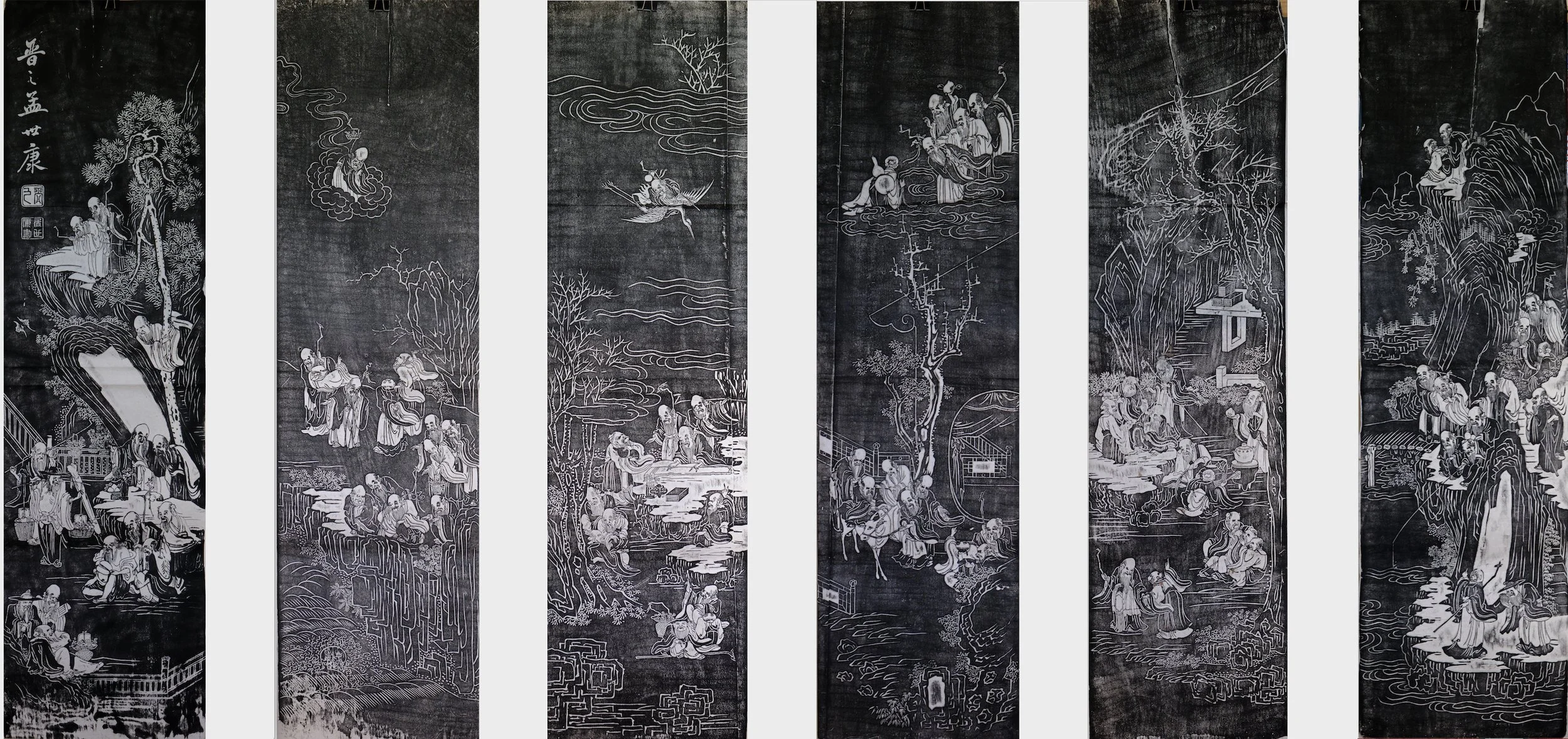

One Hundred Old Men, or One Hundred Immortals, 百壽圖/百仙圖. Six out of a set of eight; from the left, numbers 2 & 3 are missing. Signed by the nineteenth-century artist Meng Shikang (孟世康), about whom almost nothing is known. All these rubbings show age-related damage to the original blocks.

On the left “Long-lived as Heaven, with Plentiful Emoluments” (壽天百祿). “Deer” in Chinese sounds similar to the word for an official’s salary, hence is a stand-in for wealth and position; the peach represents longevity; and the pomegranate the boy is holding represents abundant offspring. On the right, “A Prosperous Promotion” (得祿榮陞). Again, the deer across the rear servant’s shoulders is wordplay for “Official’s Salary”, while the books hanging from the carrypole reflect deep learning. “On horseback” coloquially means “coming quickly”. Both blocks marked 綿邑雲鶴齋發, ”Published by the Yunhe Studio, Mianyi”.

But are they what they seem? Engraving stone tablets with the calligraphy and paintings of famous artists has a long history in China, passing down their work to future generations in a lasting way. To make a rubbing, paper is laid over the face of the engraving, dampened and tamped down so that it sinks into the design, before a cloth bag of paint powder (usually black) is banged and stamped all over, blackening the paper’s surface but leaving the sunken parts white. Peel the paper away, and you have your copy.

At the Beilin Museum, Xi’an. First stage of making a rubbing: overlaying the stone tablet with a paper layer. The artist is using a fine brush to press the damp paper into all the engraved areas. The fan is to dry out the paper once this tamping process is complete.

And yet these rubbings were taken from wooden blocks, not stone tablets, a favoured technique of woodblock-printing workshops at Mianzhu, a small market town about 80km north of Chengdu in Sichuan. Mianzhu’s New Year Woodblock Printing Museum (绵竹年画博物馆) has a good selection of these rubbings, along with recently-recut versions of the wooden blocks.

Modern rubbing block in the Mianzhu New Year Print Museum. Although it does show some chisel marks, I suspect that the block has been cut largely by laser.

My rubbings – bought from the shop Mountain Folkcraft in Hong Kong, who acquired them in the pre-earthquake 1990s – include the two half-sized examples of Zhong Kui and Zhao Gongming, probably from blocks cut in the late 1980s. The rest are modern rubbings from large (over a metre tall) nineteenth-century blocks, several of which show age-related damage. The Hong Kong Baptist University Library, which has a collection of these recent rubbings, suggests that they are the work of Mianzhu master printmaker Chen Xuezhang (陳學彰, born 1947) and his son Chen Jian (陳建, born 1970, who also worked with another master, Zhang Xianfu 张先富).

During the Cultural Revolution, Chen Xuezhang managed to buy up eighteen old rubbing blocks, claiming he wanted them as firewood, before repairing and hiding them away until China’s early 1980s reforms. Three of them were later destroyed in the terrible 2008 earthquake which demolished most of Mianzhu town.

I had a moment of doubt that mine were not rubbings at all but actual woodblock prints, made in homage to the originals. However, a quick look at the back and a feel of the paper showed up the heavy embossing typical of the rubbing process. Unless deliberately blind-stamped, woodblock prints never show such tangible embossing.

Frankenstein flash to capture how the paper has been embossed by the rubbing process

There’s a bit of a mystery behind all this. A skilled printer can run off ten or more monochrome woodblock prints a minute – I’ve seen them do it – but making a large rubbing is a lengthy job, taking several hours. So if you had your design cut into a woodblock, why not just print from it quickly instead of resorting to such a slow, cumbersome method?

When I visited Mianzhu in 2025 nobody could answer this question. According to woodblock historian Jiang Yanwen, there is no record of why this technique was used, and he felt it could simply be down to printing workshops liking the distinctive effect.

With thanks to Jiang Yanwen

References

Chinese Woodblock New Year Study Centre (中国木版年画研究中心), www.nianhua.org.cn

Gao Wen, Wu Shiwu Mianzhu New Year Pictures (绵竹年画; Cultural Relics Publishing House 1990)

Wang Shucun Ancient Chinese Woodblock New Year Prints (Foreign Languages Press 1985)